When Guido di Pietro entered the Convent of San Domenico in Fiesole near Florence at some point between 1417 and 1421,1 he took on the name Fra Giovanni (Brother John). But thanks to the riveting beauty and intense spirituality of his paintings, he has become known as Fra Angelico (Angelic Brother) and even the Beato Angelico (Blessed Angelic One).2

He had probably already trained as a painter and miniaturist in Florence before entering the convent, and continued to paint after taking holy orders, producing works primarily for Dominican establishments. His most celebrated achievements are the altarpiece for the high altar in the church of San Marco in Florence and the frescoes in the adjoining convent, conceived to inspire his fellow monks in their daily devotions.3 As exemplified by these masterworks, Fra Angelico was an artist at the forefront of early Renaissance painting, exploring innovations of linear perspective, the plasticity of figures and their situation in space, as well as the important role of light. He was highly acclaimed during his lifetime, and his last commission, unfortunately no longer extant, was to paint monumental frescoes in the Vatican for Pope Eugenius VI.4This exquisite small panel of Saint Anthony Abbott was first recognized as a work by Fra Angelico by Frida Schottmüller in 1925,5 and Percy S. Straus was apparently persuaded of its outstanding quality when he acquired it just five years later. The scene from the life of the hermit saint is based on the biography written by Saint Athanasius (c. 296–373), the patriarch of Alexandria, who relates that Saint Anthony Abbot was tempted by the devil with a large mass of gold. He writes that Anthony “marveled at the amount, but as one stepping over fire he passed it without turning.”6 In this depiction, however, the saint turns and recoils from the rock-size gold nugget with such force that his cloak flutters. He rushes toward the safety of the church on the hill, to which he points with his raised right hand, his stony path leading him metaphorically from evil and temptation to salvation. The incident takes place in a lonely landscape of ominous crags, some in deep shadow, some dramatically lit. Indeed, the innovative handling of light in landscape painting is acknowledged as one of Fra Angelico’s achievements. In the middle ground, a row of trees, whose differentiated foliage is carefully highlighted, leads the eye to the hills in the far distance where a crenellated wall of a fortified hilltop town or large castle is seen. A tiny church rises from the hills at the center of the composition. Despite the overall small size of the panel, the landscape has both great depth and breadth. Nonetheless, it is the figure of the saint that draws the attention above all else. His features are masterfully painted, individualized and expressive, and his energized stance enlivens the entire composition. The large golden halo, with its delicate punched pattern, acts as a counterpoint to the mass of gold, both compositionally and symbolically.

Much scholarly debate has taken place regarding the attribution of the panel to Fra Angelico since Schottmüller’s authentication in 1925. Carolyn Wilson has systematically laid this out, concluding that, despite differing opinions, the authentication is still valid, although she does not entirely preclude studio assistance.7 Giorgio Bonsanti not only includes it in his 1998 Catalogue Raisonné as autograph but deems it “of the highest quality.”8 In 2005 Laurence Kanter questioned this finding, proposing that it is a work by Fra Angelico’s close assistant Zanobi Strozzi.9 However, his conclusion, based on the comparison of the Straus St. Anthony Abbot with a panel in the Louvre, whose own attribution vacillates between Fra Angelico and Zanobi Strozzi,10 has not found wide acceptance.

Within the oeuvre of Fra Angelico, the Straus panel is seen as being close to his Strozzi Deposition (fig. 10.1), also known as the Santa Trinita altarpiece, dated around 1432. Although neither this date nor the actual commission are firmly documented, it is believed that Fra Angelico was requested by Palla Strozzi (1372–1462) to finish or alter an earlier work by Lorenzo Monacho that had been commissioned for the sacristy of Santa Trinita, a space also used as the funerary chapel of the Strozzi family.11 It is in the landscape immediately behind a group men, contemplating the instruments of Christ’s suffering—actually recognizable Florentine worthies portrayed by Fra Angelico—that we find elements very similar to those dominating the Straus panel. Here too we find the craggy cliffs, bare hills, one of them crowned with a small white church identical to the one at the center of the Straus panel, a town with crenelated walls, and the stand of trees with highlighted foliage are all suffused in sunlight that grows lighter in the distance.12 The physiological similarities of Saint Anthony Abbott with the figure of Saint John the Evangelist of the Cortona altarpiece (fig. 10.2), a work recent scholarship dates around 1434 and therefore in close proximity to the Deposition have also been noted. 13 Furthermore, a small panel in the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Cherbourg, The Vocation of Saint Augustine, is regarded by some art historians as sharing many stylistic qualities with the Straus Saint Anthony, although here too scholarly opinions differ as to the authorship.14

