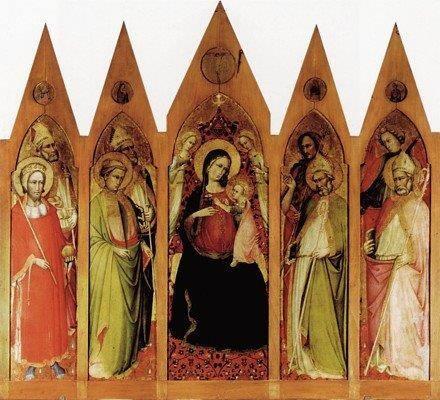

Virgin and Child

Frame: 45 13/16 × 27 1/2 in. (116.4 × 69.9 cm)

Andreatta, Emanuela. In L’età di Masaccio: Il Primo Quattrocento a Firenze, edited by Luciano Berti and Antonio Paolucci. Milan: Electa, 1990.

Bellosi, Luciano. La pittura tardogotica in Toscana. Milan: Fratelli Fabbri Editori, 1966.

Benazzi, G. In Patrizia Felicetti. Arte in Valnerina e nello Spoleto: Emergenza e tutela permanente: catalogo della mostra: Ex Chiesa S. Niclolò, 25 giugno – 30 agosto 1983. Rome: Multifrafica, 1983.

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: Florentine School: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works, with an Index of Places. London: Phaidon, 1963.

Boccia, Lionello G., Carla Corsi, Anna Maria Maetzke, and Albino Secchi. Arte nell’Arentino: Recuperi e restauri dal 1968 al 1974. Florence: Edam, 1974.

Borenius, Tancred. “A Madonna by the Compagno d’Agnolo.” Burlington Magazine 40, no. 230 (May 1922): 233, repr. 232.

Boskovits, Miklós. “Der Meister der Santa Verdiana: Beiträge zur Geschichte der florentinischen Malerei um die Wende des 14. und 15. Jahrhunderts.” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Instituts in Florenz 8, no. 1–2 (Dec. 1967): 48.

Boskovits, Miklós. Pittura fiorentina : alla vigilia del Rinascimento : 1370–1400. Florence: Edam, 1975.

Boskovits, Miklós, ed., et al. The Martello Collection: Paintings, Drawings, and Miniatures from the XVIth to the XVIIIth Centuries. Florence: Centro Di, 1985.

Brandi, Cesare. Quattrocentisti senesi. Milan: Hoepli, 1949.

Brezzi, Elena Rossetti. In Duecento e il Trecento, II. Milan: Electa, 1986.

Carnegie Institute. Catalogue of Painting Collection: Museum of Art, Carnegie Institute. Pittsburgh: Carnegie Institute, Museum of Art, 1973.

Chiodo, Sonia. “Pittori attivi in Santo Stefano al Ponte a Firenze e una proposta di identificazione per il Maestro della Madonna Straus.” Paragone 49, no. 577 (March 1998): 48–79.

Cole, Bruce. Masaccio and the Art of Early Renaissance Florence. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1980.

Eisenberg, Marvin. Lorenzo Monaco. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989.

Fabbi, D. A. “Appunti d’archivio: Artisti fiorentini nel territorio di Norica.” Rivista d’arte, 3rd ser., 9, no. 34 (1959): 117.

Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1972.

Fremantle, Richard. Florentine Gothic Painters from Giotto to Masaccio: A Guide to Painting in and near Florence 1300 to 1450. London: Martin Secker and Warburg, 1975.

Fremantle, Richard. Florentine Painting in the Uffizi. London: Martin Secker and Warburg, 1975.

Friedmann, Herbert. The Symbolic Goldfinch: Its History and Significance in European Devotional Art. Washington, D.C.: Pantheon Books for Bollingen Foundation, 1946.

Klesse, Brigitte. Seidenstoffe in der italienischen Malerei des 14. Jahrhunderts. Bern: Stämpfli, 1967.

Laclotte, Michel, and Elisabeth Mognetti. Avignon—Musée du Petit Palais : Peinture italienne. Paris: Edition des Musées Nationaux, 1976.

Longhi, Roberto. “Ricerche su Giovanni di Francesco.” Pinacotheca 1, no. 1 (July–Aug. 1928 –VI): 34. Repr. in Roberto Longhi, ‘Me Pinxit’ e questi caravaggeschi: 1928–1934. Florence: Sansoni, 1968.

