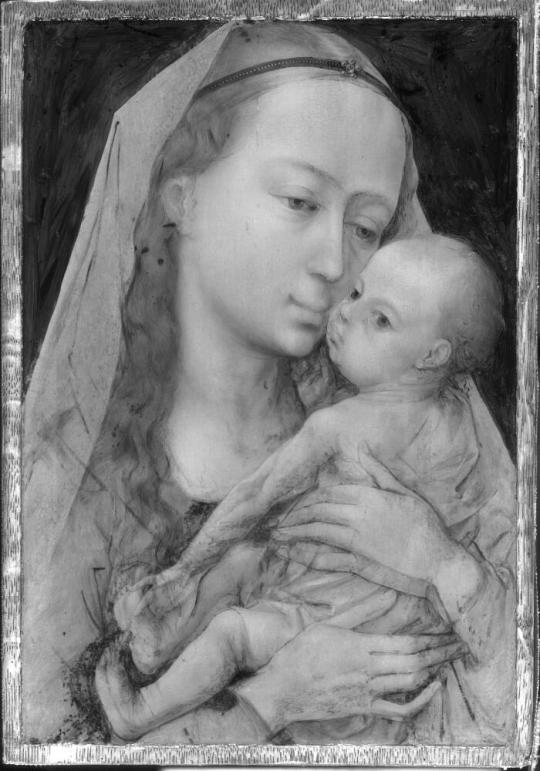

Virgin and Child

Frame: 15 1/4 × 11 7/8 in. (38.7 × 30.2 cm)

Ainsworth, Maryan. “‘A la façon grèce’: The Encounter of Northern Renaissance Artists with Byzantine Icons.” In Byzantium: Faith and Power (1261–1557), edited by Helen C. Evans, 545–55. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004.

Beenken, H. Rogier van der Weyden. Munich: F. Bruckmann, 1951.

Belting, Hans. Bild und Kult. Eine Geschichte des Bildes vor dem Zeitalter der Kunst. Munich: C. H. Beck, 1990. Translated as Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image before the Era of Art. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994.

Bowron, Edgar Peters, and Mary G. Morton. Masterworks of European Painting in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press in association with the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2000.

Châtelet, Albert. Rogier van der Weyden: Problèmes de la vie et de l’oeuvre. Strasbourg: Presses universitaires de Strasbourg, 1999.

Davies, Martin. Rogier van der Weyden: An Essay, with a Critical Catalogue of Paintings Assigned to him and to Robert Campin. London: Phaidon, 1972.

De Vos, Dirk. “De Madonna-en-Kindtypologie bij Rogier van der Weyden en enkele minder gekende flemalleske voorlopers.” Jahrbuch der Berliner Museen 13 (1971): 60–161.

De Vos, Dirk. Hans Memling: The Complete Works. Ghent: Ludion, 1994.

De Vos, Dirk. Rogier van der Weyden, The Complete Works. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1999.

Destrée, Jules. Rogier de la Pasture-van der Weyden. Paris and Brussels: G. van Oest, 1930.

Dunbar, Burton L. Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. German and Netherlandish Painting 1450–1600. Kansas City, Missouri: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in association with the University of Washington Press, 2005.

Evans, Helen C., ed. Byzantium: Faith and Power (1261–1557). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004.

Friedländer, Max J. Der altniederlandische Malerei II: Rogier van der Weyden und der Meister von Flèmalle. Berlin: Paul Cassirer, 1924. Translated as Early Netherlandish Painting II: Rogier van der Weyden and the Master of Flémalle. New York: Praeger, 1967.

Girault, Pierre-Gilles. “Trois ‘petits maîtres’: la formation du Maître de Saint Gilles, du Maître de la Légende de sainte Lucie au Maître au Feuillage brodé.” In Le Maître au Feuillage brodé: Démarches d’artistes et methods d’attribution d’œuvres à un peintre anonyme des anciens Pays-Bas du XVe siècle / The Master of the Embroidered Foliage: Artists’ processes and attribution methods to an anonymus [sic] flemish [sic] painter of the XVth century, edited by F. Gombert and D. Martens. Lille: Librairie des Musées, 2007.

