Hercules and Antaeus

Allison, Ann Hersey. “The bronzes of Pier Jacopo Alari-Bonacolsi, called Antico.” Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen in Wien 89–90 (1994): 148–51, no. 18C, Figs. 92, 96–97.

Avery, Charles, and Anthony Radcliffe, eds. Giambologna 1529–1608: Sculptor to the Medici. London: Art Council of Great Britain, 1978.

Bober, Phyllis Pray, and Ruth Rubinstein. Renaissance Artists and Antique Sculpture. A Handbook of Sources. 2nd ed. London: Harvey Miller Publishers, 2010.

Bresc-Bautier, Geneviève, Guilhem Scherf, and James David Draper, eds. Cast in Bronze: French Sculpture from Renaissance to Revolution. Paris: Musée du Louvre, 2009.

Chambers, David, and Jane Martineau, eds. Splendours of the Gonzaga. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, 1981, 136.

Di Lorenzo, Andrea, and Aldo Galli, eds. Antonio e Piero del Pollaiolo, “Nell’argento e nell’oro, in pittura e nel bronzo….” Milan: Skira, 2014.

Ferrari, Daniela. “L’Antico nelle fonti d’archivio.” In Bonacolsi l’Antico. Uno scultore nella Mantova di Andrea Mantegna e di Isabella d’Este, edited by Filippo Trevisani and Davide Gasparotto, 300–28. Milan: Electa, 2008.

Hiesinger, Kathryn Bloom. “Renaissance Bronzes in Houston.” Forum 9, no. 1 (Spring 1971): 75–76, fig. 3.

Leithe-Jasper, Manfred. “Herkules und Antaeus. Gedanken zur ‘Sfortuna’ einer einst vielbewunderten Antiken Skulptur.” In Das Modell in der bildenden Kunst des Mittelalters und der Neuzeit. Festschrift für Herbert Beck, edited by P.C. Bol, 139–53. Petersberg: Imhof, 2006.

Leithe-Jasper, Manfred, and Patricia Wengraf. European Bronzes from the Quentin Collection. New York: M.T. Train/Scala, 2004.

Luciano, Eleonora, Denise Allen, and Claudia Kryza-Gersch. Antico. The Golden Age of Renaissance Bronzes. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2011.

Madan, Falconer. The Gresleys of Drakelowe. An Account of the Family, and Notes of its connexions by Marriage and Descent from the Norman Conquest to the Present Day. Oxford: The William Salt Archaeological Society, 1899.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Catalogue of the Edith A. and Percy S. Straus Collection. Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1945, 36, no. 70.

Paolozzi Strozzi, Beatrice, and Dimitrios Zikos, eds. Giambologna, gli dei, gli eroi. Genesi e fortuna di uno stile europeo nella scultura. Florence: Giunti Editore, 2006.

Paton, W. R., trans. The Greek Anthology. 5 vols. London, 1916–18.

Planiscig, Leo. Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien: Die Bronzeplastiken, Statuetten, Reliefs, Geräte und Plaketten. Vienna: Schroll, 1924.

Planiscig, Leo. Piccoli Bronzi Italiani del Rinascimento. Milan: Treves, 1930.

Robinson, J.C., ed. Catalogue of the Special Exhibition of Works of Art of the Medieval, Renaissance, and more recent Periods, on loan at the South Kensington Museum, June 1862. London: Printed by George E. Eyre and William Spottiswoode for H.M.S.O., 1863.

Trevisani, Filippo, and Davide Gasparotto, eds. Bonacolsi l’Antico. Uno scultore nella Mantova di Andrea Mantegna e di Isabella d’Este. Milan: Electa, 2008, 216.

Warren, Jeremy. The Wallace Collection. Catalogue of Italian Sculpture. 2 vols. London: The Trustees of The Wallace Collection, 2016.

Wengraf, Patricia, ed. Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes from the Hill Collection. London: Holberton, 2014.

Wilson, Carolyn C. “Leo Planiscig and Percy Straus, 1929-1939: Collecting and Historiography.” In Small Bronzes in the Renaissance, edited by Debra Pincus, 247–74. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2001, 253–54, figs. 9–10.

Wright, Alison. The Pollaiuolo Brothers: The Arts of Florence and Rome. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005.

