Echoes of the Sound of One Hand

By Bradley Bailey, The Ting Tsung and Wei Fong Chao Curator of Asian Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Daisetz Suzuki and the Zen of Painting

“People are talking about . . . the Columbia University classes of the great Zen Buddhist teacher, Dr. Daisetz Suzuki, who sits in the centre [sic] of a mound of books, waving his spectacles with ceremonial elegance while mingling the philosophical abstract with the familiar concrete: ‘To discover one is a great achievement, to discover zero, a great leap’; or another time: ‘Have no ulterior purpose in work, then you are free.’”1

Fig. 1. Tom Funk, Header illustration [of D. T. Suzuki for “Profiles: Great Simplicity,” (August 31, 1957)], The New Yorker. © Condé Nast, August

This statement, in the January 15, 1957, issue of Vogue, was one of the earliest signs of Dr. Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki’s influence in the transmission and reception of Zen in American popular culture. It was, however, far from the last. The next month, Time published a two-page article on Zen and Suzuki, noting that a “Buddhist boomlet is underway in the US,”2 and in August of that year, the New Yorker published a twenty-page profile by Winthrop Sargeant on the professor, complete with a cartoon portrait (fig. 1). Titled “Great Simplicity,” the article refers to Zen as “a subject of considerable mystery to the relatively few people in the country who have heard of it at all” and also mentions that Zen had become something of an “intellectual fad,” especially popular with psychoanalysts and artists.3

Although Zen’s ascent in New York may have seemed sudden, and expressly foreign, as the writers’ frequent mentions of Suzuki’s Japanese appearance and manner suggest, Suzuki had been working for decades to disseminate his thoughts and writings on the subject. A favored student of the Zen master Shaku Soen (who also continued the painting tradition of Zen monks (see cat. 103), Suzuki was first sent to the United States in 1897 as a translator for a small publishing house in Illinois. He supplemented his prolific translations and publications with lecture tours, beginning as early as 1906. Not until 1949 was he hired as a lecturer at Columbia University.4

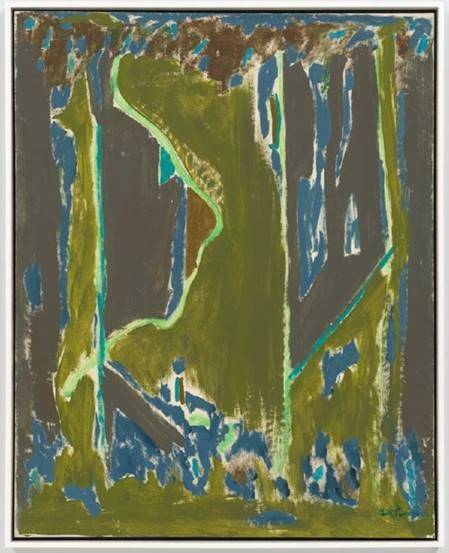

Fig. 2. Philip Guston, Passage , 1957–58, oil on canvas, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, bequest of Caroline Wiess Law, 2004.20. © Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy Hauser & Wirth

As noted by the magazine writers, many of Suzuki’s early students were artists, including John Cage, Ad Reinhardt, Philip Guston (fig. 2), Mark Tobey, and gallerist-painter Betty Parsons (fig. 3).5 Though records indicate their attendance, it is of course impossible to know precisely how much of Dr. Suzuki’s lectures they could understand—or indeed even hear. As John Cage would later describe, many “students” were not even taking the course for credit, and the room’s acoustics and location often rendered the already impenetrable concepts of Suzuki’s Zen fully inaudible:

During recent years Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki has done a great deal of lecturing at Columbia University. First he was in the Department of Religion, then somewhere else. Finally he settled down on the seventh floor of Philosophy Hall. The room had windows on two sides, a large table in the middle with ash trays. There were chairs around the table and next to the walls. These were always filled with people listening, and there were generally a few people standing near the door. The two or three people who took the class for credit sat in chairs around the table. The time was four to seven. During this period most people now and then took a little nap. Suzuki never spoke loudly. When the weather was good, the windows were open, and the airplanes leaving La Guardia flew directly overhead from time to time, drowning out whatever he had to say. He never repeated what had been said during the passage of the airplane. Three lectures I remember in particular. While he was giving them I couldn’t for the life of me figure out what he was saying. It was a week or so later, while I was walking in the woods looking for mushrooms, that it all dawned on me.6

Fig. 3. Betty Parsons, Maine 2, 1957, acrylic on linen, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, museum purchase funded by contemporary@mfah, 2022, 2022.106. © 1957 Betty Parsons and William P. Rayner Foundation

