Biography of John and Audrey Jones Beck

Audrey Beck turned part of her family’s land along Buffalo Bayou into the John A. and Audrey Jones Beck Collection at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH). Her great-grandfather Martin Tilford (M. T.) Jones bought five thousand acres along the bayou in the 1880s to graze cattle and grow grain. The land passed through the generations to Audrey, who acquired it after it was surrounded by the Port of Houston. She sold it piece by piece and used the proceeds to acquire the paintings that grace the Museum’s walls and Houston today.

M. T. and his wife, Louisa Woolard, were the first members of the Jones family to move to Texas from Tennessee. M. T. amassed timberland in East Texas, built sawmills to refine the trees, and owned lumberyards throughout the state to sell the finished products. M. T. and Louisa had three children, including Will Jones, who married Mary Gibbs in 1893. The Jones family grew as other relatives followed them to Texas, including their nephew Jesse Holman Jones.

Fig. 1. Audrey Louise Jones and her great-grandmother Louisa Jones. Courtesy of Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University.

M. T. and Louisa helped develop early Houston. They were founding members of the DePelchin Faith Home for orphans (now the DePelchin Children’s Center) and St. Paul’s United Methodist Church, and they demonstrated to their family the importance of simultaneously building a community and a business: if one thrived, the other prospered. When Jesse Jones arrived in Houston in 1898 at the age of twenty-four to manage the estate of his uncle M. T. Jones, he embraced that approach—and so would his cousin Audrey (fig. 1).1

Audrey had a complicated ancestry. She was born on March 27, 1922, to Audrey Thompson and Tilford Jones, the son of Mary Gibbs and Will Jones. Will was M. T. and Louisa Jones’s son and Jesse Jones’s first cousin. Although divorce was scandalous at the time, Mary and Will divorced in 1919 following a bad marriage and during an unrealized but strong attraction between Mary and Jesse. The eager couple married in 1920, one year after Mary’s divorce from Will. Jesse Jones owned the Houston Chronicle, and his newspaper buried the story about their wedding on a back page in one paragraph; his rival Houston Post blasted the news on the front page with one of three headlines that read, “The Family Won’t Discuss It.” When Audrey was born two years later, Mary became Audrey’s biological grandmother and Jesse her third cousin. Even so, Audrey claimed she had two sets of parents: Audrey and Tilford and Jesse and Mary. Jesse and Mary embraced Audrey as though she was the child they never had. She lived with them more often than with her parents. From the time she could speak, she mispronounced their names, and for the rest of their lives Audrey called Jesse “Bods” and Mary “Muna.”2 They touched her life in many ways.

Audrey grew up at Deepwater—the family ranch near the Port of Houston—in a home on San Jacinto Street in today’s Midtown, and at Jesse and Mary Gibbs Jones’s Lamar Hotel penthouse apartment in downtown Houston at Main and McKinney Streets. During Audrey’s childhood, Jesse Jones, known as “Mr. Houston” to everyone outside the family, built the city’s tallest office towers, its most lavish hotels (including the Lamar), and its most ornate movie theaters. He raised Houston’s half of the funds to dredge the Houston Ship Channel and develop the Port of Houston and served as the Harbor Board’s first chairman. Audrey recalled that people constantly acknowledged her grandfather while she walked down bustling Main Street with him, but she was just as impressed when he knew the names of the panhandlers on the street and the names of their dogs, too. Audrey adopted his openness to everyone.

Fig. 2. Audrey Louise Jones with her grandparents Jesse H. (“Bods”) and Mary Gibbs (“Muna”) Jones at Audrey’s graduation from The Kinkaid School. Courtesy of Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University.

