Collector’s Statement

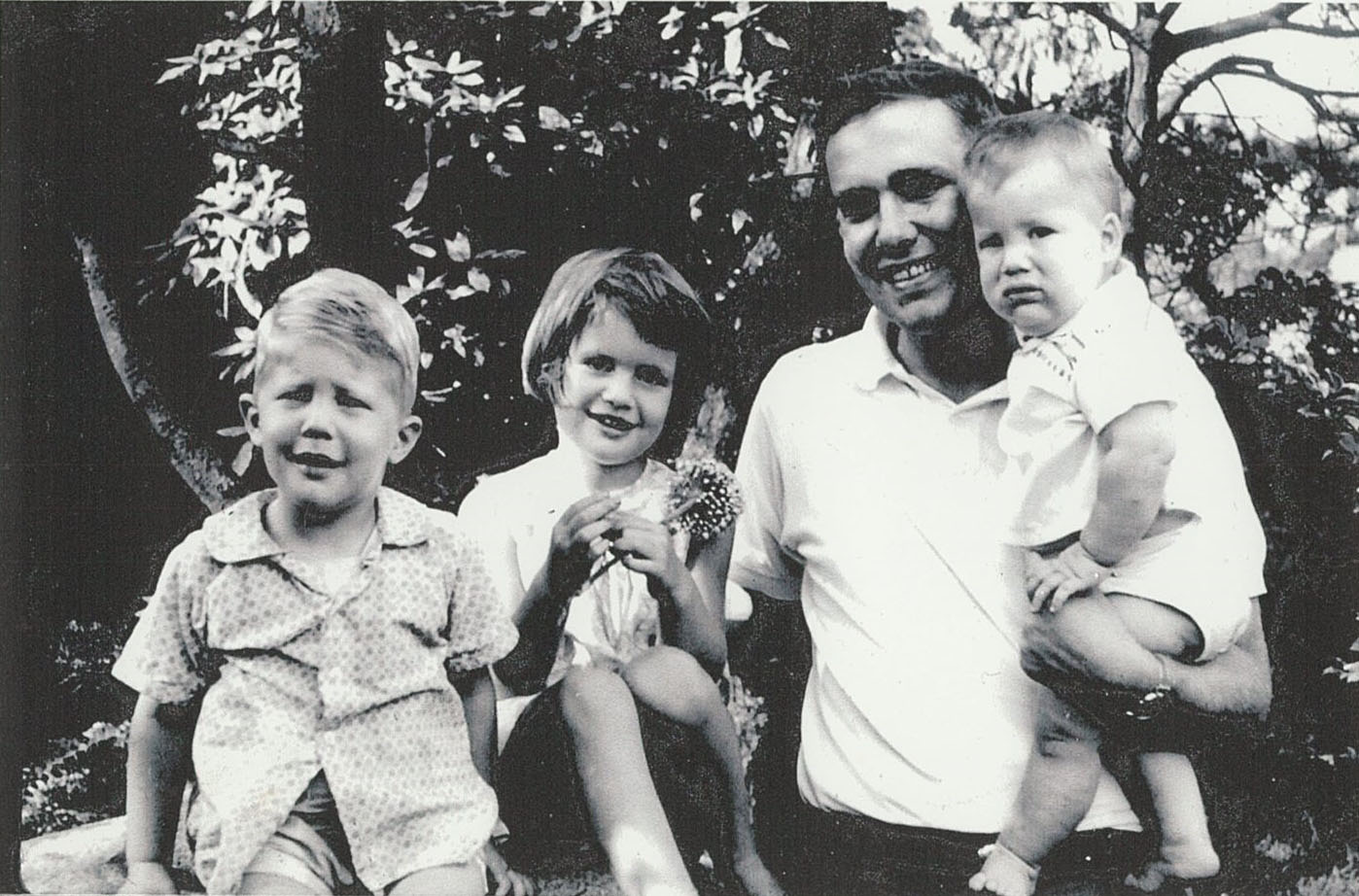

Fig. 1. Kurt (age 26) with his three children (left to right) Greg, Linda, and Ricky, near their home in a Japanese village close to Hakata Airbase, Kyushu, Japan, 1963.

