Introduction

The donation of an exceptionally fine collection of Italian Renaissance paintings and sculptures as well as works from the Northern school, and several English and French works, was made to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in 1941 in the names of both Edith Abraham and Percy Selden Straus, Sr. (figs. 1, 2). However, it was principally Percy S. Straus’s passion for art that is reflected in what was one of the finest private collections of European art assiduously assembled in America in the 1920s and 1930s. Although Straus’s earliest acquisitions were English eighteenth- and nineteenth-century paintings, his great love was Italian Renaissance paintings and sculptures. Indeed, he was quite a Renaissance man himself.

Fig. 1. Percy Selden Straus, 1876 –1944. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Archives.

Fig. 2. Edith Abraham Straus, 1882–1957. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Archives.

The Straus Family and Business

Scion of a wealthy New York merchant family and Harvard educated, Percy S. Straus was a highly successful businessman, generous philanthropist, fine sportsman, and exceptional art connoisseur and collector. He was the second son of Isidor Straus and Ida Straus, born June 24, 1876. Although on his birth certificate his name is given as P. Salomon Straus, he changed his middle name to Selden while still a teenager. Percy belonged to the first generation of his family born in the United States. His father, Isidor, was born in 1845 in Otterberg, a small town near Kaiserslautern in Rhineland-Palatine, Germany; he was nine years old when his mother set out with her four children to join her husband, Lazarus Straus in America. Lazarus Straus, born in 1819 into a Jewish family of grain merchants and landowners, had made his way to Georgia in the aftermath of the revolution of 1848, hoping for a better life. Upon his arrival in 1852, Lazarus started to work as a pushcart peddler, serving the far-flung plantations near the small settlement of Talbotton. He was so successful that he was able to open a store in the town in 1854 and to arrange for his wife and children to emigrate from Germany. His growing business was hard hit by the Civil War and the prognosis of an improvement in the economic situation in the South seemed so uncertain that Lazarus, apparently on the advice of his son Isidor, who had been working from Europe during the war, moved the family to New York in 1865.

From an early age, Isidor was a remarkably shrewd businessman, who together with his father and his brother Nathan was responsible for the phenomenal success of the family business. In 1874, they rented a 25 x 100-foot space on the bottom floor of the R. H. Macy & Co. department store, where they sold china wares and crockery. By 1888 they were partners in the firm, and in 1895 its ownership was transferred to Isidor and Nathan Straus. In a remarkable American success story—through hard work, thrift, and skill—the Straus family rose within forty-three years from pushcart peddling to owning what would become known as the largest store in the world.

Family was always of utmost importance to Isidor: he was a devoted husband to Rosalie Ida Blun, whom he married in 1871, and an equally steadfast father to their children, Jesse Isidor, Percy Selden, Sara, Minnie, Herbert Nathan, and Vivian. His growing wealth enabled Isidor to afford the finest education for his children, culminating in all three sons attending Harvard University. Percy, upon graduating from Harvard in 1897, joined the family firm, but in 1898 he went to Istanbul as private secretary to his uncle Oscar, who was serving as the American minister to the Ottoman Empire. Percy contemplated a similar diplomatic career but returned to New York after one year to join his father, uncle, and brothers in the management of Macy’s. His marriage in 1902 to Edith Abraham, daughter of Abraham, further consolidated their families’ business partnership in the Brooklyn-based department store Abraham & Straus.

Fig. 3. Percy and Edith Straus with their family in their Park Avenue apartment. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Archives.