The Joneses were devoted to Audrey. Despite spreading turmoil, European travel was still safe in the summer of 1938 when Audrey and a group of friends headed to England and France with chaperones after school let out. Instead of traveling to the western United States as planned for a vacation, the Joneses set sail on the Normandy to stay close to their granddaughter while she was in Europe. This trip had an enormous impact on Audrey. She recalled in a previous Beck Collection catalogue, “My romance with Impressionism began when I first visited Europe at the age of sixteen as a student tourist, complete with camera to record my trip. I paid homage to the Mona Lisa and the Venus de Milo, but the imaginative and colorful Impressionist paintings came as a total surprise.” She continued, “Works by these avant-garde artists, who had rebelled against the academic tradition of the day, were scarce in American museums at that time. For me, they were not only the epitome of artistic freedom, but also a visual delight. I returned home with many . . . museum reproductions.”3

After graduating from the Kinkaid School in 1939, Audrey attended Mount Vernon College in Washington, D.C., where Jesse Jones was chairman of the federal government’s Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC), the massive agency that had stabilized and expanded the economy during the Great Depression and would militarize industry in time to win World War II. Next to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Jones was reputedly the most powerful person in the nation. Audrey occasionally visited the Roosevelts at the White House with her grandparents and filled in for her grandfather at dedication ceremonies for projects financed by the RFC, including launching warships and inaugurating the Illinois Central’s Green Diamond—the nation’s first diesel-electric streamline train. Her proud grandfather sent her a letter of congratulations after the ceremony that put the train in service and reminded her to write thank-you notes to anyone who extended courtesies to her, a practice Audrey continued throughout her life to the delight of her friends, family, and colleagues when they received one of her gracious handwritten notes (fig. 2).

Fig. 3. Audrey Louise Jones and John Albert Boehck during their engagement. When once asked if they were the most beautiful couple in town, Audrey without missing a beat replied, “No dear, we were the most fun.” Courtesy of Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University.

Audrey transferred to the University of Texas at Austin in 1940 and one year later met Ensign John Boehck at Corpus Christi’s Naval Air Station during the opening of the Officer’s Club. Eight months later, they had one of the first military weddings at Christ Church Cathedral in Houston. As a war bride, Audrey followed her husband—a senior ferry pilot in the Naval Air Ferry Command—from assignment to assignment as the dashing young engineer from Milwaukee, Wisconsin, flew airplanes from factories in California to their new home bases. Audrey entertained troops at the Hollywood Canteen and monitored the sky for suspicious airplanes as a member of the Aircraft Recognition Center for the Department of Defense. Once he was released from service, the couple made their home in Houston, where John developed Boehck Engineering to sell and lease heavy construction equipment while Audrey pursued her love of visual and performing arts (fig. 3). The couple eventually shortened their last name from Boehck to Beck to make it easier for everyone to spell.

Audrey’s grandmother Mary Gibbs Jones served on the MFAH board in the late 1920s and was a founding trustee of the Houston Symphony Society in 1913. The orchestra first performed in one of Jesse Jones’s downtown theaters. Audrey followed her grandparents’ example. In the 1950s, she served as a founding trustee of the Houston Ballet and the Houston Grand Opera and was a trustee of the Houston Symphony Society. The Becks became a visible and enormously popular couple, and their large, cozy, English country-style home on Inwood Drive in River Oaks was one of Houston’s hubs for important gatherings and glamorous events. In contrast to the adjacent manicured lawns, the Becks’ densely forested yard obscured their home from the street and reflected their appreciation of the natural world.

Prominent auction houses and art galleries clamored to display their exquisite paintings in the Becks’ active home during their annual exhibitions in Houston to promote upcoming sales. Audrey took pictures of the paintings with her Brownie camera and wrote notes about them on the back of her photographs. Each year, the Becks noticed some of the paintings returned to their home at higher prices, and at auction other paintings had increased in value and exceeded their advertised prices when sold. Audrey kidded John she could do better buying and selling paintings than he could do in the stock market. Audrey also fell in love once again with the enchanting art that had captivated her as a teenager.