It all began in 1963. After completing my medical internship in New York, I was drafted into the United States Air Force and spent two years in Japan as a flight surgeon. I was twenty-six. I lived in a small fishing village, Saitozaki, in a typical Japanese house with tatami floors near the Hakata Air Base (now Brady), twenty miles from the city of Fukuoka on the island of Kyushu. My late wife, Millie Hyman Gitter, our three young children (fig. 1), and I rapidly became enamored with Japanese culture, food, and the general lifestyle, which was a marked contrast from the urban intensity of our prior life in New York City.

Although undoubtedly my experience in Japan gave direct rise to my passion for the collecting of Japanese art and Zenga, it was my background and upbringing that prepared me for this encounter. My parents were European Jews who fortunately were able to immigrate to the United States in November of 1938, six months after the Nazi invasion of Vienna. Well-educated and cultured, they gave up their successful careers and personal property in order to leave Austria and escape the Nazi onslaught. I was one and half years old when we arrived in New York. Although we lived a more humble lifestyle in America, my parents encouraged my exploration of culture and the intellectual world. In doing so, they fostered my innate interest in art.

Fig. 2. Kurt Gitter and Shigehiko Yanagi (1933–2018), in his Kyoto gallery on Nawate-dori, 2016.

As a premed college student at Johns Hopkins University, I took many art history courses, and during my internship and studies at medical school in New York City I routinely visited museums and galleries. Art, along with medicine, had become my passion. In particular, my attraction to Abstract Expressionism conditioned the appeal that Zenga artworks would hold for me. In 1956 I met Philip Pearlstein, a young American realist painter, who introduced me to many other artists, including those practicing Abstract Expressionism such as Franz Kline and Robert Motherwell. We often visited the Cedar Bar in Greenwich Village, where I met a plethora of emerging artists who would form the historical foundation of Abstract Expressionism. This exposure awakened my instinct for collecting.

After returning from Japan in 1964 and beginning to practice medicine, from the late 1960s we traveled annually to Japan to visit museums and art dealers. The dealers patiently taught me a great deal about various artists and schools of art in the Edo period (1615–1868). Religiously, I took notes and photos of all objects of interest, as little was available in English in those early years. Although I never formally studied Japanese, I was able to communicate well enough to manage viewing art and financial transactions. In this postwar period, Japanese works of art, particularly Zenga, were plentiful and affordable. I began acquiring them. Guided by my eye, I would enter anywhere I found a painting of interest displayed in a window. The visual dynamism and immediacy of Zen painting struck me much like the bold Abstract Expressionist action paintings then flourishing in New York City.