Harbison, Craig. Jan van Eyck: The Play of Realism. London: Reaktion Books, 1991.

Held, Julius. Review of Early Netherlandish Painting: Its Origins and Character, by Erwin Panofsky. The Art Bulletin 37 (1995): 205–34.

Hulin de Loo, G. “Weyden (Rogier de la Pasture, alias Van der).” Biographie nationale publiée par l’Académie royale des sciences, des lettres et des Beaux-Arts de Belgique 27 (1938).

Klein, Peter. “The Differentiation of Originals and Copies of Netherlandish Panel Paintings by Dendochronology.” In Dessin sous-jacent et pratiques d’atelier: Le dessin sous-jacent dans la peinture, Colloque VIII, 8-10 septembre 1989, edited by Roger Van Schoute and Hélène Verougstraete-Marcq, 29–42. Louvain-la-Neuve: Collège Erasme, 1991.

Klein, Peter. “Dendochronological analyses of panels of Hans Memling and his contemporaries.” In Memling Studies: Proceedings of the International Colloquium (Bruges, 10–12 November 1994), 287–95. Leuven: Peeters, 1997.

Kolb, Karl. Elëusa-2000 Jahre Maddonenbild. Tauberbischofsheim: Wig-Verlag, 1968.

MacBeth, Rhona, and Ron Spronk. “A Material History of Rogier’s St. Luke Drawing the Virgin: Conservation Treatments and Findings from Technical Examinations.” In Rogier van der Weyden, St. Luke Drawing the Virgin: Selected Essays in Context, edited by Carol J. Purtle. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 1997.

Marzio, Peter C. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston: A Permanent Legacy. New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1989.

Marzio, Peter C., with the staff of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Masterpieces from the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Director’s Choice. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Catalogue of the Edith A. and Percy S. Straus Collection. Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1945, no. 27.

Panofsky, Erwin. Early Netherlandish Painting: Its Origins and Character. Vol. 1. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1953.

Périer-D’Ieteren, Catheline. “Une copie de Notre-Dame de Grâce de Cambrai aux Musées royaux des Beaus-Arts de Belgique à Bruxelles.” Bulletin Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique 17, 2/4 (1968): 111–14.

Périer-D’Ieteren, Catheline. “Rogier van der Weyden, his Artistic Personality and his Influence on Painting in the XVth Century.” In Rogier van der Weyden – Rogier de le Pasture, Peintre official de la Ville de Bruxelles, Portraitiste de la Cour de Bourgogne, 41–55. Brussels: Musée Communal de Bruxelles, Maison du Roi, 1979.

Périer-D’Ieteren, Catheline. “L’Annonciation du Louvre et la Vierge de Houston sont-elles des œuvres autographes de Rogier van der Weyden?” Annales d’Histoire de l’Art et d’Archéologie 4 (1982): 7–26.

Rolland, Paul. “La Madone Italo-Byzantine de Frasnes-lez-Buissenal.” Belgisch Tijdschrift voor Oudheidkunde en Kunstgeschiedenis 17 (1948): 97–106.

Schabacker, Peter H. Petrus Christus. Utrecht: Haentjens Dekker & Gumbert, 1974.

Schöne, W. Dieric Bouts und seine Schule. Berlin and Leipzig: Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft, 1938.

Sterling, Charles. La peinture médiévale à Paris 1300–1500. Vol. 2. Paris: Bibliothèque des Arts, 1990.

Tovell, Ruth Massey. Roger van der Weyden and the Flémalle Enigma. Toronto: Burns and MacEachern, 1955.