During the following decades, Percy devoted himself to the family business, rising to company president and chairman of the board. He was, according to his New York Times obituary, “largely responsible for the tremendous latter-day development of the mercantile establishment.”1 Percy and Edith were blessed with three sons, Ralph Isidor (born 1903) and Percy Selden (born 1906), followed ten years later by Donald (born 1916) (fig. 3). In 1912, however, tragedy struck the family when Percy’s parents, Isidor and Ida, lost their lives in the Titanic disaster. In 1904 Isidor laid out the disposition of his will in a letter to his sons, leaving to them his “entire interest in all business enterprises.” Legacies to his wife and daughters, generous endowments to various charities, and gifts to servants are specified, but there is no reference to an art collection.2 He did not mentioned it in his will filed in 1909, nor did he refer to any collecting activities in his autobiography, written in 1911.3 Although Isidor and Ida Straus are identified as collectors of medieval and Renaissance art in Joan Adler’s 2014 article “Strauses and the Arts,” the only specific work cited is the plaster cast by Antonio Canova of his celebrated Cupid and Psyche (1794), which Isidor acquired in 1905 and donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.4 However, a small number of receipts in the Straus Society Historical Archives provide what must be a snapshot view of Isidor’s collecting activity.5 They reveal that from 1885 to 1887 he bought several works by Old Masters, including Peter Paul Rubens, Gerard Dou, and Titian, as well numerous paintings by nineteenth-century artists such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Franz von Defregger, Johann Peter Hasenclever, and W. R. Richards, from the New York auction house Thomas Kirby. Furthermore, he acquired entire collections, such as the George Whitney collection of paintings for $892.50 in 1885, the collection of Beriah Wall and John Brown, between March and April 1886 for $1,155, and paintings from the Aspinwall Gallery on April 6, 1886, for $2,230, and from the A.T. Stewart collection in March 1887 for $2,200. Even for a man of his considerable wealth, these were significant amounts. This very limited documentary evidence, of course, does not preclude a more extensive collecting activity, but it will take further research to establish the extent of Isidor’s collection and the present whereabouts of its works of art.

Building the Collection

None of the works in the Edith A. and Percy S. Straus Collection bequeathed to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, had been inherited from the parental collection. Because the documentary material—receipts, scholarly expertises, extensive correspondence with dealers and two collection books specifying the installation of the works the residence—was given to the Museum by Percy’s brother Ralph I. Straus in 1972, we are able to paint a clear picture of Percy Straus’s collection activity. According to these, his collecting began in 1917, yet there is evidence that he had already assembled a significant collection earlier, which seems to have been lost when his country house in Middletown, New Jersey, was completely destroyed by fire in 1915. Newspaper reports of the tragedy mention the loss of tapestries and other works of art, but without giving any specifics.6 Straus did not rebuild the home, but instead bought Hilholme, an estate in Port Chester, Westchester County, New York, in 1925. However, from the Straus collection books now in the archives of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, we know that the collection that was later bequeathed to the museum was not displayed there, but in Straus’s primary New York City residence, a luxurious apartment at 875 Park Avenue in Manhattan. Consummate businessman that he was, Straus carefully kept records of his purchases. In most cases, the date and the name of the dealer or auction house are documented for each acquisition, and for many also the price. Copious correspondence, not just with the dealers but also with the most knowledgeable art historians, such as Bernard Berenson, Max Friedländer, Richard Offner, and Leo Planiscig, whose opinions Straus sought, is preserved as well. It becomes evident that Straus was an exemplary collector: thoughtful, cultured, and scholarly, with a sharp eye for quality and with a merchant’s keen sense of a fair price, who commanded ample financial means to support his passion. The Strauses traveled to Europe frequently, to see and buy art, but they also bought from dealers in New York. Some of those purchases were made by Edith, but her activity was limited by poor health.