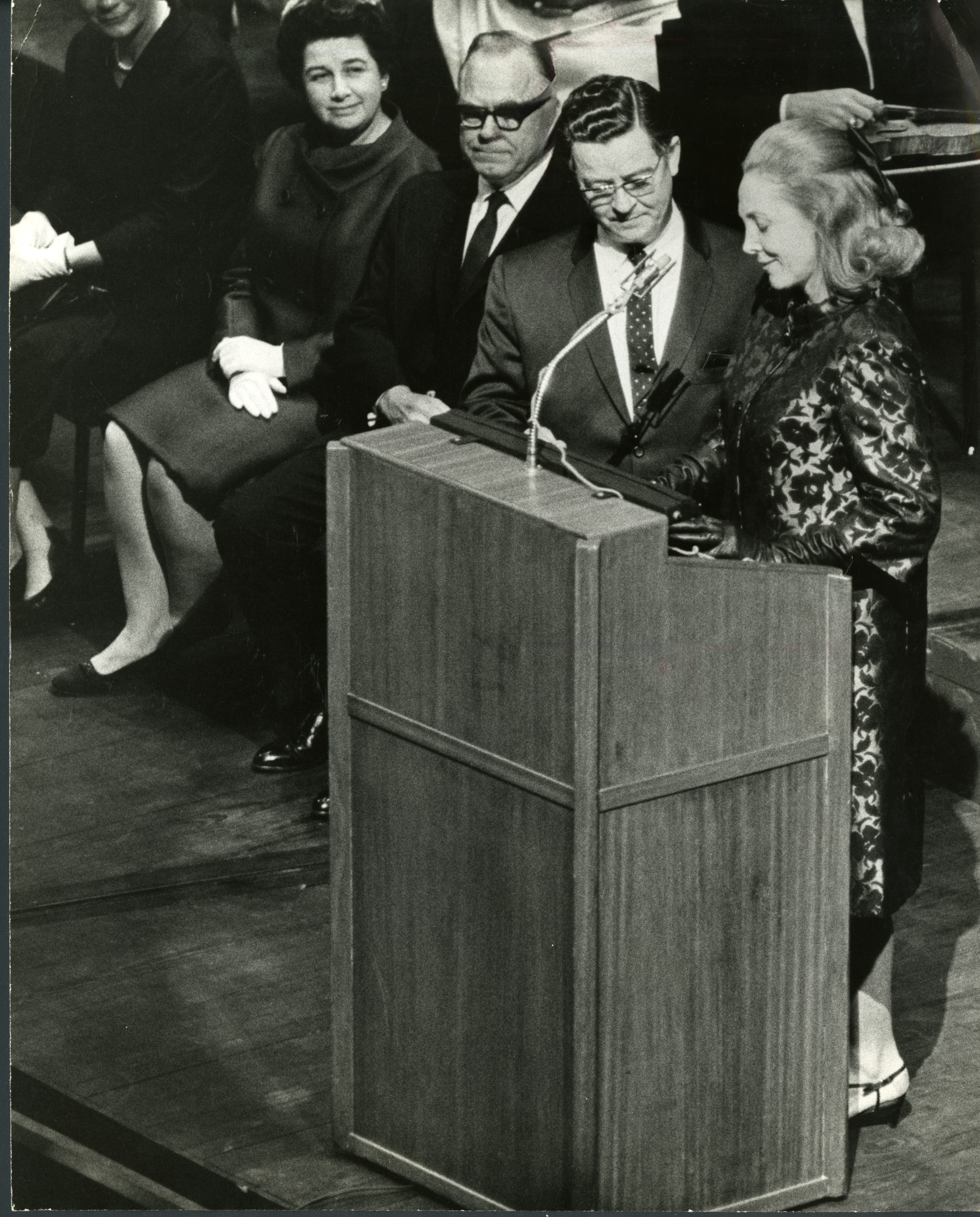

Fig. 4. Audrey Jones Beck handing to Houston Mayor Louie Welch during opening ceremonies the key to the Jesse H. Jones Hall for the Performing Arts. Courtesy of Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University.

At that time, Houston was evolving from a postwar boomtown into a sophisticated urban center. In 1958 the MFAH opened Cullinan Hall, designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. The Johnson Space Center—then known as the Manned Spacecraft Center—formed in 1961 to explore space and to send astronauts to the moon. The forty-four-floor Humble Building, the tallest building west of the Mississippi, opened in 1963, followed in 1965 by the Astrodome, the world’s first multipurpose, air-conditioned domed stadium.

In 1966 the Jesse H. Jones Hall for the Performing Arts opened, spurring the development of downtown’s Theater District and giving the Houston Ballet, the Houston Symphony, the Houston Grand Opera, and the Society for the Performing Arts (now Performing Arts Houston) a modern home where they flourished and earned international acclaim. The city’s first state-of-the-art performing arts center was a gift to the city from Houston Endowment—the philanthropic foundation established in 1937 by Jesse and Mary Gibbs Jones to improve life for the people of Houston.4 Audrey was a dedicated Houston Endowment board member who understood the significance of the gift and was front and center at the transformative building’s development and grand opening (fig. 4).