McTavish, David. The Arts of Italy in Toronto Collections: 1300 – 1800. Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario, 1981–82.

Marzio, Peter. A Permanent Legacy: 150 Works from the Collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. New York: Hudson Hills, 1989.

Offner, Richard. “Il Mostra del Tesoro di Firenze Sacra – II.” Burlington Magazine 63, no. 367 (October 1933): 170, n. 14.

Offner, Richard. “The Straus Collection Goes to Texas.” Art News 44, no. 7 (May 15–31, 1945): 12, cat. 12.

Paolucci, Antonio. In ,L’età di Masaccio: Il Primo Quattrocento a Firenze, edited by Luciano Berti and Antonio Paolucci. Milan: Electa, 1990.

Procacci, Ugo. “Opere d’arte inedite alla Monstra del Tesoro di Firenze Sacra.” Rivista d’arte, 2nd ser., 15, no. 2 (April–June 1933), 230, n.2, 244, n. 1.

Salvini, Roberto. “Per la cronologia e per il catalogo di un discepolo di Agnolo Gaddi.” Bollettino d’arte, ser. 3, XXIX: 6 (Dec. 1935), 294, n. 11.

Shapley, Fern Rusk. Paintings from the Samuel H. Kress Collection, vol. I. London: Phaidon, 1966.

Shaw, James Byam. Paintings by Old Masters at Christ Church Oxford. London: Phaidon, 1967.

Schrader, Jack. In A Guide to the Collection. Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1981.

Skaug, Erling, S. Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico, vol. 2. Oslo: IIC Nordic Group, 1994.

Strehlke, Carl Brandon. Italian Paintings, 1250–1450, in the John G. Johnson Collection and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, in association with the Pennsylvania State University Press, 2004.

Tartuferi, Angelo. “Qualche considerazione sul Maestro della Madonna Straus e due tavole inedite.” Arte cristiana, n.s., 75, no. 720 (May–June 1987): 161–62.

Van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting, vol. 9. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1927.

Van Os, Henk Willem and Marian Prakken. The Florentine Paintings in Holland 1300–1500. Maarssen: Gary Schwartz, 1974.

Volpe, Carlo, ed. Early Italian Paintings and Works of Art: 1300–1480. London: Matthiesen Fine Art, 1983.

Walters Art Gallery. The International Style: The Arts in Europe around 1400. Baltimore: Walters Art Gallery, 1962.

Wildenstein (London). The Art of Painting in Florence and Siena from 1250–1500: A Loan Exhibition. London: Curwen Press, 1965.

Wilkins, David. “A Florentine Diptych.” Carnegie Magazine 47, no. 4 (April 1973):158.

Wilson, Carolyn C. Italian Paintings, XIV–XVI Centuries, in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in association with Rice University Press and Merrell Holberton, 1996.

Zeri, Federico. Italian Paintings in the Walters Art Gallery, I. Baltimore: Published by the Trustees, 1976.

Zeri, Federico, and Paul A. Underwood. “Il Maestro di Santa Verdiana.” Studies in History of Art Dedicated to William E. Suida on His Eightieth Birthday. New York: Samuel H. Kress Foundation, 1959.

ProvenanceCarlo Pini, c. 1898; acquired by James Kerr Lawson, Settignano, Italy; acquired by Edward Hutton (1875–1969), London; acquired by Percy S. Straus, New York, 1926; bequeathed to the MFAH, 1944.