The collection falls into five parts: Italian pre-Renaissance and Renaissance paintings, Northern European Renaissance paintings, eighteenth- and nineteenth-century English and French paintings, Italian and French sculptures, and a small number of works on paper. Making up nearly half of the paintings and two-thirds of the sculptures in the collection are the Italian pre-Renaissance and Renaissance works, a clear indication of Straus’s predilection for this period. Whereas the bronzes mostly represent mythological figures, the Italian paintings, except for three portraits and one mythological scene, depict Christian religious subjects, with a heavy emphasis on the image of the Virgin and Child. Given the period of their creation this is not surprising; however, it is notable that Straus, who came from a Jewish family, did not shy away from these subjects. One reason for his attitude may be found in an upbringing free from religious affiliations, for which his father took full responsibility.7 But perhaps his desire to acquire works from the period most highly esteemed at the time was equally profound. Having carefully ascertained authentications from the foremost scholars, Straus bought works by the most renowned artists, including Fra Angelico, Giovanni Bellini, Michelangelo, Rogier van der Weyden, Hans Memling, and Albrecht Dürer, but he was also willing to buy works by lesser-known and even unknown artists. As is the case in most collections, some works have been reattributed over the years; nonetheless, the quality of collection remains remarkable. For Straus, quality and exceptional condition clearly outweighed a famous name.

The earliest acquisition, dating to 1917, was not a Renaissance painting, but an early nineteenth-century English portrait attributed at the time to John Opie (cat. 50, 44.525). It was followed two years later by portraits by Sir Joshua Reynolds (cat. 47, 44.527) and Henry Raeburn (cat. 48, 44.526) and by a small landscape from the School of John Crome (cat. 49, 44.524), but no further English works came into the collection for the next decade. During the 1920s, Straus concentrated almost exclusively on Italian art. A major early purchase was a Madonna and Child by Giovanni Bellini (cat. 14, 44.552), the Venetian Renaissance artist renowned for this genre. After much contemplation and correspondence, Straus bought it through F. Mason Perkins in 1922, but it remains unclear whether he realized the extent of restoration the figures had undergone. Many scholars at the time accepted it as an autograph work, but the attribution was and continues to be controversial. Of indisputable quality are two images of the Virgin and Child by the Master of the Sienese Straus Madonna (cat. 1, 44.564) and the Master of the Straus Madonna (cat. 8, 44.565), anonymous masters named after the Straus Collection where their masterpieces reside, acquired in 1923 and 1926, respectively. In regard to the work by the Master of the Straus Madonna, Richard Offner wrote to Straus that he had known and loved this painting for fourteen years and highly recommended its acquisition. Scholars have long believed that this extremely talented painter, whose works are technically refined and deeply moving, had been the teacher of Fra Angelico. Indeed, recent research not only supports this supposition but furthermore suggests that his name was Ambrogio di Baldese, about whom little is known, but who must have been a key figure at the watershed moment of Florentine painting at the end of the medieval period and the beginning of the Renaissance movement.

Throughout the 1920s, Straus acquired slowly, one or two works per year, but in 1925 and in 1929 he bought copiously. The nine works acquired in 1925 are all Italian Renaissance paintings, whereas of the twelve works bought in 1929, eight are sculptures and two are important Northern paintings, including the Fall of Man, 1549, by Lucas Cranach the Younger (cat. 32, 44.546). This last work, purchased from Vitale Bloch, Berlin, together with the drawing after the painting by the same artist, is an art historically important acquisition. Seen together, they confirm the earliest dated painting by Lucas Cranach the Younger, whose previous works are entirely subsumed in the workshop output of his famous father, Lucas Cranach the Elder. Straus was circumspect in ascertaining the painting’s authenticity from Max Friedländer, the foremost authority on Northern paintings at the time. The bronzes came mainly from the foremost dealers in decorative arts, Jacques and Arnold Seligmann. Many of them, including the Bound Satyr (cat. 48, 44.594) as well as the three small plaques by followers and associates of Riccio (cat. 44–57, 44.593, 44.585, 44.596), are outstanding, but the exquisite Madonna and Child by Antonio Susini (cat. 60, 44.586) must be considered the most remarkable of the group. It is close in style to Giambologna, in whose workshop Susini worked for twenty years, but documents prove that this work with its sensitive modeling and tender expression, was Susini’s own invention.