Cage’s delayed, seemingly unprompted flash of insight is characteristic of Zen Buddhist encounters between master and student throughout the history of the religion, seemingly irrational and dialogic in nature and most fully embodied by the Zen koan, which Suzuki often invoked in his lectures, repeating Hakuin’s famed query: “What is the sound of one hand clapping?” Indeed, Winthrop Sargeant, in his lengthy New Yorker profile, declared the koan as “sufficiently baffling to unhinge the normal thinking person’s mind.”7 For Suzuki, the koan was indelibly linked to the monk-painter Hakuin Ekaku, whose numerous koan paintings illustrate some of these baffling—yet profound—concepts (see cats. 5, 16). In many of his publications on Zen, Suzuki reprinted well-known works by Hakuin, Sengai Gibon, and other Zen painters from both Japan and China. For instance, in his seminal book Zen and Japanese Culture (1959), Suzuki reproduced a portrait of Zen First’s Patriarch, the Indian monk Bodhidharma, or Daruma in Japanese, by Hakuin, a version of which also features in this catalogue (see cat. 28). In that expansive tome, he used such images simply as illustrations rather than to fully engage with the histories and techniques of the artists and monks who made them. However, in other writings, Suzuki singled out Hakuin’s reformed version of Rinzai Zen, stating explicitly that “Hakuin Zen is koan Zen through and through.”8

As Suzuki explained, Hakuin’s form of Zen was especially suited to novice students, though it was not without its drawbacks, as it could convey a form of Zen that is overly ritualized and performative. He wrote, “It has both the dangers and the benefits inherent in such an artificial system. . . . One may say that koans are also beyond our grasp as well, but when you work on a koan it is right there before you, and all your effort can be concentrated on it. . . . Koan Zen provides steps for the practitioner, and if he can somehow get a foothold on the first step he is brought along from there without much difficulty. This is clearly a problem, though one cannot deny its convenience. This is the real reason why masters of the past devised the method of giving koan to their students. It was, as I have been saying, an expression of the deepest compassion—what Zen calls ‘grandmotherly kindness.’”9

Accounts of Suzuki’s teaching style indicate that he frequently invoked the koan as a didactic tool, which proved useful—if at times “sufficiently baffling”—for his students. One, Philip Guston, once mused, “Sometimes I think of the Zen koan. I know very little about Zen but I think somehow I am undergoing the koan.”10

Fig. 4. Franz Kline, Corinthian II, 1961, oil on canvas, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, bequest of Caroline Wiess Law, 2004.26. © The Franz Kline Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The prevalence of “Hakuin Zen” within Suzuki’s lectures may thus partly explain their appeal—and apparent usefulness—to new students of Zen. With his repeated assertions on healing the mind and reconciling external reality and internal thought, Suzuki also understood well why his approach to Zen teaching would appeal to psychologists and psychoanalysts. According to a reporter for Time, “Painters and psychiatrists seem especially interested in Zen, he finds. Psychoanalysts, says Dr. Suzuki, have a lot to learn from Zen . . . ‘They go round and round on the surface of the mind without stopping. But Zen goes deep.’” The article goes on to say that Westerners have trouble with Zen because they attempt to analyze it dialectically, “either-or, object-subject, positive-negative. Zen sees only one instead of two.”11

The metaphor of going “round and round on the surface of the mind” conjures the image of Hakuin’s Ant on a Stone Mill (see cat. 5). As a painting, this work allows the viewer, student, or potential convert to see in a very literal sense the shift in perspective that reveals the ant’s internal world—one of constant effort, seeming movement, and near-Sisyphean struggle—to be an illusion. Suzuki’s casual analogy hints at the usefulness and importance of both the koan and, crucially, Zen painting to the transmission, study, and spread of Zen—and thus also explains Hakuin’s importance as both monk and painter to Suzuki. However, Suzuki did not fully explain Zen’s specific appeal to artists.

In his essay Zen and the Modern World, Suzuki wrote that Zen’s resonances in so many diverse areas of modern culture, ranging from semantics to philosophy to art, are indicative of contemporary societal problems or “modern maladies”: “We have lost our spiritual balance and feel shaky about our destiny as human beings. We are negating everything that has held us somehow together not only socially or communally but essentially as individuals . . . the modern man refuses to acknowledge this fact and tries all the harder to ‘think and think’ as if thinking that has lost its anchorage could keep us steady with any feeling of security.”12 Though he did not reference artists specifically, he did cite the Beat Generation as an example of young people struggling with this sense of modern alienation and detachment. His words resonate with an explanation once offered by Cage, who was brought to Zen seemingly—and perhaps appropriately—by chance: “I got involved in Oriental thought out of necessity. I was very disconcerted both personally and as an artist. . . . I saw that all the composers were writing in different ways, that almost none of them, nor among the listeners, could understand what I was doing . . . so that anything like communication as a raison d’être for art was not possible. I determined to find other reasons . . . I found the flavor of Zen Buddhism appealed to me more than any other.”13