This exquisite image of the Virgin and Child is indisputably the lodestar of the Straus Collection. Richard Offner, the renowned connoisseur of Florentine painting, whose opinion Percy S. Straus sought when he considered this acquisition, wrote in 1926 that he had already known the painting for fourteen years and loved it. Offner further pointed out that he had assembled about three dozen works by the hand of this anonymous master, but had not been able to ascertain his name.1 He had considered naming him “Amico di Agnolo” because of his closeness to Agnolo Gaddi, a Florentine master active between 1369 and 1396, whose father, Taddeo Gaddi (1290–1366), had been Giotto’s most renowned pupil. However, the artist was ultimately named after the Straus Collection, the repository of this, his most outstanding work.2 Carolyn C. Wilson has carefully analyzed the scholarly debate around this anonymous master, tracing it from Roberto Longhi’s initial publication, assigning the name of Master of the Straus Madonna in 1928, through the authoritative findings by Federico Zeri, Luciano Bellosi, and Miklós Boskovits and up to the contributions Angelo Tartuferi, Marvin Eisenberg, and Antonio Paolucci.3 It is generally believed that this master was active from the 1360s to the first decades of the fifteenth century. He most likely spent time in Agnolo Gaddi’s workshop early in his career and evolved into a remarkable master in his own right by the late 1300s. It is also believed that he may have been instrumental in the training of Masolino and possibly Fra Angelico,4 thus playing a role in the formation of some of the greatest representatives of early Renaissance painting in Florence. So far, his name has remained elusive. However, research is ongoing, and Sonia Chiodo, based on her findings in the archives of the church of Santo Stefano al Ponte in Florence, has proposed the name of Ambrogio di Baldese. Chiodo discovered that a polyptych, Madonna Enthroned with Saints and Angels, was commissioned by the Compagnia di Orsanmichele in 1413, for a chapel in Santo Stefano donated by the Gherardini family, from Ambrogio di Baldese (fig. 8.1). Sometime between 1556 and 1585, this altarpiece seems to have been removed to a small church in San Donato at Citili, a tiny settlement south of Florence that was part of the Gherardini family’s dominions. Now in the nearby church of Sacro Cuore at Greti, this work has been attributed by numerous scholars to the Master of the Straus Madonna.5 If Chiodo’s identification of this altarpiece as the one painted for the chapel of the Gherardini family in Santo Stefano al Ponte, for which Ambrogio di Baldese received payment in April 1417 from the Compagnia di Orsanmichele, is correct, the puzzle of the true identity of the Master of the Straus Madonna can be considered resolved. Indeed, several of the foremost scholars of this field, including Laurence B. Kanter and Carl Brandon Strehlke have accepted this finding, which is also supported by the undeniable stylistic similarities between Baldese’s Madonna del Latte at Empoli (fig. 8.2), the Greti altarpiece (see fig. 8.1) and the Madonna and Child in the Straus Collection. They include the virtually identical manner in which the Madonna has bared her left breast for the Child in the Greti and Empoli panels, as well as her very elongated, tapered fingers. The Straus Madonna shares the same delicate facial features with the Madonna of the Empoli. In both cases, the Child is portrayed as much more robust than the Mother, a well-nourished infant actively grasping a goldfinch in his left.

The Straus panel is distinguished above all by its elegance of line, a hallmark of trecento Florentine painting. The emphasis on line is obvious both in the contour of the figural group as well as in the figures’ individual parts. The idealized features of the Madonna and the Child are carefully drawn, and the hands and fingers are clearly articulated. Within the outlines, however, there is a noticeable attempt at subtle modeling through shading, giving the figures more corporality. Highlights appear on the Virgin’s forehead, brow, cheek, and chin as well as on the face of the Child and on his left shoulder and chest. Their pale complexions are enlivened by pink cheeks and red lips, which probably caused Offner to call these figures “all milk and roses.”6 The Madonna is clad in a dark blue mantle—its inside flecked with gold—that is ornamented with an embroidered golden border and a band of stars falling from the top of her head onto her shoulder. Her long-sleeved golden-yellow dress worn under the mantle is gathered into soft pleats by a thin belt just below the bosom. It has an ornamental border at the neckline and a delicate allover motif of stars. Thus, even without a crown, she is clearly defined as the queen of heaven. Though the symbolic colors of red and blue for the Virgin had not been canonized at the time of this painting, the combination of a blue mantle with a golden-yellow dress can be found in many instances by various late trecento Florentine artists. Here, it is balanced by the gold and red cloth wrapped around the Christ Child’s lower body. The tunic-like garment worn by the child has a long tradition in Florentine painting and can already be found in Giotto’s works.7 The present example is distinguished by its particularly fine treatment of the diaphanous material, embellished with bands of gold embroidery at the top of the sleeves and around the neckline. Hanging from a black string around the child’s neck is a piece of coral. Traditionally believed to ward off disease, coral was often worn as a charm by young children and is frequently found in children’s portraits.8 In this instance, its cruciform shape can be seen to presage Christ’s suffering on the cross.