The tempo of Straus’s acquisitions increased during the 1930, as multiple works entered the collection each year. Straus added significant Italian paintings, such as the small but important predella by Fra Angelico (cat. 10, 44.550), and the superb tondo by an unknown Ferrarese master, a desco da parto or birth tray depicting, in enchanting detail and with a stunning mastery of perspective drawing, the Meeting of Salomon and the Queen of Sheba (cat. 15, 44.574). He also delved deeper into the works of Northern Renaissance artists by acquiring a Madonna and Child by Rogier van der Weyden (cat. 23, 44.535) and the Portrait of an Old Woman by Hans Memling (cat. 24, 44.530), whose pendant is part of the collection of the Metropolitan Museum Art. At the same time that he was developing a taste for Northern paintings, Straus also made some remarkable purchases in Flemish sculpture. Among them, the early fifteenth-century ivory figure of God the Father, possibly from the School of Claus Sluter, is one of the finest of its kind (cat. 69, 44.581). Originally part of a Holy Trinity made for private devotion, this small work is characterized by translucent drapery of superlative handling. It is rivaled in finesse and elegance only by the large bronze plaque of Hercules Resting after the Battle with the Nemean Lion by the renowned Lombard master known as Antico (cat. 52, 44.582), which Straus had added to his already distinguished collection of small Italian Renaissance bronzes a year earlier.

Despite Straus’s conscientious and extensive efforts to ascertain the authenticity of works offered to him, occasionally he was misled. Thus, the Bust of a Young Woman, once thought to have been the Portrait of Simonetta Vespicci by Sandro Botticelli, is now attributed to Raffaellino del Garbo (cat. 17, 44.554), while the small plaster figure of Day, believed to have been the working model for the figure of Michelangelo’s Medici tomb was recognized as a copy by Johan Gregor van der Schardt, made during Michelangelo’s lifetime (cat. 66, 44.584). This would doubtless have been a great disappointment to Straus, who purchased it for a high price, trusting Leo Planiscig, who had advised him so astutely for many years.

Not having acquired any English works throughout the 1920s, in the early 1930s Straus added the important portrait of Charles Louis, Elector Palatine by Anthony van Dyck (cat. 36, 44.532) to this group as well as small circular portrait of Sir Henry Guildford, a decorative work likely to have come from Hans Holbein the Younger’s workshop (cat. 30, 44.549). Other more decorative eighteenth-century French works, including a charming Pastoral Concert by Jean-Baptiste Pater (cat. 41, 44.544) and the portrait of a Little Boy of the Comminges Family, attributed to Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun at the time (cat. 43, 44.537), as well as two light-hearted sculptures of infant satyrs by Clodion (cat. 73, 44.576, 44577) and Jean-Antoine Houdon’s lovely bust of his two-year-old daughter Anne-Ange (cat. 75, 44.578) were acquired between 1932 and 1937. Last but not least, the superb engraving of Saint Eustace by Albrecht Dürer (cat. 26, 44.548), added in 1936, should be regarded as representative of the small collection of works on paper. It testifies to Straus’s sophisticated taste as well as to his unceasing demand of the highest quality in all mediums.

The Collection in the Straus Home

All of the paintings in the Straus Collection were displayed in Edith and Percy Straus’s New York apartment prior to the donation of the collection to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.8 Percy and Edith moved to 875 Park Avenue in 1912. Pease & Elliman, the building’s representatives, published four floorplans for 875 Park Avenue, each containing a library, parlor, dining room, foyer, and kitchen.9 The main difference between the floorplans is the number of bedrooms, ranging from two to four. The Strauses lived on the ninth floor, which featured a fifth, unpublished floorplan.10 Without documentation of the precise plan of the Strauses’ apartment, conjecture is necessary for determining the probable layout. The Strauses paid the building’s highest known rental fee in 1912, which suggest that the Strauses’ apartment consisted of perhaps ten rooms and three bathrooms.

A binder noting the paintings of the Straus Collection as displayed in the family’s home, with sections devoted to individual rooms, is preserved in the archives of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.11 Presumably, the binder reflects the final arrangement of artwork, prior to Percy’s death and the removal of the collection to Houston.

