Introduction

John A. and Audrey Jones Beck at the opening of the Chillida exhibition in 1966. Courtesy of the Hirsch Archives.

The Purpose

In a letter to Peter Marzio, the director of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, at the time, Audrey Jones Beck very clearly laid out the motivation she and her husband shared in assembling their collection, writing, “The initial purpose of the Beck Collection was to give Houstonians a readily available, representative collection of significant paintings of the colorful, ebullient Impressionist period. John and I did not yield to the temptation to satisfy our personal desires, but held steadfastly to our goal of developing a complete and representative collection to benefit Houston and Houstonians.” Although most private collectors acquire art primarily for their personal enjoyment and only later decide to donate it to the institutions of their choice, the Becks were exceptional in putting the benefit of their fellow Houstonians before their own gratification. This amazing philanthropy seems to have been inbred in Mrs. Beck, the granddaughter of Jesse Jones, businessman, politician, and arguably Houston’s greatest philanthropist. His dedication to his city still reverberates in the countless institutions he established or funded substantially, including the Houston Endowment - a major charitable organization that touches the lives of thousands of Houstonians - that he founded alongside his wife Mary Gibbs Jones.

The Becks concentrated on French paintings but included movements other than Impressionism, spanning from pre-Impressionism to the School of Paris. The Becks acquired their art works at auctions in Paris, London, and New York and through top dealers. In her copious correspondence with various dealers, who offered her many fine objects over the years, Audrey Jones Beck pointed out over and over that it was her mission to assemble a teaching collection in which each artist was to be represented by only one work, unless there was a decisive change in his or her style.

The Beginning

The Becks’ collecting activity began in 1963, but the actual catalyst for it is unknown. Married in 1942, Audrey and John Beck were not newlyweds trying to establish themselves in a new city, but rather they had long been members of Houston society. Respected, wealthy, and engaged in multiple charitable organizations, the Becks had no need to define themselves through an art collection. Their elegant River Oaks mansion already contained a number of paintings and sculptures, but the extent of that collection is only partially known. However, three documents in the Beck Archives give some indication of their tastes. Two of these documents are invoices, dated 1963 and 1964, from Jack Key Flanagan, the paintings conservator of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, listing works he was to conserve. With the exception of Marc Chagall’s Woman with Lilacs and Roses (cat. 14) and Camille Pissarro’s Goose Girl at Montfoucault (cat. 52), none of the works by identified as by Jean-Yves Commère, Raoul Dufy, Michel de Gallard, André Minaux, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Claude Vénard, and Maurice de Vlaminck were eventually donated to the museum. A more comprehensive list, whose author is unknown but who must have had access to the Becks’ home, enumerates additional works including when and where the Becks acquired them and specifies where in the house they were displayed. According to this list, their earliest purchase dated to 1952, when they bought Farmyard by Blair Streeter in New York. Nothing was added for the next five years, but starting in 1957, a year after Audrey Jones Beck’s grandfather Jesse Jones passed away, the couple became very active collectors, buying one, two, and three works a year, all by French painters and mostly bought at galleries in Paris. Despite the fact that the latest acquisition on this list dates from 1966, there is curiously no mention of the paintings by Marc Chagall or Camille Pissarro or of two additional paintings also acquired in 1963—Maurice Utrillo’s The House of Mimi Pinson in Montmartre (cat. 72) and Maurice de Vlaminck’s Landscape of Valmondois (cat. 77). Yet these four works constitute the earliest of the Becks’ seventy-two acquisitions that became the John A. and Audrey Jones Beck Collection. They set both the historical scope as well as the high standard of quality that distinguishes the collection. These artists are major representatives of Impressionism, Fauvism, and the School of Paris and far more illustrious than most of the artists whose works had previously decorated the Becks’ home.

Collecting as a Couple, 1963 to 1973

In many ways the Becks can be considered the ideal collecting couple. The means to purchase these works stemmed from Audrey Jones Beck’s inheritance from her great-grandfather, which allowed her to fulfill her desire to acquire the art she cared for so deeply. As she explained, her love for Impressionism started when she saw works from this movement for the first time during a trip to Paris in the summer of 1938. John, a World War II pilot and businessman, provided the financial acumen. As a businessman he appreciated the profits made by the sale of some of their artworks and thus enthusiastically supported his wife’s endeavors. However, collecting must have meant more to John Beck than just a profitable enterprise. His longtime service on the board of trustees of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, from 1964 to 1973, speaks of his own deep interest in art. In the ten years of collecting together, John and Audrey Jones Beck acquired over half of the works to be donated to the Museum, forty-six of the total seventy-two works, to be precise.