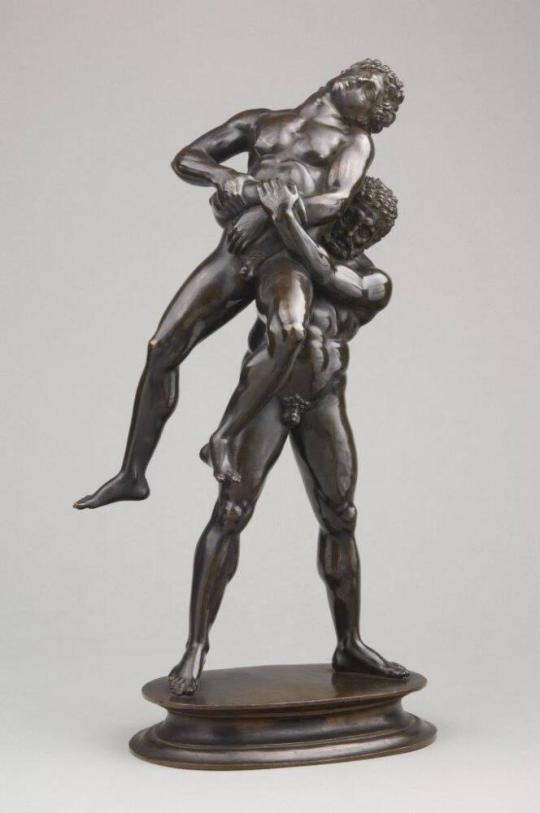

ProvenanceSir Robert Gresley (1866–1936), Drakelow Hall, Derbyshire; [Julius Goldschmidt, by October 1930]; bought by Percy S. Straus on January 9, 1931; bequeathed to MFAH, 1944.Hercules and the giant Antaeus, both naked, are shown wrestling. The bearded Hercules, his legs set apart, has gripped Antaeus from behind and lifts him bodily from the ground, holding both Antaeus’s hands pinned against his stomach. Hercules’s right foot slightly lifts from the ground, suggesting a surge of power as the giant is hauled upwards, while Antaeus screams in pain as his breath is crushed out of him. The bronze is a rough and very heavy cast; there are flash lines from the molds in which the model was formed, for example on Hercules’s buttocks. It was never cleaned up following casting, so the sprue remains, now forming a rough base. There are four intact sprue trees connecting the base and the figure group, while another, once connected with Antaeus’s feet, has been broken off. The surface is unworked and is now covered in a thick lacquer. The bronze was the subject of a hand-held x-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (xrf) examination undertaken by Dylan Smith of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, in August 2012. This examination established that the sculpture is a leaded medium tin bronze, with significant zinc and antinomy, and other trace elements. An unusually high iron reading was recorded, suggesting that the figure probably has some form of coating containing iron on its surface.1

The story of Hercules’s defeat of Antaeus is a parergon or “by-labor” of the tenth of Hercules’s Labors, the stealing of the oxen of Geryon (or, depending on the source, the eleventh, the stealing of the apples from the garden of the Hesperides). Antaeus was a giant king of Libya, the son of Neptune and of Gaia, the earth goddess. He derived his enormous strength from his mother, thus so long as he remained in contact with mother earth, he could not be defeated. However, if he could be lifted from the ground, his strength would evaporate. Antaeus challenged all passers-by to wrestling matches and, having killed his opponents, collected their skulls to use to roof a temple to his father. The hero and demigod Hercules came across Antaeus and, like other passers-by, was challenged to combat. Hercules quickly found he could not defeat the giant, whose strength was constantly refreshed from the earth. Having, however, realised the secret of his power, Hercules lifted Antaeus up bodily and, unable to use his hands to wield a weapon or deliver a physical blow, instead cracked the giant’s ribs, suffocating him.

The combat between the giants became one of the classic demonstrations of the strength of the giant Hercules and his ability to find clever ways to defeat enemies who at first appeared invincible. Its attraction for Renaissance painters and sculptors, for whom it became a popular subject in the decades around 1500, lay in the opportunity it provided to depict the interaction between two powerful nude bodies. In addition to the model by the Mantuan sculptor Antico, of which the Straus group is a cast, other important small bronze versions from the Renaissance period are those made in Florence, a city that claimed a special association with Hercules, by Antonio Pollaiuolo (1431–1498),2 and by Giambologna (1529–1608).3 Educated Renaissance men and women in Florence, Mantua, and elsewhere would have been deeply familiar with the legends of Hercules and other classical literary descriptions, such as an anonymous epigram from Maximus Planudes’s anthology of Greek poems and epigrams, which remains a powerful comment on the power of a bronze group to convey pity: “Who made this groaning bronze? Who with their art / created such agony of expression and daring? The statue breathes. I pity [Antaeus] in his toil / and bristle at the strong, daring Herakles / for he holds Antaeus struggling from the wrestling / and Antaeus is bent double and seems to let out a scream.”4