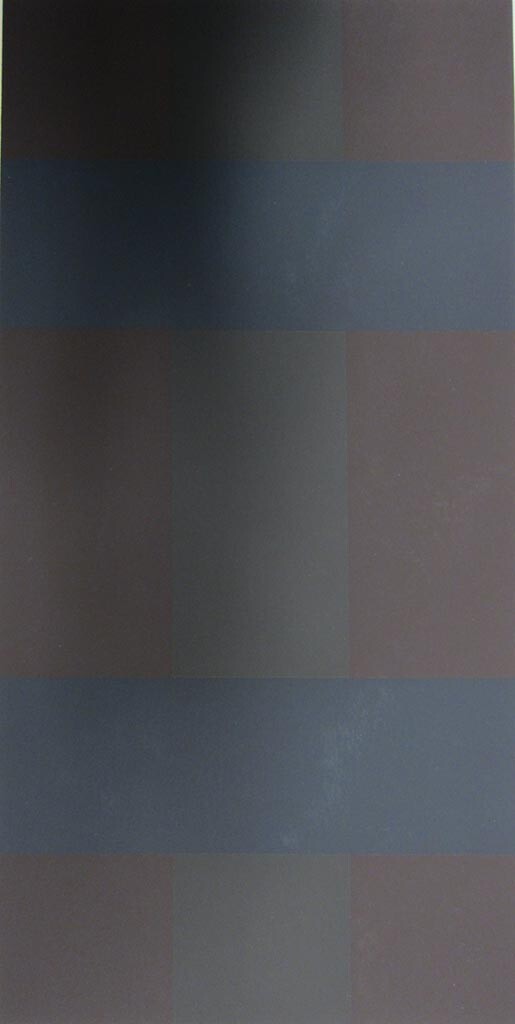

Fig. 5. Ad Reinhardt, Untitled, from 10 Screenprints, 1966, screenprint in maroon, blue, and brown on cream wove paper, edtion 151/250, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, gift of Barbara Rose, 86.370.0. © 2023 Estate of Ad Reinhardt / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In search of direct experience, Cage also explored musical composition, meditation, chess, and psychedelic mushrooms. Through all these pursuits, including Zen, the artist hoped to “wake up to the very life we’re living”—a succinct metaphor for Zen’s flash of enlightenment.14

Articles about Professor Suzuki often mentioned not only his general appeal but also his unique approach, which blended aspects of Zen with ideas from Buddhism, Taoism, Western philosophers, thinkers such as Simone Weil, Søren Kierkegaard, and Carl Jung (who would eventually write the foreword to the 1939 edition of Suzuki’s Introduction to Zen Buddhism), and even the Transcendentalism of Ralph Waldo Emerson, who, Suzuki once wrote, “is talking about Zen, or at least Zen-like practice.”15 In addition to his command of the English language and prolific publications, Suzuki augmented his influence through his apt use of metaphor, analogy, and comparison, which distinguishes him from the more traditionally impenetrable Zen masters. The New Yorker profile even noted his “rather unorthodox interest in finding a logical explanation—as far as that is possible—of Zen behavior in its relation to Western thought and to Buddhism in general, and this interest has led him into a career that, as orthodox Zen circles see it, has several displeasing aspects. . . . Dr. Suzuki’s approach to Zen is, in fact, more like that of a Western philosopher than a true Zen disciple.”16

As Yukio Lippit explores in his essay in this digital publication, Hakuin also took a unique and unusual approach to the dissemination of Zen, incorporating folk gods (cat. 23), comprehensible analogies (cat. 5), everyday objects (cat. 17), popular cultural references (cat. 4), and vernacular language (cats. 19, 22) into his sermons and his paintings. In many ways, Suzuki’s wide-ranging and animated lectures, as well as his constant comparisons and analogies, echo Hakuin’s approach. Despite the fact that Suzuki was not a monk himself, his Zen was Hakuin’s Zen, and he extended the influence of that eighteenth-century monk to twentieth-century America. As explained by Professor Lippit, Hakuin’s reformed approach proved attractive to nontraditional audiences, including farmers and merchants. Similarly, Suzuki’s language was tailored to his audience, something noted in the New Yorker by Sargeant, who wrote that Suzuki’s “intimate knowledge of the English language and of Western habits of thought—things that few orthodox Zen masters had ever concerned themselves with—had enabled him to bridge the chasm between the Orient and the Occident.”17