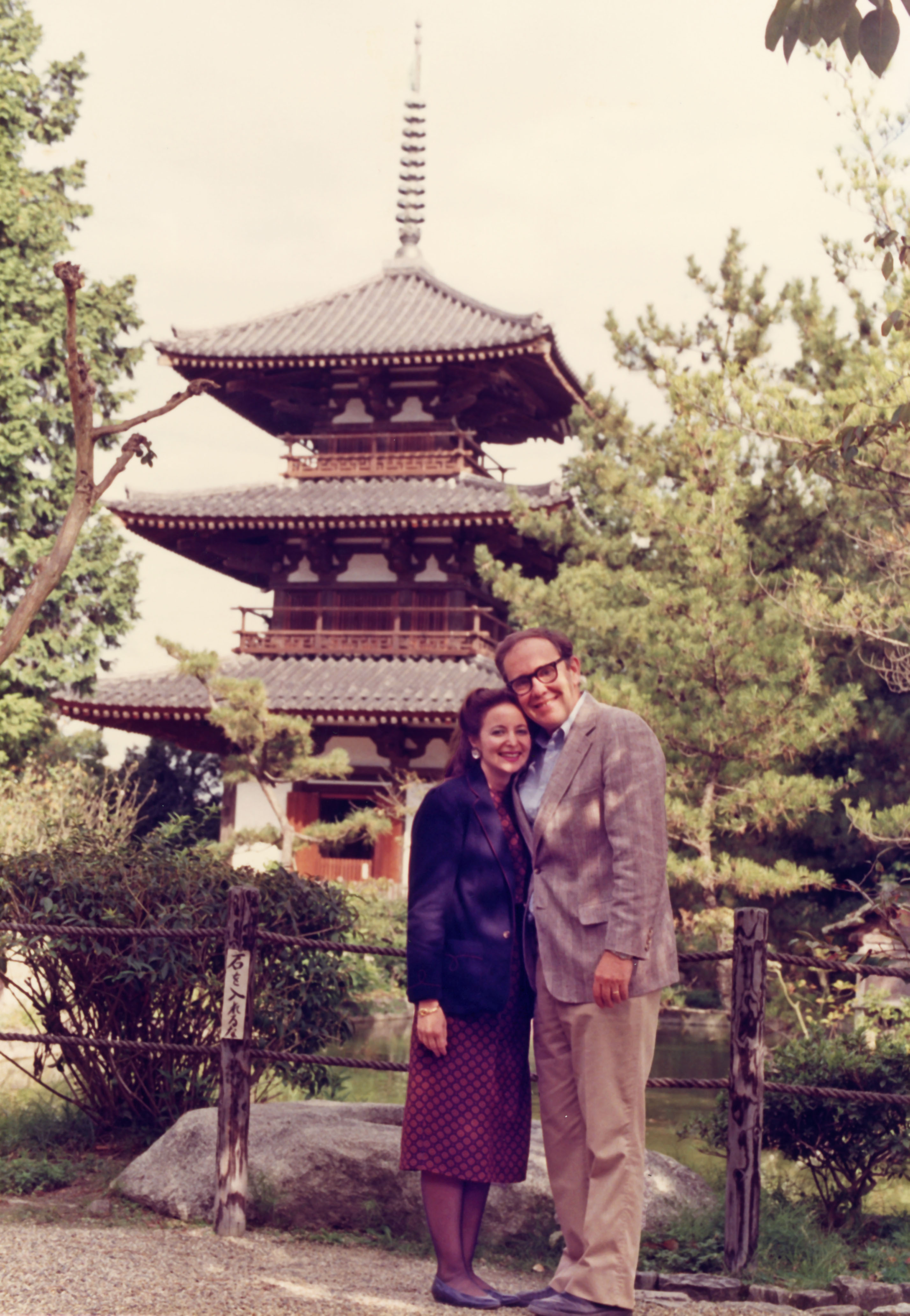

Fig. 3. Alice Yelen Gitter and Kurt Gitter on their honeymoon, in front of Yasaka-no-To pagoda, Kyoto, 1986.

These generous and deeply knowledgeable art dealers, from whom I had the privilege of learning, now define the history of Japanese art collecting in a bygone era: the Yabumoto brothers, Soshiro and Shogoro; the Yanagi family (fig. 2), Takashi, Koichi, and Shigehiko; the Mizutani family, Nizaburo, Ishinosuke, and Shoichiro; Daizaburo Tanaka; Mitsuru Tajima; Kenzaburo Marui; Yoshio Arimura; Joan Mirviss; Klaus Naumann; and Shibunkaku.

Our collection grew rapidly. Our first museum exhibition was in 1976. Zenga and Nanga: Paintings by Japanese Monks and Scholars, organized by the New Orleans Museum of Art and curated by the late Stephen Addiss, traveled to four other American museums. Japanese art was rarely featured in American museums at that time.