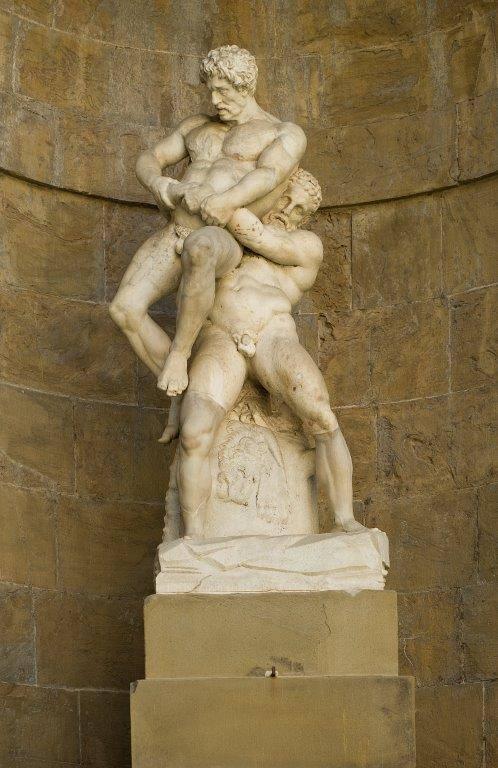

Antico’s Hercules and Antaeus differs from the versions of the subject by Pollaiuolo and Giambologna, in that Hercules grasps Antaeus from behind. The source for his model was a Roman copy of a Hellenistic marble torso, which was first certainly recorded in 1503 in the Belvedere in Rome, but seems to have been known before that to artists, including Mantegna.5 At this time the torso was in a fragmentary state but was nevertheless greatly admired, Antico describing it to his patron Isabella d’Este as “the most beautiful antiquity in existence.”6 In 1560 Pope Pius IV presented the sculpture to Cosimo I de’ Medici. After its arrival in Florence, it was restored with, in particular, the addition of arms and a head for Antaeus, and legs for Hercules. By 1568 it had been installed in the courtyard of the Palazzo Pitti, where it remains to this day.

There is a small group of bronze statuettes based on this famous antiquity, including a vigorous model known in a number of casts,7 and another bronze group formerly in the Eissler collection, Vienna.8 There are also two prime casts of Antico’s model, in the Victoria & Albert Museum, London,9 and in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.10 The earlier London version was one of a number of bronze models created by Antico for his patron Bishop Ludovico Gonzaga (1460–1511); it is generally thought to have been made around 1500, although it has been suggested that the head of Antaeus, which is the sculptor’s invention, reflects the great antique sculpture of Laocoön, discovered in Rome in 1506. The Vienna version was made some years later, in around 1519, one of a number of bronze casts Antico had made from his old models, at the request of Isabella d’Este, Marchioness of Mantua. The cast bears on the underside of the original base the cast-in inscription “D[IVA] ISABELLA M[ANTVA]E MAR[CHIONISSA],” or “The Divine Isabella, Marchioness of Mantua.” There are quite substantial differences in details and finish between the two versions: in the London version, for example, the eyes of the protagonists are silvered; the expressions of the struggling Antaeus are quite different in the two versions, as is his hair; the pubic hair is flat at the top in London, whereas it rises to a triangular point in Vienna.

The Houston version is an aftercast, a cast made from molds taken from a finished sculpture. Aftercasts are generally blunter in their details than the original model, and are always a little smaller, since the molten metal shrinks on cooling. The differences between the London and Vienna versions of Antico’s model make it relatively easy to confirm that the Houston version was cast from the later version now in Vienna. We can only speculate when the aftercast might have been made. The original bronze probably came to London with the purchase by King Charles I of the Gonzaga collections in the late 1620s. If so, although it does not appear in the extant records for the sales, it is likely to have been sold by the Commonwealth authorities along with most of the former royal collections after the king’s execution in 1649. The Habsburg Archduke Leopold Wilhelm, in whose collection the bronze is first recorded in 1659, bought heavily from the Commonwealth sales. Ann Allison suggested that the cast might have been made in England, during the Commonwealth period and before the bronze had found its way to Brussels. This assumption is unprovable, but might help explain why the group was to be found in an English collection in the early twentieth century.