Beginning in 1963, the couple apparently threw themselves into collecting with great zest, acquiring multiple works per year at the major auction houses and from distinguished galleries in Europe and the United States. The following year the Becks set the bar very high by acquiring The Rocks by Vincent van Gogh (cat. 29), a masterpiece from the artist’s most desirable period in Arles and one of the foremost treasures of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Unfortunately, the same year they also made their only mistake when they successfully bid for the pastel Woman at Her Toilet (cat. 68) as a work by Pablo Picasso at a Sotheby’s auction. Actually a work by Joaquim Sunyer Miró, it displayed a forged signature by Picasso. The work had come to Sotheby’s in this state and it was not until 1979 that the signature by Sunyer, which had been overpainted, was discovered. In forty years of collecting, it was the only time they were deceived, a record that speaks for their connoisseurship, their diligence, and their astuteness.

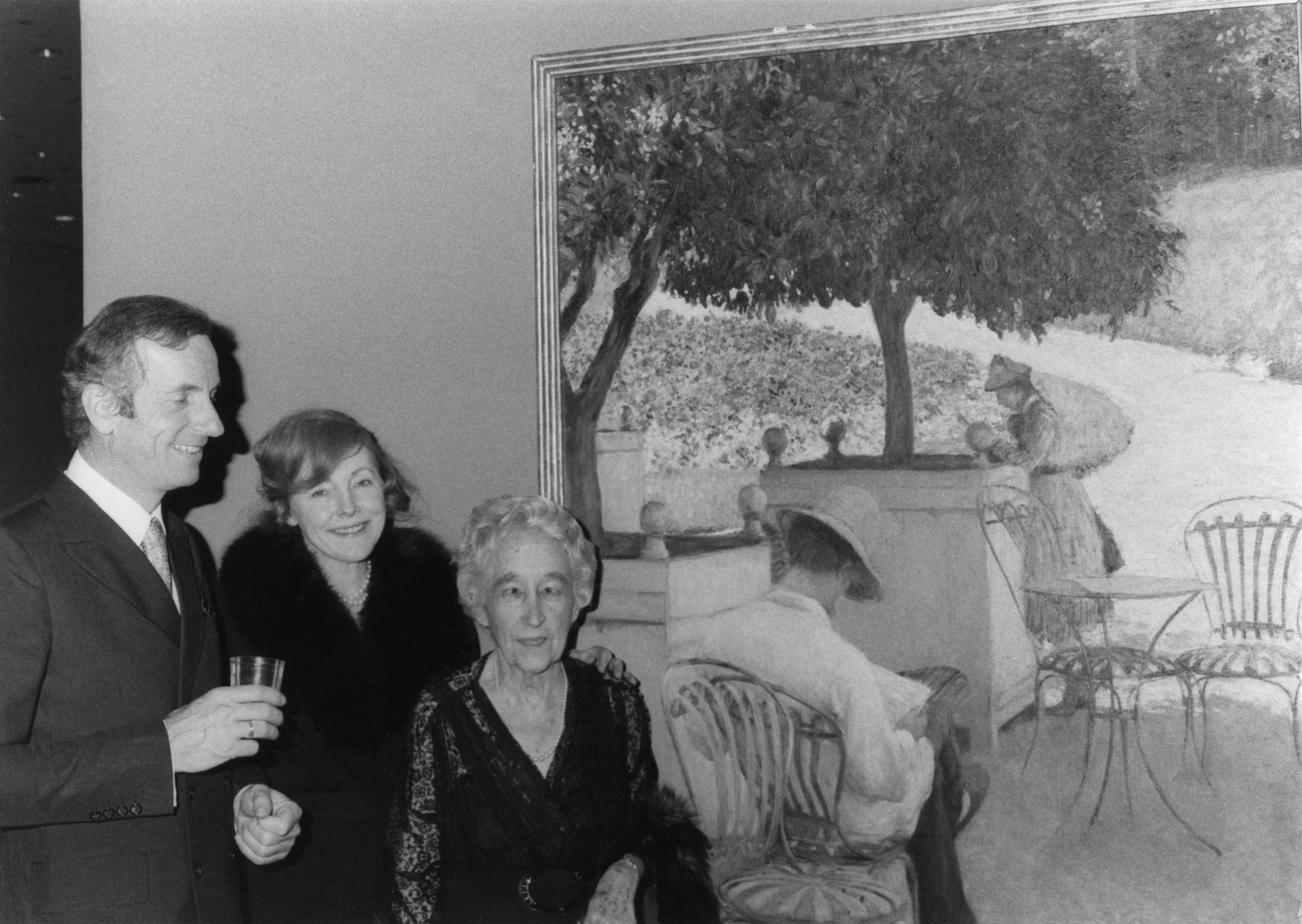

Mrs. and Mrs. Beck with Madame Albert Chardeau, 86, Gustave Caillebotte's niece, in front of Gustave Caillebotte's The Orange Trees, 1976. Courtesy of the Hirsch Archives.