Winkler, Friedrich. Der meister von Flémalle und Rogier van der Weyden: Studien zu ihren Werken und zur Kunst ihrer Zeit mit mehreren Katalogen zu Rogier. Strasbourg: Heitz, 1913.

ProvenancePrivate collection, Hungary; [Paul Cassirer, Amsterdam, by 1924]; Fritz Hess collection, Berlin; [Hess Collection sale, Lucerne, Paul Cassirer and Theodore Fischer, September 1, 1931, lot 1]; purchased by [Strölin, Switzerland]; [Arnold Seligmann, Rey & Co., Inc., Paris and New York]; purchased by Percy S. Straus, December 29, 1931; bequeathed to MFAH, 1944.Rogier van der Weyden, born in Tournai around 1399, was the most influential Northern artist of the fifteenth century; his many works were copied and his style was imitated by artists for a century after his death. Rogier trained with Robert Campin in Tournai in 1427, but Campin was likely not his first teacher, as Rogier is already referred to as “master” in a document of 1426.1 By 1432 he was working on his own. In the mid-1430s, Rogier’s fortunes took a decisive turn when the city of Brussels actively courted him to relocate and become the city’s official painter, a position they created specifically for him.2

Rogier entered professional life just as Flemish art had been transformed by the detailed observation and startlingly life-like realism of Robert Campin and Jan van Eyck. Rogier contributed to these innovations a powerful emotional expressiveness rooted in deep Christian piety. The increasingly popular Devotio Moderna emphasized personal engagement with and emotional response to the life and Passion of Christ. In large-scale altarpieces, Rogier’s painted saints, whose intent gazes, strained mouths, and twisted poses proclaim their suffering, evoke analogous responses in viewers. Rogier also painted many small panels for personal devotion. The Straus Virgin and Child is among these, and it radiates the emotional intensity for which Rogier’s works are justly famed.

Small devotional panels like this one were produced in large numbers by Rogier and his contemporaries. They were meant for use in the home, or perhaps to be carried to a chapel for worship. They were often joined in a diptych with a panel depicting the patron in prayer. It is possible that at some point in its history, this panel was part of such a diptych.

The Virgin tenderly holds the infant Christ Child, bending her head to touch her cheek to his. The Child squirms in her grasp, gently clutching a strand of her hair and playing with his foot. The simplicity of the subject belies the artist’s skill in composing the scene, its liveliness articulated within a remarkably small and shallow space. The attention to line throughout introduces a subtle and elegant rhythm to the embrace and lends a graphic solidity to the forms.3 Observe, for example, the continuation of the arc of the Virgin’s jawline along her outstretched left thumb and forearm, crossing the curve that extends from the meeting of their cheeks along the Child’s arm.

Images of the Virgin and Child had been popular as a devotional subject since the early Middle Ages. Rogier’s composition was informed particularly by the thirteenth-century Italian Notre Dame de Grâce (fig. 23.1), brought from Italy and installed in the Cambrai Cathedral in 1452.4 From this model, Rogier took the Child’s reach toward the Virgin’s chin and their cheek-to-cheek touch. Rogier intensified their emotional connection by tightening the Virgin’s grasp on the Child and directing her gaze toward him, rather than the viewer. Moving the whole composition, with its depictions of soft fabrics, wispy hair, and blushing skin, closer to the picture frame draws the viewer into the pair’s intimacy.5 The Cambrai Madonna was a hugely popular image in the fifteenth century and was copied many times, often quite faithfully. For Rogier, the Byzantine icon was more inspiration than direct source, as he transforms the icon in its other-worldly, gold-grounded space into an image of the devotion of a real mother to her son.6

Infrared reflectography shows that Rogier shifted the position of the Virgin’s hands and the Christ Child’s feet during the course of painting, enhancing the delicate play of lines connecting mother and child (fig. 23.2). Such subtle changes to the composition, especially the adjustment of the hands, are typical of Rogier’s working method.7 The panel has suffered much damage; abrasion and repainting having obscured most of the original surface. The poor condition and retouching have led the panel’s attribution to be doubted in the past, but recent scholarship accepts the work as autograph.8

—Michelle Packer

Notes

1. Dirk De Vos, Rogier van der Weyden, The Complete Works (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1999), 47, 50. De Vos argues the title maître, or “master,” may have been a legal prerequisite for Rogier’s activity as a professional painter rather than a recognition of skill or completion of training.