As documented in the binder, the entrance hall or foyer contained disparate works. Four of the objects, purchased together in 1925, represent the saints Bartholomew, Agnes, Elizabeth of Hungary, and Nicholas of Bari from an altarpiece by Andrea da Firenze. The hall also displayed the portrait by the Flemish painter Cornelis de Vos and the painting by Fungai.

The section in the binder designated as the music room notes twelve works. The Strauses’ finest Italian gold-ground paintings were assembled here, including the works by the Master of the Straus Madonna (cat. 8, 44.565) and the Master of the Sienese Straus Madonna (cat. 1, 44.564). As it featured such a remarkable and dramatic set of paintings, it seems that the room also served as a picture gallery. The music room opens directly onto the foyer; thus visitors would likely have easy access to the room upon entering the apartment. The impact of seeing all twelve works in one room would have been profound. The art historian Creighton Gilbert, who studied under Straus’s advisor Richard Offner, recalls seeing the Fra Angelico panel (cat. 10, 44.550) displayed on the grand piano, “resting in a sheet-music holder.”12 This is one of the few specific references to where and how the Strauses displayed the collection in their home.

The dining room section of the collection binder notes only four works, all portraits, including their Sir Anthony Van Dyck (cat. 36, 44.532), Sir Joshua Reynolds (cat. 47, 44.527), and after Sir Henry Raeburn (cat. 48, 44.526. This approach is reminiscent of great English country homes such as Chatsworth and Petworth, which feature portraiture in the dining room.13 Americans of this period embraced the model. For example, art collector Henry Clay Frick also featured British portraits in the dining room in his newly built mansion on Fifth Avenue.14

The binder’s section for the boudoir lists nine predominantly eighteenth-century French works. Relatively small in scale but of high quality, they included Jean-Baptiste Pater’s Pastoral Concert (cat. 41, 44.544) and a portrait of a child by Marie-Elisabeth Lemoine (cat. 43, 44.537). It is presumed that the boudoir was used as Edith’s private space and was furnished in the French Rococo style, much like her room at Hilholme, the Strauses’ country house in Port Chester, New York. It may have held the eighteenth-century French sculptures by Clodion and Houdon as well.

As chairman of R. H. Macy & Co., Percy Straus had his business office at corporate headquarters; therefore, this study could be directed exclusively towards his personal interests. Percy approached his art collection and the collecting process as a scholar. In the study were two works on paper: the superb Dürer engraving of Saint Eustace, and a fine seventeenth century portrait drawing of an old man, as well as a small English landscape in oil. Although not documented in the binder, other works that may have been installed in the study include Sir Henry Guildford now attributed to the circle of Hans Holbein the Younger(cat. 30, 44.549), two works by Lucas Cranach the Younger (cats. 32 and 33, 44.546 and 44.547), and the three small Corneille de Lyon portraits (cats. 37–39, 44.538–540), as well as the fine collection of Renaissance bronzes, appropriate for a humanist’s study.

The remaining twenty-one works in the Straus Collection are not contained in the binder; however, we may suppose that many of these paintings were hung together in the parlor, which the Strauses used as a drawing room. Two different references support this deduction: first, the family photograph of Edith, Percy and their extended family shows three major acquisitions—the Bellini Madonna (cat. 14, 44.552), the Belliniano double portrait (cat. 20, 44.553), and the Ferrarese tondo (cat. 15, 44.574)—positioned behind them (see fig. 3), and second, Creighton Gilbert recalled “seeing the beautiful Bartolommeo Veneto portrait [cat. 19, 44.573] in the place of honor above the fireplace.”15 The parlor or drawing room was the largest room in the apartment and would offer proper space for the large number of works. It is also likely that the Strauses’ parlor was the room where the family would gather. The arrangement of paintings in this room was the most varied, featuring works of the Italian, Flemish, German, and French schools, with a wide range of themes. The family photograph shows the three works of art hung individually, rather than stacked as in the salon style. Dianne Sachko Macleod has observed that this formal, museum-like arrangement is the way male collectors demonstrated pride in their artwork: “individual ‘masterpieces’ are highlighted as distinct entities apart from the decorative arts.”16 Percy’s grandson Brad Straus recalls that family members and guests, even the children, were instructed to view the works individually, not as a whole.17 Brad’s memories support the position that the Strauses were strongly attached to their collection and that its distribution throughout their apartment at 875 Park Avenue was thoughtful and personal.