The cast is not especially skillful and has some serious flaws, such as the left eye of Antaeus, which is depressed. It is an extremely heavy cast, suggesting that large parts of the interior must be effectively solid cast.11 Why it was left in such an unfinished state is a mystery. Although this almost certainly would not have been the intention of the founder who left it thus, much of its interest today lies in its rarity as an historic bronze retaining evidence of its casting sprues. The best-known example of this phenomenon is a small bronze reduction after Martin van den Bogaert’s equestrian statue of king Louis XIV, which retains its entire network of sprues and vents.12 This extraordinary bronze was bought in 1754 in Paris by the Danish Ambassador, to help the French sculptor Jacques Saly, then engaged in Copenhagen on an equestrian statue of king Frederik V, as a guide for the placement of the sprues and vents. The sprues are much less complex in the Houston Hercules and Antaeus; perhaps it was thought easier simply to make a base around the sprues, as is indeed the case today.

This was precisely the solution recommended by Leo Planiscig in the second of two letters to the dealer Julius Goldschmidt, who had bought the bronze directly from Sir Robert Gresley in 1930. Goldschmidt had the bronze shown to Planiscig, although it is not certain that Planiscig ever saw the actual object, rather than simply photographs. In his first letter, of October 30, 1930, Planiscig identified the model, relating it to Antico’s cast in Vienna and asked Goldschmidt for a photograph. The photograph sent to Planiscig a couple of days later must have shown the bronze with its sprues, which Goldschmidt had assumed was the original socle. Planiscig replied on November 4, explaining what the sprues signified and emphasising that “they must not be removed” (“sie dürfen nicht entfernt werden”). He then suggested building a tabernacle-like base around them. Goldschmidt subsequently brought the bronze to New York, offering, in a letter of January 8, 1931 to Mrs. Straus, “a very great piece of the Cinquecento” for a price of $7,000. A deal was struck the next day for the bronze at the price of $6,000.

It would appear therefore that the bronze must have been without any form of additional socle when it was bought by Julius Goldschmidt from Sir Robert Gresley. The Gresleys were an ancient English family with Norman origins, which had its main seat at the Elizabethan Drakelowe Hall, Derbyshire.13 Drakelowe and its collections were sold by Sir Robert Gresley in 1931, and the house was demolished in 1934. The most active collector within the family in the nineteenth century appears to have been Sir Thomas Gresley (1832–1868),14 who assembled before his early death a fine collection of Italian Renaissance medals and plaquettes, much of which he lent to the 1862 South Kensington Museum Loan exhibition,15 and which was sold a few years after his death.16

—Jeremy Warren

Notes

1. Average readings of the main component elements: copper (Cu) 77.5%; tin (Sn) 9.8%; lead (Pb) 6.2%; zinc (Zn) 2.4%; iron (Fe) 1.7%; antimony (1.6%). Trace elements of nickel, arsenic and silver. Report by Dylan Smith, National Gallery of Art, August 24, 2012.

2. Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Inv. 280B. Alison Wright, The Pollaiuolo Brothers: The Arts of Florence and Rome (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005), 335–40, figs. 270–74; Andrea Di Lorenzo and Aldo Galli, eds., Antonio e Piero del Pollaiolo, “Nell’argento e nell’oro, in pittura e nel bronzo…” (Milan: Skira,, 2014), 198–201, no. 13.

3. The finest cast, recorded in the collection of the Emperor Rudolf II, is in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, inv. KK 5845. Leo Planiscig, Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien: Die Bronzeplastiken, Statuetten, Reliefs, Geräte und Plaketten (Vienna: Schroll, 1924), 156–57, no. 260; Charles Avery and Anthony Radcliffe, eds., Giambologna 1529–1608: Sculptor to the Medici (London: Art Council of Great Britain, 1978), 132–33, no. 87; Beatrice Paolozzi Strozzi and Dimitrios Zikos, eds., Giambologna, gli dei, gli eroi. Genesi e fortuna di uno stile europeo nella scultura (Florence: Giunti Editore, 2006), 176–77, no. 9. For recent discussion and a list of versions, see also Jeremy Warren, The Wallace Collection. Catalogue of Italian Sculpture (London: The Trustees of The Wallace Collection, 2016), 2: 474–79, no. 108.

