“Though the colors [of autumn flowers] are bright, they fade away. Who in this world of ours may continue forever? Crossing today the boundaries of the physical world—no more dreams or intoxication.”1

While not strictly a Zen subject per se, the Iroha, a pangrammatic poem containing the entire Japanese syllabary, is supposed to have been composed by the Shingon sect Buddhist monk Kūkai during the ninth century and expresses sentiments of life’s ephemeral transience and the desire to transcend illusion, both important Zen concepts.

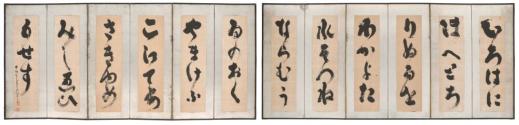

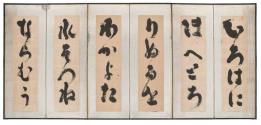

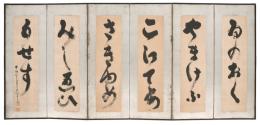

In comparison to the elegant and sinuous kana on Tesshū’s iroha screens, Nantenbō’s calligraphy is composed of thick and even brushstrokes, rendered in dark ink with jagged, splashy edges, elements typical of the monk-painter’s dynamic yet earnest style.

—Bradley Bailey