Melvin Sokolsky

Melvin Sokolsky

American, 1933–2022

Birth placeNew York City, New York, United States

Death placeBeverly Hills, California, United States

BiographyDied August 29, 2022. New York Times article here: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/14/fashion/melvin-sokolsky-dead.htmlMelvin Sokolsky, Surrealist Fashion Photographer, Dies at 88

nytimes.com/2022/09/14/fashion/melvin-sokolsky-dead.html

Alex Williams, September 14, 2022

Melvin Sokolsky, a photographer who pushed boundaries by creating fantastical tableaus for fashion bibles like Harper’s Bazaar that seemed to defy both gravity and logic, died on Aug. 29 at his home in Beverly Hills, Calif. He was 88.

The death was confirmed by his son, Bing.

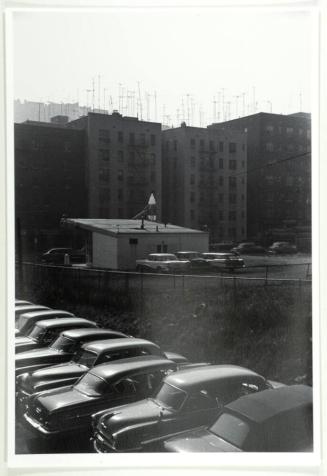

Mr. Sokolsky was an untrained photographer who grew up in a tenement on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, snapping pictures with his father’s box camera as a child. His career in fashion photography imbued cool couture style with high-art surrealism, spanning the explosion of color and creativity of the 1960s. In 1969, he moved on to directing and shooting television commercials, collecting more than 25 Clio Awards and directing memorable spots like Ricardo Montalbán’s “Corinthian leather” Chrysler ads.

Regardless, it was his decade in magazines that became his legacy, helping to redefine what was possible in fashion photography — a period when he produced memorable portraits of Hollywood stars like Mia Farrow and Natalie Wood and earned praise from top models like Twiggy. Many of his images were later shown in galleries and museums, including the Louvre in Paris, the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Getty in Los Angeles.

“He possessed all the elements to be a successful photographic artist,” said David Fahey, a founder of Fahey/Klein Gallery, which represented Mr. Sokolsky in Los Angeles. “He was an ideas man, and he was also the consummate technician. He always had a point of view that challenged the norm.”

[Image] Mr. Sokolsky in a photo titled “Simone + Me,” with the model Simone D’Aillencourt, published in Harper’s Bazaar in 1960. Credit...Melvin Sokolsky/Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

When Mr. Sokolsky started shooting for Harper’s Bazaar in 1959, “Richard Avedon was the leading photographer of the Bazaar, taking classic high-society pictures,” he said in a 2019 interview published by the Holden Luntz Gallery in Palm Beach, Fla. “I was new at the magazine and considered the kid.”

And he was a rebellious one.

At one early shoot, Mr. Sokolsky went gritty, photographing designer-draped models against peeling walls in tenements. Bazaar rejected the shots; one editor, he recalled, told him, “Subscribers that read the Bazaar would not recognize the places where you’re putting our fashions.”

For Mr. Sokolsky, that was the point. It took Diana Vreeland, who was then the magazine’s fashion editor, to lobby for publishing the photos.

“When the pictures ran, many subscribers wrote letters: ‘Who is this new photographer?’” Mr. Sokolsky recalled in the Holden Lunt interview. “Finally, I found an audience.”

His flights of whimsy earned him even more fame. In the buttoned-up early ’60s, he was already producing images that seemed to foreshadow the psychedelic era to follow — not to mention Photoshop. His dreamlike “Fly” series for Bazaar in 1965 featured icily chic models clad in Dior soaring over the streets of Paris or over the tabletops of elegant paneled restaurants filled with well-heeled diners.

An art lover who drew inspiration from painters as diverse as Bosch, Vermeer and Picasso, Mr. Sokolsky churned out arresting images that seemed as appropriate for gallery walls as they were for fashion glossies.

“He told me, ‘If you’re going to steal from somebody, steal from the masters,’” Bing Sokolsky said in a phone interview.

One series from 1962 posed models on a giant wooden chair, making them appear to be the size of Barbie dolls. In another series he blended models’ faces with flower petals; in yet another he superimposed images of a model’s face from multiple perspectives — fashion’s answer to Cubism.