Although Audrey Jones Beck had stated that it was their goal to assemble paintings of the “colorful, ebullient Impressionist period,” only nine of these forty-six paintings acquired by the couple between 1963 and 1973—rounded off by two pre-Impressionist works by Eugène Boudin (cat. 7) and Johan Barthold Jongkind (cat. 32)—are Impressionist paintings. It is, however, a very strong group that includes works by Gustave Caillebotte, Mary Cassatt, Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, and Camille Pissarro. Interestingly and endearingly, the Becks broke their own rule of buying only one work from each painter in the case of Caillebotte, whose Madame Boissière Knitting (cat. 10) and The Orange Trees (cat. 11) they acquired in the same year. They are both Impressionist works, but apparently the Becks decided to retain both, because they had fallen in love with them. The Impressionist paintings are balanced by an equal number of even more ebullient and colorful Post-Impressionist and Fauve works. The Fauves (Wild Beasts) were particularly loved by the Becks. John Beck eloquently expressed his appreciation of this movement when he wrote in 1972, “It is thanks to the genius of Matisse, Derain, Vlaminck, Braque, and Dufy (probably the outstanding Fauves) that today we have a brighter and more colorful world in which to live. . . . Certainly, the ‘Wild Beasts’ have given me, both as collector and as viewer, many happy moments.” By that time, the collection contained works by all these artists, including masterpieces by Henri Matisse and André Derain, the leaders of the group. Although Matisse painted Woman in a Purple Coat (cat. 45) in 1937, many years after the brief heyday of the Fauves, it documents the persistent influence of this movement on Matisse’s entire artistic career. Acquiring André Derain’s astonishing The Turning Road, L’Estaque (cat. 20) was the Becks’ greatest coup. This blazing landscape, the focal point of the collection, was also the most difficult work to acquire. Purchased from Arthur Tooth & Sons in Paris in 1966, it was denied an export license by the French government because of its importance to France’s patrimony. For two years the Becks visited the painting stored in Paris, until after a change in the French government the export license was finally granted, and the painting was allowed to travel to Houston. Among the Fauve paintings is Canal Saint-Martin (cat. 8), a rare Fauve work by Georges Braque, who is best known for having worked closely with Pablo Picasso in the development of Cubism. The Becks were able to fulfill their desire to illustrate a painter’s versatility by buying Braque’s Cubist Fishing Boats (Le Perrey) (cat. 9) at the same time as the earlier Fauve composition.

Although Impressionism and Fauvism are the movements they most intensely collected, the Becks also focused on the colorful but more serene paintings by the Pointillists or Divisionists. They had bought Paul Signac’s masterful Bonaventure Pine in Saint-Tropez, opus 239 (cat. 64) by 1964 and were gratified to be able to add the small but exquisite Young Woman Powdering Herself by Georges Seurat (cat. 63) in 1973. Deeming this study for the larger version at the Courtauld Gallery, London, to be the last chance to acquire a figural painting by the originator of this innovative technique, they were willing to pay a considerable amount for it. Sadly, it was the last work they acquired together.

Carrying on Alone, 1973 to 2003

John Beck passed away unexpectedly from a heart attack in September 1973. Despite the loss of her husband and “numbers man,” Audrey Jones Beck carried on determinedly with the Beck Collection, which she described as “my prime goal in life.” Although the speed of acquisition slowed down considerably, Mrs. Beck continued to add one or two major works virtually every year for the rest of her life. True to her love for the Impressionists, she made some daring acquisitions in this area, including the unfinished proto-Impressionist Little Gardener (cat. 3) by Frédéric Bazille, the superb Toilers of the Sea (cat. 42) by Edouard Manet from the period he was most involved with the Impressionists, and Paul Cezanne’s Bottom of the Ravine (cat. 13), the most expensive work at the time of its purchase. She built out the areas of the School of Pont-Aven, the Nabis, and Symbolism significantly with paintings by their most important representatives, including Émile Bernard, Pierre Bonnard, Maurice Denis, Paul Gauguin, Paul Sérusier, Paul Elie Ranson, and Odilon Redon. She also collected works from the School of Paris, the French avant-garde at the turn of the twentieth century. The Becks’ first acquisition, the Woman with Lilacs and Roses by Marc Chagall (cat. 14), had been followed by Amedeo Modigliani’s important portrait of his friend, patron, and dealer Léopold Zborowski (cat. 46) in 1970, works that she then enhanced by the addition of paintings by Georges Rouault, Henri Rousseau, and Chaim Soutine.