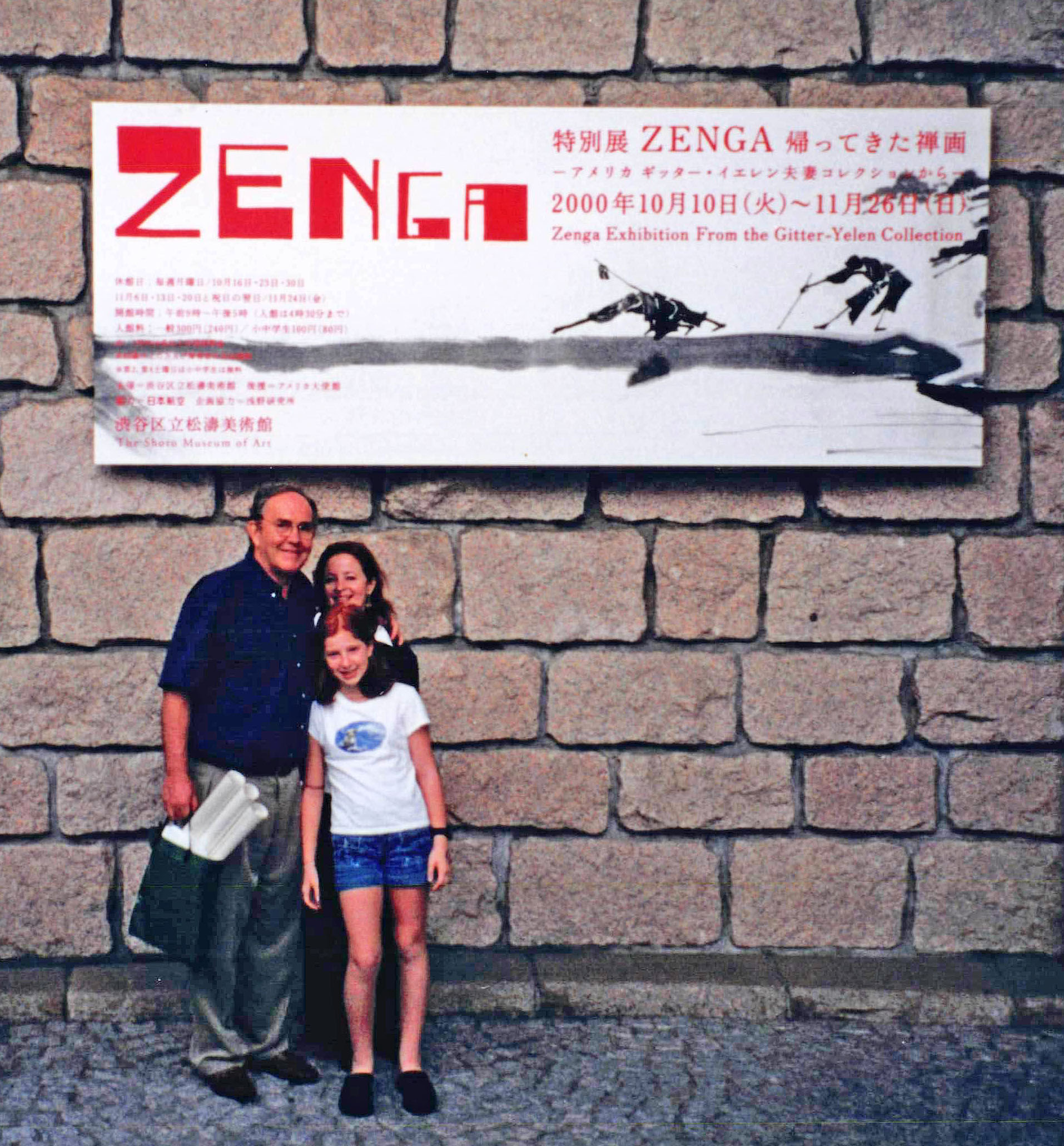

In 1986 I married Alice Yelen Gitter (fig. 3), and we continued to carve the path of our collection together. Our mutual interest in the arts—she as a curator/educator and I as a collector—has nourished and enriched our collection of Japanese art. Together, we have acquired many forms of Japanese art, including sculpture, Edo-period paintings from the schools of Nanga (literati painting), Zenga, Rinpa, Maruyama-Shijō, and Ukiyo-e, as well as contemporary ceramics. In our more than thirty-six years of marriage, exhibitions of our collection, some with a particular emphasis on Zenga, have been seen in multiple cities around the United States, and Zen exhibitions and catalogues containing our collection have been produced in Japan, Israel, and Australia, the latter two being held at their respective national museums. In 2000 Yuji Yamashita curated the first exhibition of our Zenga paintings (Zenga—The Return from America) (fig. 4) in Japan, which toured the country and encouraged viewers to understand this work as the imagery of talented painters rather than solely as religious expressions of their Zen faith.

