This large and somewhat puzzling painting has become one of the favorites for visitors to the European collection, who are enticed by its curious three-part narrative and its charming details. Its authorship by the Sienese Bernardino Fungai (Bernardino Cristofano di Nicholo d’Antonio di Pietro da Fungaia) was established early in the twentieth century and has never been doubted.1 In his monograph on the artist, Peleo Bacci published a document that verifies Fungai as the pupil of Benvenuto di Giovanni in 1482,2 but scholars have not been able to identify any works before the 1490s.3 A chronology of his works has furthermore been difficult to assemble because of the huge gap between verifiable dates. He is documented to have been commissioned in 1494 to paint works of lesser importance such as ceremonial banners,4 but his only dated and signed painting, Madonna and Child Enthroned, with Saints Sebastian, Jerome, Nicholas of Bari, and Anthony of Padua (Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena), was completed in 1512, just four years before his death.5

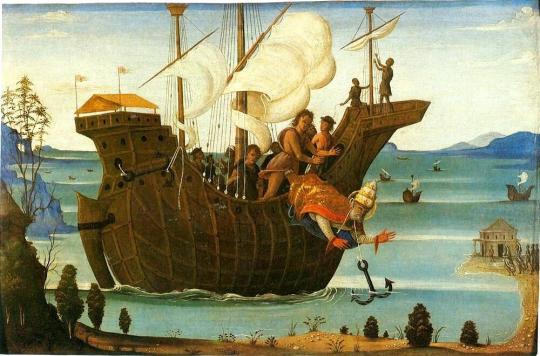

If we accept the date of around 1510 for the Straus panel, as proposed by Richard Offner, or 1512 suggested by Carolyn C. Wilson, a small painting today in the City Art Gallery, York, that has been identified as part of the predella of Fungai’s Coronation of the Virgin altarpiece (1498– 1501; Santa Maria dei Servi, Siena) may be considered its precursor (fig. 18.1).6 It depicts the martyrdom of Saint Clement, who, in full papal regalia with an anchor tied around his neck, is being pushed off a large ship. Not only the action but also many details are echoed in the Straus painting. In particular, the ships, whose construction and rigging are carefully detailed, are virtually identical. Their magnificent sails, delicately ornamented in gold, billow dramatically above the crowd of men onboard. Despite the wind-filled sails, they seem to lie almost motionless in close proximity to the shore, dwarfing the nearby buildings. While Fungai is focused on a single episode of the saint’s life in the predella, he tells a much more expansive story on the Straus panel.

Here, a somewhat obscure mythical subject is depicted that was originally misidentified by F. Mason Perkins as the story of Hippo.7 However, after a thorough investigation, Wilson was able to successfully identify it as the story of the Beloved of Enalus who was sacrificed to Poseidon but saved, based on a text by Plutarch and Anthenaeus.8 Read from right to left, the panel illustrates the story of the beautiful young woman who is pushed or jumps into the sea from an impressive ship under full sail that is crowded with soldiers. Her sacrifice, however, is averted. Instead of drowning, she is rescued by a youthful Poseidon, standing on a richly ornamented base that rises from the water. With the aid of two of his dolphins, the young woman swims to shore and is pulled out of the water by elegantly clad women who have been identified variously as settlers of the Isle of Lesbos, Amazons, or Diana’s nymphs.9 Their identity, however, remains puzzling: they are not armed warrior maidens, nor do they seem to be nymphs, who are generally depicted in the nude. The identity of the island as Lesbos—a place inhabited solely by women according to Greek mythology—is put into question by the presence of several men who are seen walking, riding, and fishing in the distance. Thanks to Fungai’s lyrical painterly style and his mastery in depicting minutely rendered details in the context of a larger narrative, these small discrepancies do not disrupt the visual enjoyment of the overall work. The panoramic landscape is imbued with a sense of tranquility that serves as a counterpoint to the turbulent actions of the protagonists. Curiously, the landscape is also peopled with figures on a much smaller scale than the main figures, who are seemingly unaware of the main story. The various gilded details, such as the sun’s rays that reach far across the sky, the outline of the acorns and fruits on the trees, and the brocaded costumes of the elegantly clad figures simply delight the eye. Perkins, who first saw the stylistic similarities with Pinturicchio, considered this panel one of Fungai’s most beautiful works, pointing out its “poetic concept, the perfect technique, the freshness of the landscape, the grace of the various figures, and the refinement of details.”10 The panel was previously thought to have been part of a cassone (marriage chest), but its size points to its use as a wall decoration, a spalliera, perhaps installed in the bedchamber of a newly married couple.11

The Straus panel, together with a series of panels illustrating the life of the Roman general Scipio Africanus (the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow, and the State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg [fig. 18.2]), are today considered Fungai’s most remarkable works.12 Probably painted somewhat earlier, the Scipio panels are stylistically less refined than the Straus panel.13 On these panels the narrative moves toward the center from both sides, not from right to left as in the story of the Beloved of Enalus. The focal group in each case surrounds the slight figure of Scipio Africanus, enthroned on a magnificent golden throne with cornucopia armrests and claw feet. He is clearly identified by name in gold letters, as are some of the other protagonists. While this allows the viewer some certainty in regard to the subject matter, the lack of any kind of identification adds an element of mystery to the Straus panel, leaving some room for interpretation. There are great similarities in the landscape, but that of the Straus panel is more expansive and tranquil and the movement of the figural groups is also more deftly handled. It is undoubtedly a masterpiece and worthy of its distinguished provenance. Until a few years before its acquisition by Percy S. Straus, it had been part of the distinguished collection of Baron Maurice de Rothschild in Paris.