[Image] From Mr. Sokolsky’s dreamlike “Fly” series, shot for Harper’s Bazaar in 1965. Credit...Melvin Sokolsky/Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

Perhaps none of his work had the impact of his famous “bubble” series. In December 1962, the Bazaar editor Nancy White invited him to shoot the collections for the following spring. Mr. Sokolsky proposed a seemingly absurd idea: a series placing a model in what appeared to be a giant soap bubble in or over familiar locations around Paris. (The bubble was actually a giant Plexiglas orb suspended by a thin cable that was later edited out.)

“In my imagination, when I built the bubble for the Bazaar shoot, I secretly saw it as a Sokolsky aircraft that could fly anywhere on an engine built into one of the rings that contain the bubble hemispheres,” he said in the Holden Luntz interview. “It was not a girl captured in a bubble. It was a woman at the helm of her spaceship.”

He reprised the concept in 2015, producing a bubble shoot with Jennifer Aniston for Bazaar.

Not everyone was charmed by the idea — at least not at first. Ms. White considered it unworkable. Mr. Avedon dismissed it as well, saying that Mr. Sokolsky would never get the ungainly sphere off the ground.

That angered Mr. Sokolsky. “‘Why is God doing this to me?’ I thought,” he recalled in a 2019 interview with Wraparound, a photography and design magazine. “And I began to realize, in many ways, the world is petty. There are no gods.”

But that was all the more reason to do it his way.

Melvin Sokolsky was born on Oct. 9, 1933, in Manhattan to David and Yetta (Kleinberg) Sokolsky, the older of two sons. His father was a pressman at a printing company, and money was tight. When his father was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, Melvin, at 16, took a job at the post office to help support his family.

An avid bodybuilder, he went on to market a line of form-fitting T-shirts and shorts, placing ads in the back of fitness magazines, his son said. He also invented a coin-operated box outfitted with sun lamps for gyms, so fitness enthusiasts could bronze themselves, quarter by quarter.

Still, his camera was never far from his side. Early efforts to secure jobs in commercial photography went nowhere. “It was in the late ’50s,” Mr. Sokolsky told Wraparound. “I was ‘too artsy.’”

His big break came in 1959, when an art director working on a fur company account tossed him a coat and said, “Surprise me,” Mr. Sokolsky recalled. He produced a hauntingly beautiful image of a fur-wrapped model that evoked 1920s glamour. The image appeared in a magazine, crediting him by name. Soon after, Henry Wolf, the art director for Bazaar, called him with an offer to shoot for that magazine.

[Image] When Mr. Sokolsky first proposed his idea for the “bubble” series, editors were unimpressed. “It was not a girl captured in a bubble,” he said. “It was a woman at the helm of her spaceship.” Credit...Melvin Sokolsky/Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

As the 1960s drew to a close, however, Mr. Sokolsky searched for a new challenge and started directing commercials. He became a heavyweight of the ad trade, conceiving and directing hit campaigns like the “I’m a Pepper” series for Dr Pepper and a long-running campaign for Coors beer featuring the actor Mark Harmon. (He took photographs for those campaigns as well.)

While he continued to do occasional shoots for magazines like Bazaar, GQ and Vogue Italia, Mr. Sokolsky never considered his move to 30-second commercial spots a step down.

For him, “it wasn’t so much changing careers,” Bing Sokolsky said. “It was all about telling the story. You can tell great stories with a single image, but you can tell even better stories when you’ve got a moving image.”

In addition to his son, Mr. Sokolsky is survived by his brother, Stanley. His wife, Button (Whelan) Sokolsky, died in 2016.

Mr. Sokolsky saw art, regardless of the medium, as acts of experimentation not bound by the rules of genre.

“When you experiment, within that experiment there’s a place that I call discovery,” he told Wraparound. Art, he added, “is about trying things and discovering things you never noticed before and letting yourself go there.”

When asked how he knew when an experiment was working, his answer was, perhaps fittingly, tinged with the surreal:

“You get that invisible cold icicle that goes through your brain without penetrating your skin.”

Person TypePerson

American, born France, 1868–1946