Cornerstone of the European Collection at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Marjorie and Percy Selden (Percy S. Straus, Jr.) with James Chillman, director of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1953.

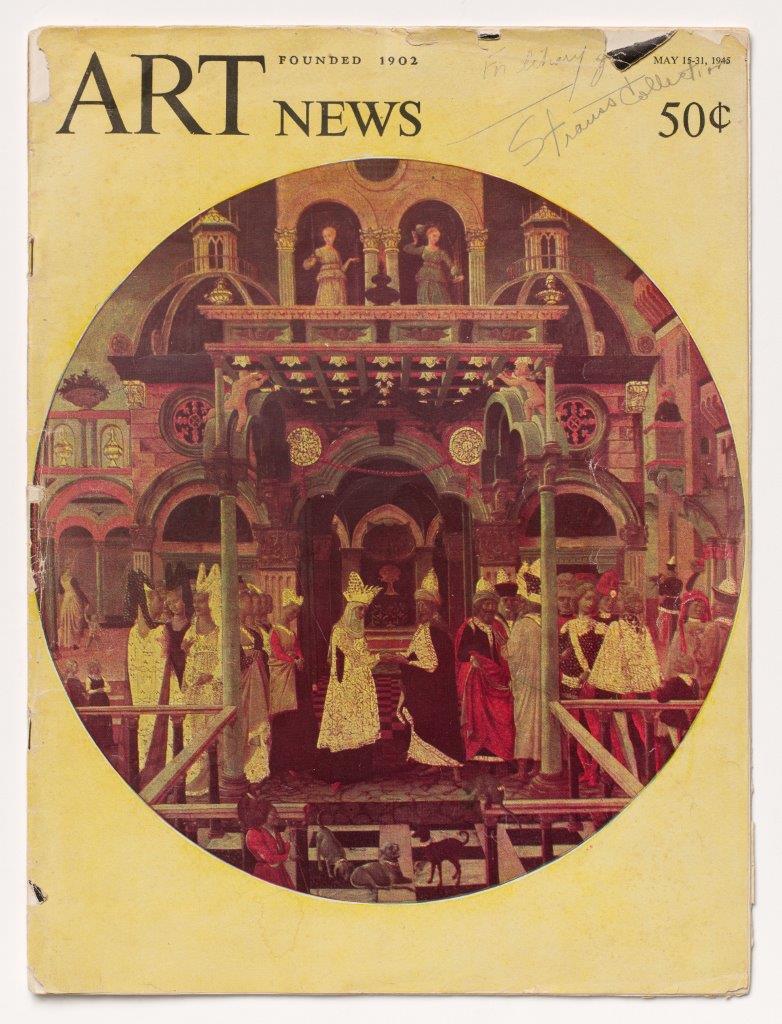

Art News cover, May 1945, featuring the Straus Collection.