Fig. 4. Kurt, Alice, and Manya-Jean in front of the exhibition sign for Zenga—The Return from America, curated by Yuji Yamashita, Shoto Museum of Art, Tokyo, 2000.

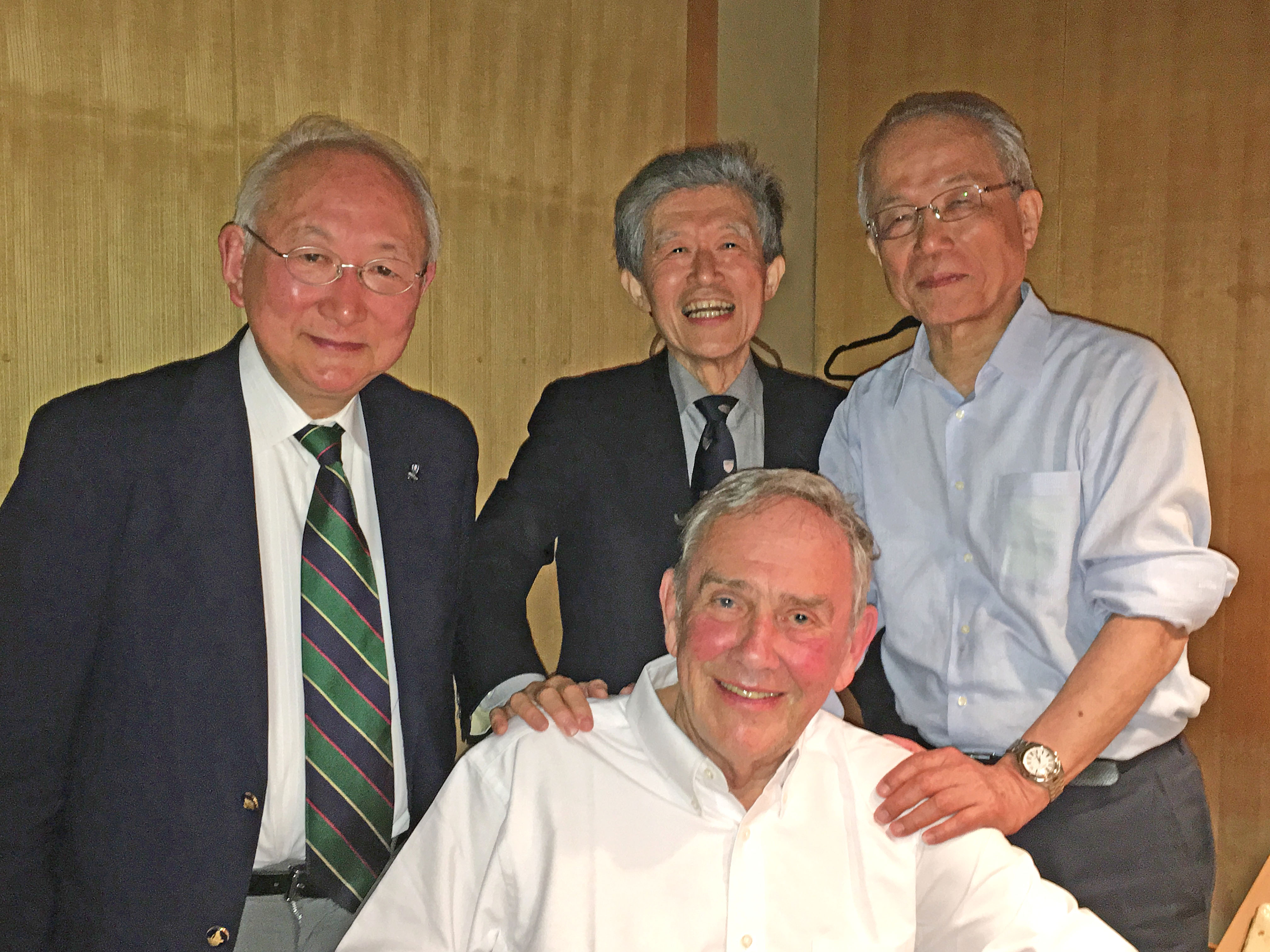

From the beginning, we have developed substantive friendships with burgeoning and eminent Japanese art scholars, which have lasted for decades and have provided great meaning to our lives. Among these are Sasaki and Masako Johei, Tadashi and Yasako Kobayashi, Motoaki Kono, Masatomo Kawai (fig. 5), Yukio Lippit, Matthew Welch, John Carpenter, Matthew McKelway, Anne and Sam Morse, Steve Addiss, and Andrew Watsky. While I have navigated my own path for seeking and studying artworks and always made my own collecting decisions, exchanging opinions and sharing enthusiasm with scholars on the works I was considering has increased our understanding and enriched our experience.

Long-term valued associations with numerous art museums have brought us immense satisfaction. These include: New Orleans Museum of Art (NOMA); National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian (previously Freer Gallery of Art), where I served on the board for ten years; the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Philadelphia Museum of Art; Princeton University Art Museum; and the Israel Museum, Jerusalem. From 1974 to the present, I have served on the board of the New Orleans Museum of Art, where I have actively encouraged the collection of Japanese art. John Bullard, NOMA director for over thirty-five years and a close friend, also became highly interested in this subject and traveled to Japan with us on numerous occasions. Our involvement with NOMA resulted in Japanese art becoming a major component of NOMA’s collection and mission, with a designated exhibition space and a curator, Lisa Rotondo-McCord, who is committed to this field. Over time, we have donated approximately four hundred works of Japanese art to various institutions around the world. Our interest has always been to share our artworks where they could be studied by scholars and seen by the public.