The New Yorker profile gave Suzuki most of the credit for the dissemination of Zen in America, yet he was far from alone. Although he is rightly regarded as Zen’s most famous proponent and prolific interlocutor, America in the twentieth century saw major growth in the publication of literature on Zen and its relationship to a wide variety of topics. In addition, cultural exchanges, tourism, and even conversions were also important to the spread of Zen.18 Many artists experienced Suzuki’s influence only indirectly, such as Franz Kline (fig. 4), who worked with Cage at Black Mountain College in 1952 and whose work engaged with Zen painting on a more formal than intellectual level. Others who studied with Suzuki, such as Ad Reinhardt (fig. 5), traveled to Japan; for Reinhardt, the direct relationship of Zen and painting remained strongly influential. In words that resonate strongly with his deceptively “empty” black works, Reinhardt wrote while in Japan in 1958, “Zen—how to make manifest meaning of empty space in a picture.”19 He would later state that Zen painting was “one of the greatest achievements in art and human history.”20

Fig. 6. Robert Motherwell, Primordial Sketch #16, 1975, acrylic on canvas panel, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Foundation and the Dedalus Foundation, 2001.618. © Dedalus Foundation, Inc. / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Although Suzuki was not the lone disseminator of Zen in America, he had an outsize influence among artists, and his frequent mention of painting clearly had an impact on his audience. He not only typically used paintings as illustrations for his writings, but also frequently invoked the act of painting—particularly sumi-e ink painting—in his lectures and conversations as a metaphor for Zen itself. The New Yorker quoted Suzuki at length on the subject:

Life is a sumiye [sic] painting which must be executed once and for all time and without hesitation, without intellection, and no corrections are permissible or possible. Life is not like an oil painting, which can be rubbed out and done over time and again until the artist is satisfied. With a sumiye painting any brush stroke painted over a second time results in a smudge; the life has left it. All corrections show when the ink dries. So is life. We can never retract what we have once committed to deeds; nay what has once passed through consciousness can never be rubbed out. Zen therefore ought to be caught while the thing is going on, neither before nor after. It is an act of one instant. . . . This fleeting, unrepeatable, and ungraspable character of life is delineated graphically by Zen masters.21