The donation of the Edith A. and Percy S. Straus Collection fundamentally changed the scope and importance of the European collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Although the announcement of the intended bequest was published on December 7, 1941, when it was overshadowed by the reports of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the gift was rightfully celebrated as a turning point for the Museum. The eighty-three objects that arrived in late 1944, after Percy Straus’s passing earlier in the year, not only formed the cornerstone of the European collection, but put the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, firmly on the map. According to the terms of the gift, the objects were to be shown together for five years, after which they could be dispersed among the collection. It was not a difficult stipulation since the European department held only twelve other paintings at the time. The Straus Collection immediately went on view in early 1945. The accompanying slender catalogue speaks of the constraints of the times but contains important information, including short entries on all the works and some excellent black and white photographs. In the foreword, the reason for the donation of the New York collection to a fledgling institution halfway across the continent is only summarily addressed. The Strauses’ confidence in the rising economic and political importance in the cities of the Southwest was coupled with a wish to give the residents of those cities access to world-class art. Their belief in Houston’s future was undoubtedly kindled by Jesse Jones, the important Houston businessman and philanthropist, who was a close friend. A significant impetus was likely the fact that their son Percy Selden Straus, Jr. (later known as Percy Selden) and his Dallas-born wife, Lillian Marjorie Jester, had moved to Houston in 1939. The promised major gift elevated the young couple’s standing in the community, and they naturally took an active interest in the growing museum (fig. 4). It acted as a catalyst in attracting further remarkable donations in European paintings, such as the Samuel H. Kress Collection of Renaissance and Baroque paintings, and more recently the John A. and Audrey Jones Beck Collection of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist works.

The Straus Collection deserved and was awarded much scholarly attention since it entered the museum. Percy Straus had been a very private person who did not care for publicity or notoriety, and his collection, assembled for his private enjoyment, was therefore little known. The first to publish it was Richard Offner, Straus’s highly esteemed advisor in Italian Renaissance painting. In his article in Art News in May 1945 (fig. 5), Offner celebrated it as one of the finest private collections in America to have been given to the public. He discussed many of the most outstanding works, arguing for his attributions to various artists. In the following decades numerous scholars have studied the works, foremost among them Carolyn C. Wilson, who closely examined and published a catalogue of the Museum’s Italian paintings in 1996, and Jeremy Warren, who assessed the sculptures for the present catalogue. Furthermore, Edgar Peters Bowron and Mary Morton included many Straus works in their catalogue Masterworks of European Painting in the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, published in 2000. A focus exhibition on the Straus Collection organized in 2017 served as catalyst of this publication. It is intended as the expression of the high esteem in which this collection—so assiduously assembled a century ago by an exemplary connoisseur, collector, and philanthropist—is held by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and its visitors.

—Helga Kessler Aurisch with Maureen Chaouch

Notes

- Percy S. Straus obituary, New York Times, April 8, 1944.

- Isidor Straus, The Autobiography of Isidor Straus (Smithtown, NY: Straus Historical Society, 2011), 54–56.

- Straus, Autobiography of Isidor Straus, 54–56.

- Joan Adler, “Strauses and the Arts,” Straus Historical Society, Inc. Newsletter 15, no. 2 (February 2014), 6, 8.

- Straus Historical Society documents, Smithtown, NY.

- Straus Historical Society documents.

- Straus, Autobiography of Isidor Straus, 69.

- The section “The Collection in the Straus Home” is by Maureen Chaouch.

- Pease & Elliman, Catalogue of East Side of New York Apartment Plans (New York: Pease and Elliman, 1925), 174–75.

- This was stated by the building’s current superintendent and is corroborated by the New York City Department of Buildings 1945 certificate of occupancy.

- The Edith A. and Percy S. Straus Collection Papers, MS 15, binder 2, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, archives.

- Carolyn C. Wilson, Italian Paintings, XIV–XVI Centuries in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in association with Rice University Press and Merrell Holberton, 1996), 14.

- Gervase Jackson-Stops and James Pipkin, The English Country House: A Grand Tour (London: The National Trust, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1985), 124–26.

- Colin B. Bailey, Building the Frick Collection: An Introduction to the House and Its Collections (New York: The Frick Collection and Scala Publishers, 2006), 49.

- Wilson, Italian Paintings, 14.

- Dianne Sachko Macleod, Enchanted Lives, Enchanted Objects (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), 23.

- Interview with Brad Straus, January 27, 2018.