4. W.R. Paton, trans., The Greek Anthology (London,1916–18), 5:213, no. 97.

5. For the history of the statue, see Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny, Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Classical Sculpture 1500–1900 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981), 232–34, no. 47; Manfred Leithe-Jasper, “Herkules und Antaeus. Gedanken zur ‘Sfortuna’ einer einst vielbewunderten Antiken Skulptur,” in Das Modell in der bildenden Kunst des Mittelalters und der Neuzeit. Festschrift für Herbert Beck, ed. P.C. Bol (Petersberg: Imhof, 2006), 188–89, no. 137.

6. “l’Ercole che amaza Anteo, ch’è la più bella antigità che li fusse.” From a letter of April 1519 to Isabella d’Este. Daniela Ferrari, “L’Antico nelle fonti d’archivio,” in Bonacolsi l’Antico. Uno scultore nella Mantova di Andrea Mantegna e di Isabella d’Este, eds. Filippo Trevisani and Davide Gasparotto (Milan: Electa, 2008), 317–18, doc. 86.

7. For the cast in the Quentin collection and a detailed discussion of the model, see Manfred Leithe-Jasper and Patricia Wengraf, European Bronzes from the Quentin Collection (New York: M.T. Train/Scala, 2004), 54–67, no. 1. For the cast in the Hill collection, where it is attributed to Maso Finiguerra, see Patricia Wengraf, ed., Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes from the Hill Collection (London: Holberton, 2014), 90–99, no. 3.

8. Attributed by Leo Planiscig to a Florentine workshop, c. 1550. Leo Planiscig, Piccoli Bronzi Italiani del Rinascimento (Milan: Treves, 1930), tav. 194, fig. 336.

9. Inv. A.37-1956. Ann Hersey Allison, “The bronzes of Pier Jacopo Alari-Bonacolsi, called Antico,” Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen in Wien 89–90 (1994): 138–42, no. 18 A, figs. 82, 83, 90, 93; Filippo Trevisani and Davide Gasparotto, eds., Bonacolsi l’Antico. Uno scultore nella Mantova di Andrea Mantegna e di Isabella d’Este (Milan: Electa, 2008), 216–17, no. 5.10; Eleonora Luciano, Denise Allen, and Claudia Kryza-Gersch, Antico. The Golden Age of Renaissance Bronzes (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2011), 118, pl. 43.

10. Inv. KK 5767. Planiscig, Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, 54–55, no. 98; Allison, “The bronzes of Pier Jacopo Alari-Bonacolsi,” 142–48, no. 18 B; Trevisani and Gasparotto, Bonacolsi l’Antico, 236–37, no. 6.11; Luciano, Allen and Kryza-Gersch, Antico. The Golden Age, 119–20, pls. 44–45.

11. Solid casts, with the model made of solid wax with no core, are usually limited to small figures both because of the cost of the metal and the difficulty of successfully casting larger figures solid. Most bronze sculptures are otherwise made from a core over which a thin layer of wax is applied; it is this layer of wax, between the inner core and the outer vestment, that when heated and drained, provides the space filled by the molten metal.

12. Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen, Inv. KMS 5403. Geneviève Bresc-Bautier, Guilhem Scherf, and James David Draper, eds., Cast in Bronze: French Sculpture from Renaissance to Revolution (Paris: Musée du Louvre, 2009), 318–21, no. 88 B.

13. For the Gresleys, see Falconer Madan, The Gresleys of Drakelowe. An Account of the Family, and Notes of its connexions by Marriage and Descent from the Norman Conquest to the Present Day (Oxford: The William Salt Archaeological Society, 1899).

14. Madan, The Gresleys of Drakelowe, 131–33.

15. J.C. Robinson, ed., Catalogue of the Special Exhibition of Works of Art of the Medieval, Renaissance, and more recent Periods, on loan at the South Kensington Museum, June 1862 (London: Printed by George E. Eyre and William Spottiswoode for H.M.S.O., 1863), 34, nos. 556–671.

16. Catalogue of the Collection of Italian Bronze Medals, and Chasings in Relief, of the late Sur Thomas Gresley, Bart., Christie’s, London, July 5, 1871.

Comparative Images

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has made every effort to contact all copyright holders for images and objects reproduced in this online catalogue. If proper acknowledgment has not been made, please contact the Museum.