—Helga Kessler Aurisch

Notes

1. Keith Christiansen, Laurence B. Kanter, and Carl Brandon Strehlke, Painting in Renaissance Siena, 1420–1500 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988), 352; Carolyn C. Wilson, Italian Paintings, XIV–XVI Centuries, in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in association with Rice University Press and Merrell Holberton, 1996), 260.

2. Pèleo Bacci, Bernardino Fungai: Pittore Senese (1460–1516) (Siena: Stabilimento Arte Graffiche Lazzeri, 1947), 12.

3. Christiansen, Kanter, and Strehlke, Painting in Renaissance Siena, 352.

4. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 256.

5. Christiansen, Kanter, and Strehlke, Painting in Renaissance Siena.

6. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 261.

7. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 260.

8. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 261.

9. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 262.

10. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 260.

11. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 260.

12. Christiansen, Kanter, and Strehlke, Painting in Renaissance Siena, 352.

13. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 263.

The Beloved of Enalus Sacrificed to Poseidon and Spared

Frame: 32 1/2 × 92 3/4 in. (82.6 × 235.6 cm)

Bacci, Pèleo. Bernardino Fungai: Pittore Senese (1460–1516). Siena: Stabilimento Arte Graffiche Lazzeri, 1947.

Berenson, Bernard. “Lost Works of the Last Sienese Masters,” part 3. International Studio (April 1931): 21.

Berenson, Bernard. The Italian painters of the Renaissance. London: Oxford University Press, 1932.

Berenson, Bernard, and Emilio Cecchi. Pitture italiane del Rinascimento: catalogo dei principali artisti e delle loro opere con un indice dei luoghi. Milan: U. Hoepli, 1936.

Berenson, Bernard. The Italian Painters of the Renaissance, vols. 1, 2. London: Phaidon, 1968.

Berenson, Bernard. Homeless Paintings of the Renaissance. London: Thames & Hudson. 1969.

Carli, Enzo. "Dipinti Senesi Nel Museo Houston." Antichità viva 4 (April 1963): 24–25, figs. 11–14.

Charboneau, Damian M. “The Fungai Altarpiece in Santa Maria dei Servi in Siena (1498–1501): Rare Exhibit Reunites Lost Predella Pieces.” Studi storici dell’Ordine dei Servi di Maria 39, nos. 1–2 (1989): 163.

Christiansen, Keith, Laurence B. Kanter, and Carl Brandon Strehlke. Painting in Renaissance Siena, 1420–1500. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988.

Cole. Bruce. Sienese Painting in the Age of the Renaissance. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985.

Dizinario enciclopedico Bolaffi dei pittori e degli inscisori italiani: dall’XI al XX secolo, V. Turin: G. Bolaffi; G. Mondadori, 1974.

Faenson, Liubov. Italian Cassoni from the Art Collections of Soviet Museums. Leningrad: Aurora, 1983.

Fredericksen, Burton B. and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1972.

Hind, Arthur M. Early Italian Engraving, I: 1. London: Quaritch, 1938.

Kanter, Laurence B. In Painting in Renaissance Siena: 1420‒1500. Edited by Keith Christiansen, Laurence B. Kanter, and Carl Brandon Strehlke. Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988.

Marandel, J. Patrice. In The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston: A Guide to the Collection. Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1981.

Misciatelli, Piero. “Cassoni senesi.” La Diana, 4, no. 2 (1929): 125, pl. 34.

Offner, Richard. “The Straus Collection Goes to Texas.” Art News 44, no. 7 (May 15–31, 1945): 16–23.

Perkins, F. Mason, “Alcuni dipinti senesi sconosciuti o inediti.” Rassenga d’arte 13, no. 8 (August 1913): 125–26.

Perkins, F. Mason. “Two Panel Pictures by Bernardino Fungai.” Apollo 15 (April 1932): 145.

Pope Pius, Maria Lusia Doglio, ed. Enea Silvio Piccolomini: Storia di due amanti e rimedia d’amore. Turin: Unione Tipografico-Editrice Torinese, 1972.

Scharf, Alfred. A Catalogue of Pictures and Drawings from the Collection of Sir Thomas Merton, F.R. S. at Stubbings House, Maidenhead. London: Chiswick, 1950.

Schubring, Paul. Cassoni: Truhen und Truhenbilder der italienischen Frührenaissance. Leipzig: Karl W. Hiersemann, 1915; 1923 ed.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Catalogue of the Edith A. and Percy S. Straus Collection. Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1945.

Van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting, XVI. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1937.

Wilson, Carolyn C. “Bernardino Fungai and a Theme of Human Sacrifice.” Antichità viva 34, nos. 1/2 (1995): 29–42, figs. 1, 3, 7, 16–20.

Wilson, Carolyn C. Italian Paintings, XIV–XVI Centuries, in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in association with Rice University Press and Merrell Holberton, 1996.

ProvenanceCollection Baron Maurice de Rothschild, Paris, by 1913; Edward A. Faust, Saint Louis, in 1929; [Wildenstein, New York]; sold to Percy S. Straus, February 7, 1938; bequeathed to MFAH in 1944.Comparative Images

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has made every effort to contact all copyright holders for images and objects reproduced in this online catalogue. If proper acknowledgment has not been made, please contact the Museum.