Fig. 5. Audrey and John Beck at home in front of Maurice de Vlaminck’s Landscape at Valmondois before the October 6, 1966, grand opening of the Jesse H. Jones Hall for the Performing Arts. Courtesy of Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University.

In tandem with the burgeoning development of that decade, the Becks began to assemble the John A. and Audrey Jones Beck Collection. In 1963 John and Audrey purchased the first four paintings that would become part of their collection: Camille Pissarro’s The Goose Girl at Montfoucault (White Frost); Maurice Utrillo’s The House of Mimi Pinson in Montmartre; Marc Chagall’s Woman with Lilacs and Roses; and Maurice de Vlaminck’s Landscape at Valmondois (fig. 5). Other Houstonians were buying beautiful art and assembling collections, but none had the Becks’ priority of creating what they called a “student” or “teaching” collection to provide a comprehensive overview of the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist movements. At a fast clip, within a matter of years the Becks bought dozens of paintings, including those by Pierre Bonnard, Gustave Caillebotte, Henri Matisse, Paul Signac, Vincent van Gogh, and other remarkable painters.

Unknown to most people, Audrey enjoyed painting a copy of each new picture she acquired to understand what an artist was thinking and doing. John decorated his office with Audrey’s replicas, but visitors often mistook them for the originals, so the Becks decided to keep the copies private to avoid any questions about their collection’s credibility. John sold Boehck Engineering in 1965 to manage the finances of their rapidly growing collection after his company had grown from two employees and three pieces of equipment to eighty-five employees with outlets in Texas and Louisiana. John was also a member of the Houston Sports Association, which developed the Astrodome and brought major league baseball to town, and actively served on many boards, including the Houston Chronicle, Texas Commerce Bank (now Chase Bank of Texas), the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and Houston Endowment. Like his Jones in-laws, John helped Houston grow. Between his many responsibilities, he enjoyed hunting, fishing, swimming, playing golf, and buying and selling racehorses.

In addition, Audrey and John traveled the world to assemble their collection. The attractive Texans were recognized for their vivacious personalities, expertise, and determination at auctions in Paris, London, and New York. John’s love of car racing also took the couple to the Monaco Grand Prix, where they were chummy with many of the drivers. Together, the Becks made a great team. Audrey identified what she thought were the best paintings by each artist she wanted in their collection and used that as her standard and starting point for making selections. She wanted an artist’s best work to exemplify each aspect of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. Audrey thought André Derain’s The Turning Road, L’Estaque epitomized Fauvism, and, despite challenges with export licenses, was determined to buy it, even if she had to acquire an apartment in Paris to satisfy residency requirements for the purchase. She did not buy an apartment but instead stayed at the Hotel George V whenever she and John were in Paris, where for several years she visited her painting in storage at the gallery where she had purchased it until the artist’s signature masterpiece was finally shipped to the Becks in Texas.

John was Audrey’s advocate and numbers man. When a painting became available that helped tell the story they wanted to convey, John surveyed the market to see what had sold by that artist and for how much and provided Audrey with a budget. The Becks were admired front-row auction competitors who savored the tense dramatic action. At the auction in Paris where Audrey was set to buy Henri Edmond Cross’s The Flowered Terrace, John reportedly stood up and pleaded for help with translation, since neither of them spoke fluent French. His request was granted, and the Becks placed the winning bid and brought the painting to Houston.

The Becks did not simply check off known artists to include in their collection. They wanted to offer a sweeping view of a specific period that showed the interconnectedness of the artists and the evolution of their works, whether an artist was famous or not. Paintings by Raoul Dufy, Alexei von Jawlensky, and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner—all purchased with foresight by the Becks in the 1960s—surprised and excited Houstonians who were unfamiliar with these great but unrecognized artists. On occasion, the Becks bought two paintings by the same artist to show their distinct change in style, such as Georges Braque’s The Saint-Martin Canal (1906) and Fishing Boats (1909–1910) and Maurice de Vlaminck’s Reclining Nude (1905) and Landscape at Valmondois (c. 1919). They bought two pictures by Gustave Caillebotte, thinking they would sell one as a profitable investment, but they fell in love with it and kept it, too. When asked by new and experienced collectors for guidance about purchasing paintings, Audrey simply and consistently advised, “Buy what you love.” But John did not always love every picture that excited Audrey. Even so, he happily helped her buy what was necessary to complete the story they wanted to tell. As a compromise, they hung Sketch 160A by Vasily Kandinsky behind John’s dining room chair so it was out of his line of vision during meals and dinner parties.

