- Patent Alarm Timepiece

- Lighthouse Clock

Explore Further

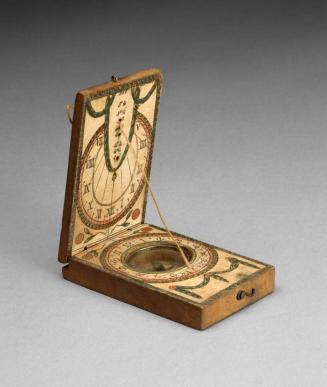

Clockmaker Simon Willard (1753–1848) of Roxbury, Massachusetts, is best known today for his “patent timepiece,” now often called the “banjo” clock by collectors, a design for which he received a patent in 1802. Willard’s use of the term “timepiece” indicates a movement that displays the time, but does not strike the hour. Building on a design he had created by 1780 for a small shelf clock, the banjo clock was an ingenious adaptation of an eight-day movement, more often seen in tall-case clocks, to a much smaller and more economical wall-mounted case, frequently embellished with colorful, gilded églomisé panels. These clocks, less expensive than tall-case clocks, became very popular and were copied, adapted, and manufactured by many other makers, only some of whom were licensed by Willard. Willard received another patent in 1819, his third and final, for an “alarum timepiece,” the form that is today referred to by collectors as the “lighthouse” clock. As the name indicates, the original design was for a clock with an alarm function. Contemporary advertisements indicate that Willard described these clocks as portable and easy to move from room to room.

Unlike the banjo clocks, the lighthouse clocks did not achieve commercial success. Though an exact number is not known, it is thought that some 200 lighthouse clocks were produced. The clocks’ configuration with glass dome-covered dials made them vulnerable to accidental damage. In addition, their heavy weights – necessary to allow the movement to run for eight days as they descended only a short distance – inside relatively small, freestanding cases reduced their stability. Despite Willard’s claims of easy portability, most owners probably recognized these clocks were safer if kept in one place.

Compared with the banjo clocks, the lighthouse clocks were significantly more costly to produce, certainly a factor in their greater rarity. Willard made lighthouse clocks with a surprisingly wide variety of case configurations and with variations in the movements as well. Some featured the alarm function, while others did not. Ornamentation, such as the type and quantity of applied gilt-brass mounts and bezels, also varied. Early versions of the form feature the dome-covered dial atop a rectangular box-form mahogany case. Soon the more typical case form emerged: a square, octagonal, or round plinth supporting a central columnar element surmounted by the dial and dome. Some of these were painted, some were clear-finished mahogany, and some were painted sheet iron. This lack of standardization may have allowed individual examples to meet the purchasers’ aesthetic requirements, but no doubt made economical manufacturing much more challenging.

Provenance[Auction of Van Dykes antiques, Worcester, Massachusetts, August 9, 1944]; purchased by Marcus A. Coolidge (1865–1947), Fitchburg, Massachusetts [1], through Mrs. E. H. Stafford; Helen Coolidge Woodring (1906–1986); Cooper Coolidge Woodring (1937–2021); given to the Kansas Governor’s Residence,Topeka, Kansas [2]; private collection, Cincinnati; purchased by MFAH, 2023.

[1] Former senator of Massachusetts

[2] Also known as Cedar Crest

Inscriptions, Signatures and Marks

Cataloguing data may change with further research.

If you have questions about this work of art or the MFAH Online Collection please contact us.