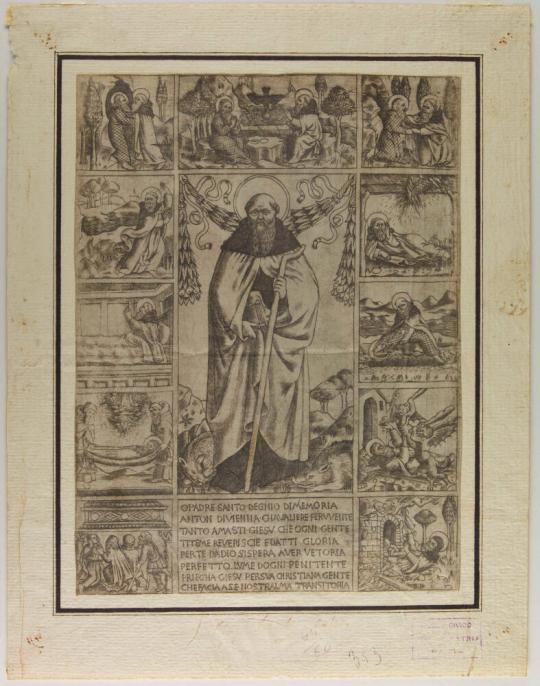

There is no disagreement regarding the function of the Straus panel as a predella, however, even though it has so far not been determined for which altarpiece it had been had intended.15 An association of the Straus panel with a large panel of the standing Saint Anthony today in the Burke Collection was first proposed by Boskowitz, who, however, knew of the image only through a photograph. Despite some stylistic differences, he believed that the two panels had been components of the same altarpiece.16 Wilson was able to substantiate this proposition with the discovery of an engraving of Saint Anthony Abbott with Eleven Scenes from his Life, today in the Museo Civico, Pavia (fig. 10.3), which includes the Straus panel on the upper left of the central image of the standing Saint Anthony. (Both images are reversed on the print.) She concedes that the relationship between the two works is still speculative, and Kanter has subsequently argued against it.17 Indeed, the measurements of the two extant panels preclude an arrangement as indicated by the print.18 Thus, despite the tantalizing documentation, the question of their original relationship remains open at present.

—Helga Kessler Aurisch

Notes

1. Christopher Lloyd, Fra Angelico (London: Phaidon, 1992), 7.

2. Edgar Peters Bowron and Mary G. Morton, Masterworks of European Painting in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press in association with the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2000), 7.

3. Bowron and Morton, Masterworks of European Painting, 8.

4. Carolyn C. Wilson, Italian Paintings, XIV–XVI Centuries, in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in association with Rice University Press and Merrell Holberton, 1996), 128–29.

5. Frida Schottmüller identified the work as by Fra Angelico in 1925, and it was acknowledged as such by a number of eminent Renaissance scholars, including Bernard Berenson, Lionello Venturi, and John Pope-Hennessy, although others such as Richard Offner were less certain; see Wilson, Italian Paintings, 138. However, Pope-Hennessy reversed his earlier judgment; see John Pope-Hennessy, Fra Angelico (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1974), 227. Boskovits retains the work as autograph; see Miklós Boskovits, “Appunti sull’Angelico,” Paragone 27 (March 1976), 43, n27; as does John Spike, Fra Angelico (New York: Abbeville, 1996), cat. 113E, 254–55. Kanter gives the work to Zanobi Stozzi, an attribution that has not been widely followed; see Laurence Kanter and Pia Palladino, Fra Angelico (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2005), 104.

6. Bowron and Morton, Masterworks of European Painting, 8.

7. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 137.

8. Giorgio Bonsanti, Beato Angelico: catalogo completo (Florence: Octavo, 1998), 132–33, cat. 43.

9. Kanter and Palladino, Fra Angelico, 104, cat. 19, fig. 62.

10. Kanter and Palladino, Fra Angelico, 104.

11. Spike, Fra Angelico, 108.

12. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 139; Spike, Fra Angelico, 106, no. 74.

13. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 139; Timothy Verdon, Beato Angelico (Milan: 24 ORE Cultura, 2015), 149.

14. Kanter and Palladino, Fra Angelico, 105 n3.

15. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 137.

16. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 139.

17. Kanter and Palladino, Fra Angelico, 104.

18. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 139; Kanter and Palladino, Fra Angelico, 104.

Saint Anthony Abbot Shunning the Mass of Gold

Frame: 12 3/16 × 13 13/16 × 3 1/8in. (31 × 35.1 × 7.9cm)

Alce, Venturino. Beato

Angelico: Miscellanea di studi. Rome: Pontificia Commissione Centrale per l’arte sacra in Italia, 1984.

Art

News

28, no. 36 (June 7, 1930), repr. 3.

Baldini, Umberto. In Mostra delle opera del Beato Angelico nel

Quinto centenario della morte (1455–1955). Florence: Museo di San Marco,

1955.

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures

of the Renaissance: a List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an

Index of Places. Oxford:

Clarendon, 1932.

Berenson,

Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance:

A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places, vol.

1. London: Phaidon, 1963.

Berenson, Bernard, and Emilio

Cecchi. Pitture italiane del

Rinascimento: catalogo dei principali artisti e delle loro opere con un indice

dei luoghi. Milan: U. Hoepli, 1936.

Berti, Luciano. “Mostra del Beato

Angelio.” Bollettino d’arte 40, no. 3

(July–September 1955): 282.

Berti, Luciano. “Miniature

dell’Angelico (e altro) – II,” Acropoli 3,

no. 1 (1963): 38n108.

Bonsanti, Giorgio. Beato Angelico:

catalogo completo.

Florence: Octavo, 1998.

Boissard, Elisabeth de. In Chantilly, Musée Condé :

Peintures de l’école italienne, by Elisabeth de Boissard and Valérie LaVergne-Durey.

Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 1988.

Boskovits, Miklós. “Appunit

sull’Angelico.” Paragone 27, no. 313

(March 1976): 43, 52n27.

Bowron, Edgar Peters, and Mary G.

Morton. Masterworks of European Painting

in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University

Press in association with the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2000.

Christiansen, Keith. “Workshop of

Fra Angelico (Guido di Pietro).” in Notable

Acquisitions 1983–1984: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: Metropolitan

Museum of Art, 1984.

Christiansen, Keith. In Painting in Renaissance Siena: 1420 – 1500, by

Keith Christiansen, Laurence B. Kanter, and Carl Brandon Strehlke. New York:

Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988.

Cole, Diane Elyse. “Fra Angelico:

His Role in Quattrocento Painting and Problems of Chronology.” PhD diss.,

University of Virginia, 1977.

Cuttler, Charles David. “The

Temptations of Saint Anthony in Art from Earliest Times to the First Quarter of

the XVI Century.” PhD diss., New York University, 1952.

Didi-Huberman, Georges. Fra Angelico, Dissemblance and Figuration. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press, 1990.

"Fra Giovanni da Fiesole,” Bulletin of the Bachstitz Gallery, n.s.,

1 (1929):16–17.

Fredericksen, Burton B., and

Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian

Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press, 1972.

Gendel, Milton. “Summer Events:

Rome.” Art News 54, no. 4 (summer

1955): 52.

Hudig, Ferrand Whaley. “Art in

Holland.” Parnassus 1 (November

1929): 19, repr. 16.

Kaftal,Georg. Iconography of the Saints in Tuscan Painting. Florence: Sansoni,

1952.

Kanter, Laurence, and Pia

Palladino. Fra Angelico. New Haven

and London: Yale University Press, 2005.

Lloyd, Christopher. Fra Angelico. London: Phaidon, 1992.

Marandel, J. Patrice. In The

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston: a Guide to the Collection. Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston,

1981.

Marandel,

J. Patrice. In Quest for Excellence:

Civic Pride, Patronage, Connoisseurship. Miami: Center for the Fine Arts,

1894.