Fig. 6. Amedeo Modigliani’s Portrait of Leopold Zborowski in the Beck’s living room during Christmas. Courtesy of Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University.

The Becks opened their home and their collection to friends, other art aficionados, scholars, and students from all over Texas and the nation. People wandering around their home would see paintings by André Derain, Henri Matisse, Amedeo Modigliani, and Vincent van Gogh in the enormous living room (fig. 6); Kees van Dongen’s The Corn Poppy next to the kitchen door; Pierre Bonnard’s Dressing Table and Mirror in the Becks’ dressing room; and Mary Cassatt’s Susan Comforting the Baby and Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Girl Reading in the sitting room outside of their bedroom. Some lucky guests got a peak at March Chagall’s Woman with Lilacs and Roses over their bed, and a few even saw Edgar Degas’s Russian Dancers in their bathroom. John and Audrey were gracious hosts; they loved giving tours and describing each picture. Audrey explained why and how a painting was created, who influenced the artist, how he or she lived, and if there was a love story associated with the picture. John shared facts about the purchase.

The sophisticated and scholarly Schlumberger heiress Dominique de Menil and her husband, John, who helped expand the international oil services company and was its board chair, were also building a significant collection and promoting modern art in Houston. They supported the MFAH and helped establish the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston and art departments at Rice University and St. Thomas University, where they both curated exhibitions and where Dominique chaired the St. Thomas art department for a while. The Menil Collection and the Rothko Chapel in Houston’s Montrose neighborhood are only two of the de Menils’ lasting efforts to enhance life for people through the power of great art. As the de Menils’ and the Becks’ collections grew in the 1960s and 1970s, the Becks welcomed the de Menils and their students to their home to study, discuss, and enjoy their paintings. Even when they were at their charming Belvedere home by San Francisco Bay with a view of the Golden Gate Bridge, the Becks arranged to open their house in Houston to those who were eager to see their exciting pictures. The Becks had bought their beautiful Belvedere home in 1965, and Audrey sprang to life there because she was free from asthma that kept her indoors most of the time in Houston. She loved to garden, to do errands around town in her bright yellow Volkswagen Beetle, and to host casual lunches, intimate dinner parties, and elaborate Fourth of July celebrations with unobstructed views of fireworks, ships, and sailboats across the bay.

However, the Beck Collection was her priority. In the early 1970s, the Becks continued to add paintings to their collection, including Young Woman Powdering Herself by Georges Seurat. John fussed a little about the price of the Seurat, maybe because it was the most they had paid for a painting. Yet Audrey was determined to buy it since she thought it might be the last outstanding figural painting by the artist on the market for a long time to come. Then tragedy struck.

John Beck died suddenly from a heart attack on September 6, 1973, at home in Houston at the age of fifty-six. The Becks had loaned part of their collection to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, where the museum’s director J. Carter Brown tried unsuccessfully to convince them to donate their paintings to that distinguished institution. Their other paintings were either at the MFAH or on their way there as part of an exhibition planned to celebrate the 1974 opening of the Brown Pavilion. Thomas P. Lee, Jr., who was the associate curator of European art at the time, recalled, “We were all bewildered. We were all just completely in shock about it. It was during that period that I had to consult with Mrs. Beck a number of times about the signage in the galleries and how we were going to name the collection. And this was just one month after Mr. Beck had died. Well, I need not have worried for a single minute. She was just as gracious and wonderful as she could be. John Beck’s passing ended her interest in having the collection at home, but the devastating loss did not stop her from buying paintings.” In his will, John gave his half interest in their paintings to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. The following year, Audrey joined the MFAH board; she became a life trustee in 1984 and served for the rest of her life.

Fig. 7. Then Houston Endowment chairman Jack Blanton and Audrey Jones Beck breaking ground for the Audrey Jones Beck Building at the MFAH. Courtesy of Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University.