Like the coral, the little goldfinch held by the child can be read as a symbol of Christ’s Passion, but it was often also worn as a protector against disease, especially the plague. Herbert Friedmann, in his comprehensive study, points out that the earliest example of a goldfinch dates to the 1270s in Florentine painting.9 Unsurprisingly, it rose to great popularity in Florence, where half the population perished during the outbreak of the “Black Death” of 1346–50, a death toll twice as high as that of most European cities. Thus, the goldfinch is found in the works of Bernardo Daddi and Allegretto Nuzi, dating around 1350,10 and remained popular until the later 1300s. It features in Agnolo Gaddi’s Parma altarpiece of 1375 (fig. 8.3), as well as in several works attributed to the Master of the Straus Madonna, such as the small diptych of the Madonna and Child and Crucifixion in the Carnegie Museum and the Madonna and Child in the Bonnenfanten Museum, Maastricht (fig. 8.4).11

The twofold gesture of the Madonna’s exaggeratedly long index finger pointing toward the Child and his grasping it forms the compositional and symbolic center of the present work. This has been closely analyzed by Dorothy C. Shorr, who interpreted the Madonna’s gesture as referring to her role as Hodegetria, the Madonna type who points to the Incarnate God, while Miklós Boskovits saw in the Child’s gesture an “allusion to Christ’s foreordained sacrifice.”12 Giotto already incorporated a similar gesture in his San Giuseppe Madonna of 1310–15 (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.), as did Bernardo Daddi in his Madonna and Child thirty years later (Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza).13 According to Wilson, another possible source is a fresco by an unknown Sienese painter in a lunette in the main cloister of the church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence that dates to the 1330s.14 From 1344 on, this fresco was considered a miracle-working image and, as such, may well have served as the direct inspiration for the Master of the Straus Madonna. It is similar in the placement of the gestures that symbolizes Christ’s sacrifice, the central tenant of Christian faith, as the compositional and ideological focus of the painting.

The Master of the Straus Madonna has, moreover, made effective use of the decorative elements in this work to enrich his composition with further symbols. Thus, the Madonna’s golden halo is ornamented with a continuous vine in punchwork, and that of the Christ Child bears a cross motif, interspersed with segments showing stylized floral shapes. The beautiful hanging behind the Madonna, a textile most likely imported from the Middle East, is patterned with exotic griffins set in a repeat pattern of vines. While the floral and cross motifs are easily understood within Christian iconography, the griffins are more difficult to interpret. This mythological hybrid animal of Eastern origin, consisting of the head of an eagle and the body of a lion, has been used since antiquity as the guardian of great treasure and can be seen here to guard the most precious child, the Son of God, and his mother. The cloth of honor and the other textiles are rendered in an array of brilliant colors that add substantially to the overall effect of the jewel-like splendor of this panel.

As noted above, Offner saw a great similarity between this panel and the works of Agnolo Gaddi. He admired the almost overripe sweetness of the figures that constituted part of the “cult of feminine refinement,” which he considered a characteristic of Gaddi’s style.15 Indeed, the Master of the Straus Madonna’s proximity to Gaddi can readily be followed by comparing this panel with a number of the older master’s paintings. The same facial features—especially the elongated oval face, long nose, small almond-shaped eyes, and pointed chin of the Madonna and the round face and tightly curled blond hair of the Child are found on Gaddi’s central panel of the triptych in Parma (see fig. 8.3), the central panel with the Madonna and Child with Saints and Angels (1380), in the Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, the triptych in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (Madonna and Child with Saints and Angels, shortly before 1387), and a another triptych of the same subject, dated 1388, in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin. Although many details such as the luxurious textiles, the goldfinch, and the coral amulet appear repeatedly, the triptych in Parma, the earliest of these works, corresponds most closely with the present panel. The similarities extend to the diaphanous tunic worn by the Child and the Virgin’s golden garment. Although there are no direct quotations, the stylistic affinity gives credence to the close association between the Master of the Straus Madonna and Agnolo Gaddi during the former’s early career.16

A proximity between the Master of the Straus Madonna and other artists has been discussed by scholars in the field as well. A closeness to Gherardo Starnina (1354–1413) and Lorenzo Monaco (1379–1425) are both mentioned by Wilson.17 Unfortunately, the small number of Starnina’s documented extant works makes comparisons between the two very difficult. On the other hand, the parallel developments of Lorenzo Monaco and the Master of the Straus Madonna are notable. In particular, Lorenzo’s Maestà in the Fitzwilliam Museum lends itself to a comparison with the present work. Despite obvious differences, the similarities extend to the type of curly-haired Child wearing a diaphanous tunic with a voluminous cloth wrapped around his hips and holding a goldfinch.

