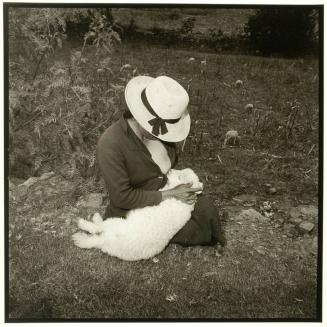

Clementine Hunter

Clementine Hunter

American, 1886–1988

ActiveLouisiana, United States

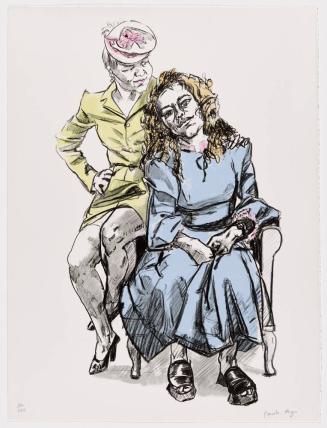

BiographyBiography from AskART:Often referred to as "the black Grandma Moses," Clementine Hunter painted boldly colored images in folk art style of plantation life in Louisiana. Her subjects included everyday activities such as doing laundry and festive events including weddings, dances, and church going. She also did a number of Christian religious subjects.

She was born at Hidden Hill Plantation near Natchitoches, Louisiana and lived there the remainder of her life, one-hundred-one years, raising seven children and working in the fields. She attended a local Catholic school, but quit at a young age and never learned to read or write. At age sixteen, she moved to nearby Melrose Plantation where she worked for many years as a field hand.

Her first husband was Charlie Dupree, who died in 1914, and ten years later she married Emanuel Hunter and moved into the plantation house where she was in charge of the domestic work. Becoming associated with the plantation mistress, Ms. Cammie Henry, changed Hunter's life. Henry, was an archivist and artist who actively encouraged the arts. She opened her home to artists and authors who needed a quiet place to work. It was at Melrose that Hunter first began her production of hand made quilts, dolls and lace curtains.

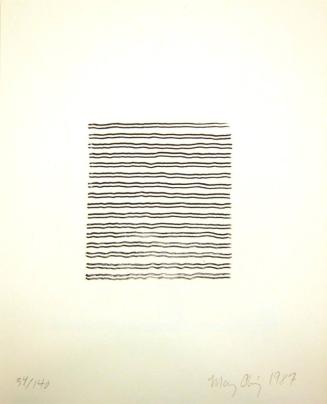

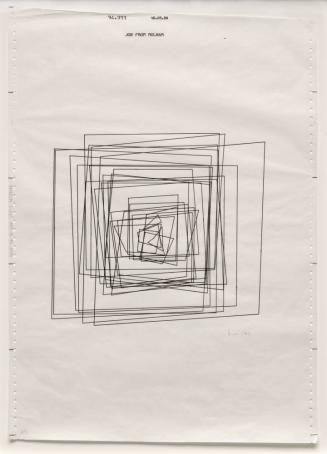

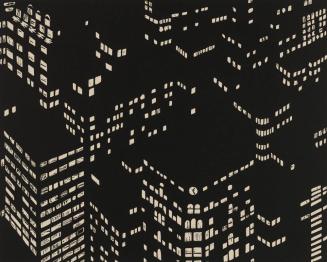

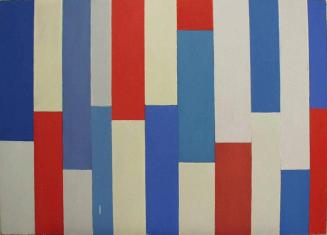

Meeting artist friends of Ms. Henry, Hunter met many people in the art world and was especially influenced and promoted by Francois Mignon who was an artist-in-residence at the plantation. In 1946, under his direction, she did her first work, a plantation baptism scene, from a few partially used tubes of oil paint on a window shade that he provided. Another supporter at that time was James Register, also an artist-in- residence, and he obtained a Julius Rosenwald Foundation Grant for her. He encouraged her to do abstract art, which she did while letting him choose the titles.

But she preferred the folk art style. From that time, she was prolific, and created over four-thousand scenes of plantation life on whatever materials were available from scrap wood to paper bags. She thinned her oil paint so much it resembled watercolor. She sold many of her first works for a dime or quarter to pay for her husband's medical treatment. In the early 1950s, her work began to attract widespread attention, and in 1956, the New Orleans Museum of Art honored her with a one-woman show. This event was the first time a Louisiana Museum had a show for an African-American person, but she had to view the event alone because blacks were not allowed entry with whites.

Person TypePerson