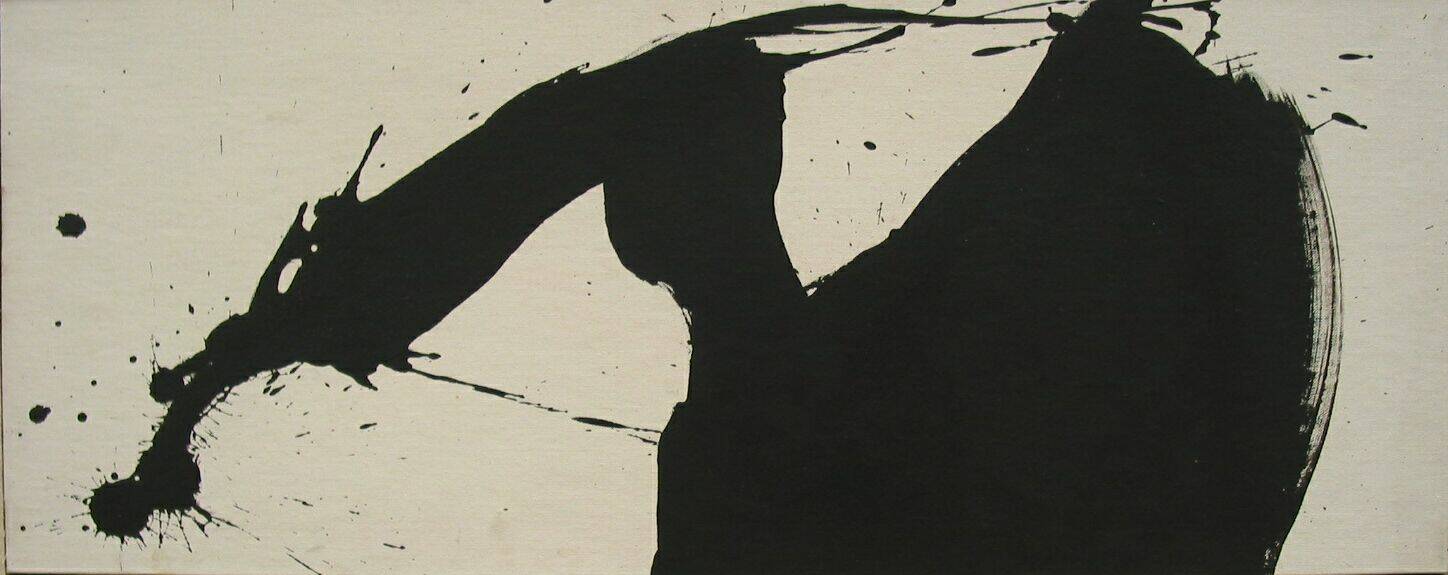

Fig. 7. Mark Tobey, Above the Trees, 1957, sumi ink on kozo paper, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, gift of Mrs. Efrem Kurtz, 2000.335. © Mark Tobey / Seattle Art Museum, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Suzuki’s language expresses the importance of Zen painting to the experience of Zen itself. In addition, his emphasis on the instantaneity, even spontaneity, of a single moment would have resonated strongly with the work of painters like Robert Motherwell (fig. 6), Mark Tobey (fig. 7), and other gestural and Abstract Expressionist painters. Even conceptual artists like Cage, though not a painter, sought to re-create this direct, instantaneous, and fleeting moment in art. These various interpretations of Zen painting would also be influential in Japanese art of the twentieth century, as seen in Inoue Yūichi’s 1234567 (see cat. 105), which explores the notion of seriality, repetition, and order through instantaneous and messy calligraphic gestures, adding an element of random chance to the otherwise logical sequence. Similarly, Suda Kokuta’s tea screen (see cat. 106) seems to reinterpret ideas of conceptual art through Japanese calligraphy, listing various types of paintings around the large central kanji (Japanese character) for “picture.” The apparent gestural quality of each brushstroke forces the viewer to reconcile the duality of the work’s status as a non-picture (in that it does not literally depict anything) and a picture, a design composed of attractive ideograms and characters. The characters, when viewed as if detached from any linguistic significance, can thus render the work “a picture.”

Suzuki’s prominent role in the interpretation and dissemination of Zen, especially among artists, and his repeated invocations of painting as a metaphor for the Zen experience have given Zen painting an equally prominent role in the understanding of Zen. In addition, his frequent use of the koan has also imparted great importance to Hakuin’s version of Zen in the American interpretation of Zen. And in many ways, the Gitter-Yelen Collection of Zen paintings, with its renowned holdings of paintings by Hakuin, is yet another iteration of this tradition. Many works from their collection, including key pieces by Hakuin, are now part of the permanent collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, where they can be shown in dialogue (an important component of Zen teaching) with equally important works of American and international modernism. Though Hakuin’s “sound of one hand clapping” may not resonate loudly in many of these masterpieces of modernism, its echoes can be heard.

Notes

1 “People Are Talking About,” Vogue (January 15, 1957): 98.

2 “Religion: Zen,” Time (February 4, 1957): 65–66.

3 Winthrop Sargeant, “Profiles: Great Simplicity,” New Yorker (August 31, 1957): 34.

4 Helen Westgeest, Zen in the Fifties: Interaction in Art between East and West (Netherlands: Waanders Publishers, 1997), 52.

5 Ibid., 52.

6 John Cage, Silence: Lectures and Writings (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1973): 262.

7 Sargeant, “Profiles,” 35.

8 D. T. Suzuki, Selected Works of D. T. Suzuki, vol. 1 (Oakland: University of California Press, 2015), 90.

9 Ibid.

10 Dore Ashton, “Philip Guston,” Studio International 169, no. 862 (1965): 66.

11 See “Religion: Zen.”

12 D. T. Suzuki, “Zen and the Modern World,” Japan Quarterly (October–December 1958): 452–61.

13 Cage, in an interview with Paul Cummings, May 2, 1974, Archives of American Art. As cited in Westgeest, Zen in the Fifties, 55.

14 Ibid., 57.

15 D. T. Suzuki, Emaason to zengakuron (Emerson’s Theory of Zen), 1896, reproduced in Suzuki Daisetzu Zenshuu 30 (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1965), 43. See also Shoji Yamada, Tokyo Boogie-woogie and D. T. Suzuki, trans. Earl Hartman (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2022), 118.

16 Sargeant, “Profiles,” 36.

17 Ibid., 52.

18 For more criticism in this regard and further reading on this subject, see Gregory Levine, Long Strange Journey: On Modern Zen, Zen Art, and Other Predicaments (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2017): 107–8.

19 Reinhardt Papers, Archives of American Art, as cited in Westgeest, Zen in the Fifties, 74.

20 Ad Reinhardt, “Cycles through the Chinese Landscape,” Art News 53, no. 8 (1954): 24.

21 Sargeant, “Profiles,” 47.