2. De Vos, Rogier van der Weyden, 53. The position did not exist before being offered to Rogier, and was eliminated following his death in 1464.

3. Max J. Friedländer, Der altniederlandische Malerei II: Rogier van der Weyden und der Meister von Flèmalle (Berlin: Paul Cassirer, 1924), translated as Early Netherlandish Painting II: Rogier van der Weyden and the Master of Flémalle (New York: Praeger, 1967), 24; De Vos, Rogier van der Weyden, 315; and Lorne Campbell, Rogier van der Weyden: Master of Passions (Leuven: M-Museum, 2009), 376–79.

4. Campbell, Rogier van der Weyden: Master of Passions, 378, no. 2. Rogier was working in Cambrai in the mid-1450s.

5. As observed by Max J. Friedländer, Der altniederlandische Malerei II: Rogier van der Weyden und der Meister von Flèmalle (Berlin: Paul Cassirer, 1924), translated as Early Netherlandish Painting II: Rogier van der Weyden and the Master of Flémalle (New York: Praeger, 1967), 22. “Space, views, embellishments—these he felt to be diversions that detracted from ecclesiastical tranquility and spiritual contemplation.”

6. Maryan Ainsworth, “‘A la façon grèce’: The Encounter of Northern Renaissance Artists with Byzantine Icons,” in Byzantium: Faith and Power (1261–1557) (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004), 554, refers to such Netherlandish images of the Virgin and Child as “living icons.”

7. Rhona MacBeth and Ron Spronk, “A Material History of Rogier’s St. Luke Drawing the Virgin: Conservation Treatments and Findings from Technical Examinations,” in Rogier van der Weyden, St. Luke Drawing the Virgin: Selected Essays in Context, ed. Carol J. Purtle (Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 1997), 110–13.

8. The attribution to Rogier was doubted by Jules Destrée, Rogier de la Pasture-van der Weyden (Paris and Brussels: G. van Oest, 1930); and Erwin Panofsky, Early Netherlandish Painting: Its Origins and Character, vol. 1 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1953). It was rejected by H. Beenken, Rogier van der Weyden (Munich: F. Bruckmann, 1951); and Catheline Périer-D’Ieteren, “Une copie de Notre-Dame de Grâce de Cambrai aux Musées royaux des Beaus-Arts de Belgique à Bruxelles,” Bulletin Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique 17, 2/4 (1968): 111–14. However, Friedländer, Early Netherlandish Painting II; Martin Davies, Rogier van der Weyden: An Essay, with a Critical Catalogue of Paintings Assigned to him and to Robert Campin (London: Phaidon, 1972); Craig Harbison, Jan van Eyck: The Play of Realism (London: Reaktion Books, 1991); Albert Châtelet, Rogier van der Weyden. Problèmes de la vie et de l’oeuvre (Strasbourg: Presses universitaires de Strasbourg, 1999); Dirk De Vos, Rogier van der Weyden, The Complete Works (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1999); and Maryan Ainsworth, “‘A la façon grèce’: The Encounter of Northern Renaissance Artists with Byzantine Icons,” in Byzantium: Faith and Power (1261–1557) (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004), accept the work as autograph. For a description of changes made to the composition in the course of painting, see Périer-D’leteren, “Une copie de Notre-Dame,” 19–22.

Comparative Images

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has made every effort to contact all copyright holders for images and objects reproduced in this online catalogue. If proper acknowledgment has not been made, please contact the Museum.