While the Becks’ focus had always been primarily on French painting, they had included works by artists from other nations from the start. These were painters who had either been active in France—such as Chagall, Van Gogh, František Kupka, and Modigliani—or those who were significantly influenced by or had close contact with French artists such as Alexei von Jawlensky, Vasily Kandinsky, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and Théophile van Rysselberghe. Among these, Mrs. Beck’s purchase of Kupka’s Fauve The Yellow Scale (cat. 35), an astonishing self-portrait in vivid shades of yellow, was a brilliant yet daring acquisition. Kupka, Czech but active in Paris, was virtually unknown in America at the time and even in Europe his abstract paintings were far better known than his earlier and rarer Fauve works. Gratifyingly, the work has become one of the Houstonians’ favorites.

The Ones that Got Away

The Becks were discerning collectors, often willing to wait a long time for just the right painting to come on the market, but, of course, there were also a number of hopeful acquisitions that did not materialize. Probably the painting that would have made the most impact was Claude Monet’s stunning Impressionist masterpiece, Woman with a Parasol—Madame Monet and Her Son, 1875. Unfortunately, Mrs. Beck was the under bidder at the auction at the Palais Galliera in Paris in 1965, where it was acquired for Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon’s collection. It is today one of the treasures of the National Gallery in Washington, DC. For a brief moment, the Becks owned Frédéric Bazille’s The Improvised Sick Bay, 1865, which depicts Claude Monet in bed with a wounded leg that he sustained while painting in the Forest of Fontainebleau that summer. The sale of this important pictorial document of the future Impressionists working together was preempted by the French government and the painting went to the Louvre, then the Jeu de Paume, and is today in the Musée d’Orsay.

Impressionist and Post-Impressionists Paintings in Lower Jones Galleries of the Caroline Wiess Law Building, 1975. Courtesy of the Hirsch Archives.

Over the years, the Becks also sold a number of works, often adding a different painting by the same artist and thereby refining their collection. A list in the Beck Archives, which probably dates from the late 1970s and that has annotations in Mrs. Beck’s hand, indicates that paintings by Françoise Adnet, Pierre Bonnard, Jean Commère, Charles François Daubigny, Raoul Dufy, Michel de Gallard, Armand Guillaumin, Bernard Lorjou, Albert Marquet, Jules Pascin, André Dunoyer de Segonzac, Louis Valtat, and Marcel Vertès had been sold over the years. Of the two posters by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec on this list, one was sold, but next to the poster of La Goulue, Mrs. Beck wrote “give in will to MFA,” an indication of her eventual donation. Three paintings that had already made their way to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, as long-term loans were sold before Mrs. Beck’s will came into effect. Georges Rouault’s Circus Girl, 1905, and The Clown, c. 1908, included in the 1974 edition of the Beck Collection catalogue, were cut from the collection. The former was sold, the latter given to Harvard University’s Fogg Museum. They were replaced by Rouault’s Three Judges (cat. 58), a much more impactful composition. Similarly, Young Blonde Girl with a Chignon, c. 1888, by Van Rysselberghe, which was included in 1986 edition of the catalogue, was exchanged for his Portrait of Jeanne Pissarro (cat. 60), acquired by Mrs. Beck in 1989.

The Beck Collection at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Audrey Jones Beck with Jack Blanton at the groundbreaking of the Audrey Jones Beck Building. Courtesy of the Hirsch Archives.