In the decade between 1963 and John’s death in 1973, the Becks had bought forty-six paintings. In 1974 and 1975, Audrey bought only one each year. In addition to the blow of her beloved partner’s passing, fine art was becoming an alternative investment class, prices soared, and the pace of additions to the Beck Collection slowed. Even so, through the years without John, Audrey acquired twenty-four masterworks, including those by Paul Cezanne, Paul Gauguin, Edouard Manet, and by lesser-known artists such as Henri-Jacques-Edouard Evenepoel, František Kupka, and Emile Schuffenecker to expand her collection into the all-encompassing teaching tool she had envisioned. The MFAH director Peter Marzio supported Audrey’s intention and affectionately wrote to her on June 12, 1995, after one of her purchases, “The newest addition to the Beck Collection is a real beauty and perfect complement. The Portrait of Émile Bernard will look wonderful amid kindred spirits. I just need to learn to pronounce Schuffenecker!” He signed his note, “Love, Peter.”

After a purchase, Audrey lived with a new painting at home for a few days and on occasion put one in the back seat of her car and drove it to Harris Masterson’s nearby Rienzi (now an MFAH house museum), where the two friends sipped champagne, admired the picture, and talked about art and life before it was installed at the Museum in her collection.

Toward the end of her life, Audrey once again followed in her grandparents’ footsteps. Jesse and Mary Gibbs Jones made substantial donations toward the MFAH’s first building in 1924 and supported the Museum throughout their lives. In the late 1990s, Houston Endowment made a significant donation toward the Audrey Jones Beck Building to house the John A. and Audrey Jones Beck Collection and to provide the Museum with more space for its growing collections and visiting exhibitions (fig. 7). The new building increased the museum’s size from thirtieth to sixth largest in the nation and allowed many outstanding pieces of art that were in storage to be displayed and enjoyed for the first time.

Fig. 8. Audrey Jones Beck with her beloved dog Impy. Indicative of Audrey’s love and support of animals, the Houston Humane Society’s Audrey Jones Beck Adoption Center is named in her honor. Courtesy of Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University.

Audrey continued to build her collection until just months before she died on August 22, 2003. She saw the last painting she purchased only in photographs, but the addition of Piano in the Yellow Music Room II by József Rippl-Rónai brought her collection full circle. Rippl-Rónai is featured in his studio with his wife and dog in Pierre Bonnard’s The Painter’s Studio—one of the first paintings the Becks bought in 1964.

As Audrey intended, the John A. and Audrey Jones Beck Collection shows the evolution of Impressionism and early modern art through the best and most beautiful paintings she could find and afford by both famous and obscure artists. Like her family who came before her, Audrey and her husband, John, created and provided a profound and enduring gift that will enrich life for the people of Houston and art lovers around the world for many generations to come (fig. 8).

—Steven Fenberg

Steven Fenberg is the executive producer and cowriter of the Emmy Award-winning documentary Brother, Can You Spare a Billion? The Story of Jesse H. Jones and is the author of Unprecedented Power: Jesse Jones, Capitalism, and the Common Good.www.stevenfenberg.com

Notes

1. The Jones family’s enduring influence is apparent throughout the Museum District. According to a plaque in the sanctuary entrance of St. Paul’s United Methodist Church, Louisa Jones donated the bells in its tower, “To the glory of God and in memory of Martin Tilford Jones.” Fittingly, the church is across Main Street from the Museum’s Audrey Jones Beck Building. The church’s Youth Building is named in honor of Jesse H. and Mary Gibbs Jones. The Children’s Museum Houston nearby on Binz Street is named in honor of Mary Gibbs Jones. Further, the Jesse H. Jones Graduate School of Business is located on the Rice University campus on Main Street.

2. Audrey Jones wrote in a grade-school essay, “I call him ‘Bods,’ and he is my grandfather. He is very tall, his complexion ruddy, his eyes are steel blue and can either snap or twinkle; his firm mouth and the dimple in his cheek suggest neither the statesman nor the financier. He can and does talk about the things that interest me, and it always surprises me when I remember that he is held in awe by many people.”

3. See Audrey Jones Beck, ed., The Collection of John A. And Audrey Jones Beck, rev. ed. (Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1998), 9.

4. Thomas P. Lee, Jr., interview by Steven Fenberg, Houston History Magazine 4, no. 1 (2004): 17.