Marzio, Peter C. A

Permanent Legacy: 150 Works from the Collection of The Museum of Fine Arts,

Houston. New York: Hudson

Hills Press, 1989.

Morante, Elsa, and Umberto Baldini,

L’opera completa dell’Angelico. Milan: Rizzoli, 1970.

Mostra delle opera di Fra Angelico nel V centenario della

morte (1455–1955). Vatican City: Palazzo Apostolico Vaticano,

1955.

Offner, Richard. “The Straus

Collection Goes to Texas.” Art News 44, no. 7 (May 15–31, 1945):

16–23.

Pope-Hennessy, John. Fra Angelico. London: Phaidon, 1952.

Pope-Hennessy, John. Fra Angelico. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1974.

Pope-Hennessy, John. Fra Angelico. Florence: Scala/Riverside,

1981.

Pope-Hennesy, John, and Laurence B.

Kanter. The Robert Lehman Collection,

vol. 1: Italian Paintings. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art; Princeton, NJ: Princeton

University Press, 1987.

Roberts, Perri Lee, Bruce Cole, and

Hayden B. J. Maginnis. Sacred Treasures:

Early Italian Panel Paintings from Southern Collections. Athens, GA: Georgia

Museum of Art, the University of Georgia, 2003.

Salmi, Mario. Il Beato Angelico. Spoleto: Arti

grafiche Panetto e Petrelli, 1958.

Schottmüller, Frida. Fra Angelico da

Fiesole. Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1924.

Shapley, Fern Rusk. Paintings from the

Samuel H. Kress Collection: Italian Schools, 13th–15th Century. London: Phaidon

for the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, 1966.

Spike, John. Fra Angelico. New York:

Abbeville, 1996.

“St. Anthony’s Flight to the

Convent by Fra Angelico da Fiesole.” Letters of Georg Gronau and Frieda

Schottmüller. Bulletin of the Bachstitz

Gallery 9/10 (1925): 98,

repr. 97.

Stanton, Dorothy. In Catalogue of a Century of Progress

Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture edited by Daniel Catton Rich. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1933.

Strehlke, Carl Brandon. “Fra

Angelico and Early Florentine Renaissance Painting in the John G. Johnson

Collection at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.” Philadelphia Museum of Art

Bulletin (Spring 1993): 20.

Strehlke, Carl Brandon. Fra Angelico

and the Rise of the Florentine Renaissance. Madrid: Museo Nacional del

Prado, 2019.

“The Connoisseur’s Diary: Fra

Angelico,” Connoisseur 136, no. 547

(August 1955): 49.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Catalogue

of the Edith A. and Percy S. Straus Collection Houston: The Museum of Fine

Arts, Houston, 1945.

Tavrisano, P. Innocenzo. Beato Angelico: L’ambiente storico; rinascita

domenicana. Rome: Fratelli

Palombi,

1955.

Urbani, Giovanni. “Angelico.” Encyclopedia of World Art, vol. 1. New

York: McGraw-Hill, 1959, col. 442.

Valentiner, Wilhelm Reinhold, and George Henry McCall. Catalogue of European Paintings and

Sculpture from 1300–1800 Masterpieces of Art; New York World's Fair, May to October, 1939. New York: Bradford,

1939.

Valentiner, Wilhelm Reinhold, and Alfred M. Frankfurter. “Guide and

Picture Book: Official Souvenir, New York World’s Fair.” The Art

News (1939): unpag. cat. no. 4.

Vaughan, Malcolm. “Old Masters at

the Fair.” Parnassus 11, no. 5 (May

1939):10.

Venturi, Lionello. Italian Paintings in America, vol. 2. New York: E.Weyhe and Milan: U. Hoepli, 1933.

Verdon, Timothy. Beato Angelico. Milan: 24 ORE Cultura, 2015.

Wilson, Carolyn C. “Fra Angelico:

New Light on a Lost Work.” Burlington

Magazine 137, no. 1112 (November 1995): 737-40, fig. 25.

Wilson, Carolyn C. Italian Paintings, XIV–XVI Centuries, in the

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Houston:

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in association with Rice University Press and

Merrell Holberton, 1996.

Comparative Images

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has made every effort to contact all copyright holders for images and objects reproduced in this online catalogue. If proper acknowledgment has not been made, please contact the Museum.