Fig. 5. Professors Masatomo Kawai, Tadashi Kobayashi, and Motoaki Kono, known as the “3 Ks,” with Kurt Gitter, Tokyo, 2016.

Fig. 6. The Gitter-Yelen Art Study Center, New Orleans, founded 1997.

In 1997 we formed the Gitter-Yelen Foundation and acquired another home adjacent to ours in New Orleans that serves as the Gitter-Yelen Art Study Center (fig. 6). Here, we store our Japanese art collection, and we have hosted more than a hundred scholars, including about forty from Japan, who stayed at the center while studying the collection in depth. We also developed a series of lectures by visiting scholars from various U.S. and international museums and universities for individually chosen groups of educators and enthusiasts, especially local art professionals and museum trustees, which often involves hands-on access to objects. Beyond the actual study center, we created and maintain a website, manyoancollection.org, and we were one of the first to provide online access to approximately one thousand works of Japanese art, both paintings and ceramics.

Fig. 7. Kurt at his 80th birthday celebration, with Alice (center) and children (top left to right) Ricky, Doug, Greg, Linda, and Manya-Jean, New Orleans, 2017.

Alice and I are proud to see this exhibition come to fruition under the talented guidance of Director Gary Tinterow, The Margaret Alkek Williams Chair of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and travel to the Japan Society in New York and the Israel Museum, Jerusalem. For more than sixty years, this richly creative artwork filled with strong individual expression has had a long-lasting and joyful impact on our lives (fig. 7). It is our hope that this exhibition and online catalogue will expose Japanese Zen painting to a new and broader audience while continuing to invite further scholarship and interpretation.

—Kurt A. Gitter, M.D.

Note: For a more detailed reflection on Kurt Gitter’s life of collecting and prior achievements, see “Reflections of a Collector,” originally published in Impressions, no. 39 (2018): 168–99, available online at http://www.jstor.org/stable/45201232.