Within the oeuvre attributed to the Master of the Straus Madonna, the closest works are a diptych today in the Carnegie Museum of Art, a Madonna and Child in the Bonnenfanten Museum, Maastricht (fig. 8.4), and the Madonna and Child with Saints Matthew and Michael in San Giuseppe, Florence. Based on the attribution of these works to the Master of the Straus Madonna, numerous scholars have proposed him as a possible teacher of Masolino (1383–1447), who together with Masaccio (1401–1428) painted the Brancacci Chapel in Santa Maria del Carmine, one of the greatest monuments of early Florentine Renaissance painting. The role the Master of the Straus Madonna played as the teacher of the very young Fra Angelico has gained considerable weight since Chiodo’s findings of a payment to him for work done on the Greti altarpiece (see fig. 8.1). Strehlke believes that Fra Angelico scraped down Baldese’s predella and painted two scenes from the legend of Saint Michael (Yale University Art Gallery), for which he was paid twelve florins in 1418. Thus, two widely dispersed parts of this altarpiece, one at Greti, the other in New Haven, Connecticut, may well be the keys to the identification of the Master of the Straus Madonna as Ambrogio di Baldese and of his tutelage of Fra Angelico.

One of the distinctions of the Straus panel is its beautiful, largely original engaged frame, consisting of a predella, colonnettes, and an arched top with flaming acanthus leaves. However, during a conservation treatment in 2000, earlier losses that had been covered by historically incorrect additions were replaced. While the predella and the sides of the frame are original, the former arched top, which was too narrow and covered some of the cloth of gold, was removed and replaced with a wider arch that allows the entire painted surface to be visible. Furthermore, the architraves were lowered to their original position and the missing set of colonnettes added. These thoughtfully executed changes enhance the overall impact of this masterwork of devotional painting that very likely held pride of place in a Florentine home on the cusp of the Renaissance, and is today one of the treasures of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

—Helga Kessler AurischNotes

1. Richard Offner to Percy S. Straus, 5 October 1926, the Edith A. and Percy S. Straus Collection, MS 15, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, archives.

2. Offner to Straus, 5 October 1926. Wilson points out that Borenius had been the first to publish the work and traces the history of its attribution from 1927 onward; see Carolyn C. Wilson, Italian Paintings, XIV–XVI Centuries, in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in association with Rice University Press and Merrell Holberton, 1996), 106–9.

3. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 101–3.

4. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 101, and Sonia Chiodo, “Pittori attivi in Santo Stefano al Ponte a Firenze e una proposta di identificazione per il Maestro della Madonna Straus,” Paragone 49, no. 18 (577) (March 1998): 57.

5. Chiodo, “Pittore attivi.”

6. Richard Offner. “Il Mostra del Tesoro di Firenze Sacra–II.” Burlington Magazine 63, no. 367 (October 1933): 170.

7. Richard Fremantle, Florentine Painting in the Uffizi (London: Martin Secker & Warburg, 1975), ills. 1, 7.

8. Herbert Friedmann, The Symbolic Goldfinch (Washington, D.C.: The Bollingen Foundation, 1946), 10.

9. Friedmann, Symbolic Goldfinch, 65.

10. Carl Brandon Strehlke, Italian Paintings, 1250–1450, in the John G. Johnson Collection and the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, in association with the Pennsylvania State University Press, 2004), 25, pl. 1C, and 35, pl. 4. Both images, dated 1346 and 1366, illustrate the same gesture very closely, albeit in reverse.

11. Friedmann, Symbolic Goldfinch, 67, mentions Giotto’s pupils Taddeo Gaddi, Bernardo Daddi, and Jacopo del Casentino as most prolific users of goldfinch symbolism.

12. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 112.

13. Fremantle, Florentine Painting, 270, ill. 548.

14. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 112, fig. 8.10.

15. Offner, Il Mostra, 170.

16. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 101.

17. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 101.

Comparative Images

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has made every effort to contact all copyright holders for images and objects reproduced in this online catalogue. If proper acknowledgment has not been made, please contact the Museum.