The Becks had opened their home to students of the different Houston universities, so that they could study the collection, but that was by necessity only a fraction of the Houston public the Becks wished to reach. The logical venue was the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, with which they had a long and close connection. Audrey Jones Beck’s grandmother, Mary Gibbs Jones, had been a member of the board of trustees already in the 1920s. John Beck joined the board in 1964 and in 1972 the Becks established a substantial fund for the Museum to purchase Impressionist, Post-Impressionist, and early Modern paintings. They also donated the first painting from their collection, Armand Guillaumin’s The Seine in Paris (cat. 30) in 1971. Following her husband’s death, Mrs. Beck was elected to the board in 1974 and established herself as a major donor by giving the paintings by Pierre Bonnard, Georges Braque, Mary Cassatt, Honoré Daumier, André Derain, Vincent van Gogh, Vasily Kandinsky, Henri Matisse, and Paul Signac to the museum. Together with the previously donated work by Guillaumin, the donation of these masterpieces was momentous for the collection of the European art department, significantly increasing its holdings of nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century art. At that time, Mrs. Beck drew up a “Memorandum of Understanding” that listed which works were to be added to the collection with the help of the museum’s curator of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings and the director and specified that the collection was intended primarily as an educational exhibition for students, to be displayed in contiguous galleries. Three years later, she further specified that the paintings could not be double hung as they were in European museums, saying “I’d rather damn well spend my money on myself.” In 1983, she stipulated that no more than two paintings could be out of the collection at the same time and that the Derain was never to leave the country. She even denied it to Jacques Chirac, the mayor of Paris, when his office asked to borrow the painting. By 1987, the collection had grown to fifty-eight works and was awarded its own suite of five galleries. A letter from Isaac Arnold, Jr., Chairman of the Board of Trustees, documents that five gallery spaces on the upper floor of the Caroline Wiess Law Building were to be designated as “The Audrey Jones Beck Galleries.” Arnold further points out that her collection, which he calls a cornerstone of the museum, will be transferred to the new building, which, however, was still very much in the planning phase. According to her wishes expressed in the Education Policy of the Audrey Jones Beck Endowment Fund, dated 1991, the Beck Collection paintings must be displayed on peach-colored walls in contiguous galleries. Furthermore, they may not be loaned, deleted, sold, or deaccessioned at any time. The museum has scrupulously adhered to her wishes. Over the years, the Becks worked with four directors of the Museum: James Johnson Sweeney, Philippe de Montebello, William C. Agee, and Peter Marzio. Although all of them were very keenly aware and supportive of the Becks’ collecting endeavors and worked diligently toward attracting the collection to the museum, it was Peter Marzio who shepherded the arrival of the majority of the collection in 1998. Marzio was also the driving force behind the construction of the museum’s Audrey Jones Beck Building, a masterpiece by Rafael Moneo that opened in the spring of 2000. Generously supported by the trustees, the building had been made possible in large measure through a substantial donation by the Houston Endowment, created by Mrs. Beck’s grandfather Jesse Jones. “The Audrey Jones Beck Galleries,” located on the upper of floor of the building, were installed according to Mrs. Beck’s wishes and continue to be the elegant repository of her magnanimous donation.

As soon as the Beck Collection paintings entered the museum—whether as gifts or loans—they were under the immediate aegis of the museum’s curators of European art. During Mrs. Beck’s lifetime her collection was thoughtfully administrated and enhanced by Tommy P. Lee, Jr., George Shackelford, Edgar Peters Bowron, and Mary Morton who helped Mrs. Beck locate great works on the international art market and bring them into the collection, while Helga Aurisch, David Bomford, and Gary Tinterow, director and head of the European department, continued to add to the collection after Mrs. Beck’s passing with the resources she made available through the Audrey Jones Beck Endowment Fund. Since 2003, six fine paintings have been added: Mary Cassatt’s Young Woman (cat. 50), Paul Gauguin’s Still Life with Mangoes and a Hibiscus Flower (cat. 26), Achille Laugé’s The Road (cat. 37), Max Liebermann’s Terrace in the Garden near the Wannsee toward Northwest (cat. 40), Daniel de Monfreid’s Self-Portrait (cat. 49), and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s Mademoiselle Platzer in the Garden of Mr. Forest (cat. 69). Thanks to the endowment, the collection has remained a dynamic and growing part of the museum.

Although Mrs. Beck was not an art historian, she was very interested in documenting her collection in a catalogue. With the input of the curatorial staff, she helped to compile three versions of the catalogue, published in 1974, 1986, and 1998, emphasizing repeatedly that it was her wish that the catalogue should include “correct information, but interestingly written to charm a novice.” Presciently, she allocated funds for future editions of the catalogue. Because more than twenty-five years have passed since the last version in which the most recent acquisitions had not been included, a new catalogue is called for. The much expanded present catalogue, which brings the scholarship up to date and situates each work within the artist’s oeuvre and the artist within his or her period, also includes new provenance findings, extended bibliographies, as well as comparative images. We hope it meets Mrs. Beck’s stipulations of providing scholarly information written in an engaging manner. Since the paintings themselves cannot travel, this digital online format is designed to make this outstanding collection available not only to Houstonians, but to an audience far wider than John and Audrey Jones Beck could have imagined.

Helga Kessler Aurisch

Curator Emerita, European Art

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston