- Portrait of a Boy

Explore Further

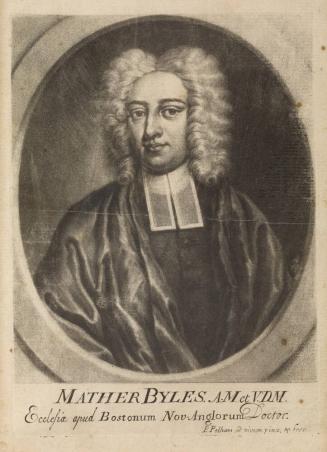

For almost twenty-five years, the unrivaled portraitist of the American colonies was John Singleton Copley, a Boston painter whose artistic vision, technical mastery, and high ambition set a standard for the encouragement and development of the arts of North America. Of humble origins, the son of Irish immigrants and tobacco shopkeepers, Copley rose to fame and fortune, providing spectacular portraits of Boston’s largely mercantile and upwardly mobile elite, clergymen, military leaders, Whigs, Tories, and such political figures as Samuel Adams, Paul Revere, and John Hancock. Trained by his stepfather Peter Pelham (see B.61.69), a mezzotint engraver from London, and further educated by the theoretical and anatomical treatises he eagerly read, Copley aspired to be a history painter, by tradition the highest genre of painting an artist could practice. History painting held little interest for the pre-Revolutionary colonies, however, so Copley focused his talent on painting “likenesses,” producing over three hundred portraits before leaving the colonies on the eve of the Revolutionary War in 1774.

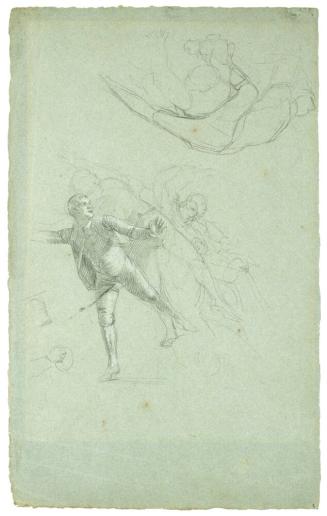

Bold color, dramatic chiaroscuro, and a legendary facility for painting forms convincingly—faces as well as finery—are the characteristic features of Copley’s portraits throughout his colonial career. Earlier works, such as the Portrait of a Boy, demonstrate his knowledge and use of the props, costumes, and settings of eighteenth-century English mezzotints. In later works, as in the Portrait of Mrs. Paul Richard (see B.54.18), Copley relinquishes the exuberance of his earlier works, preferring to portray sitters emerging from dark, monochromatic backgrounds with greater value contrasts and more somber tones, which tends to heighten the psychological presentation of the sitter. At the time Copley painted this portrait, he had absorbed the Rococo ebullience of Joseph Blackburn (act. 1752–c. 1778, see B.2016.4) and had mastered a variety of compositional elements from his predecessors Robert Feke (see B.71.81) and Joseph Badger (B.53.13). Rich color, dramatic chiaroscuro, and a playful and generous use of props characterize many works of this period, in which the artist was quickly establishing himself as the most astonishing and skillful artist the colonies had ever seen.

The identity of the boy holding a battledore continues to elude scholars. On the basis of its status as a large, full-length portrait, one can speculate that the boy was probably the firstborn son and heir of a wealthy and socially ambitious family. Its profusion of props—a shuttlecock to accompany the battledore, a braid-trimmed tricorn hat tossed to the ground, a marble or stone architectural element borrowed from a Continental or English portrait mezzotint—and complex landscape details, including a stream in the immediate foreground dotted with plants and a hilly landscape and vivid sunset in the background, point to the artist’s considerable effort to impress his patrons with his knowledge of Continental and English prototypes, as well as to flatter the sitter and his family by loading his image with objects associated with aristocratic portraits. Furthermore, the sitter’s posture, derived ultimately from antique sculpture and popularized in the mid-eighteenth century in portraits by Thomas Hudson and Allan Ramsay, suggests nonchalance and easy confidence, esteemed characteristics of behavior endorsed by etiquette books of the period. His jaunty pose is reinforced by the dapper rose pinned to his jacket, a prop that is unique in Copley’s oeuvre. Pentimenti reveal that Copley initially portrayed the sitter holding a book, but changed the prop to a battledore and shuttlecock, an attribute with more youthful associations, and one that connects Copley’s portrait with the English artist Francis Cotes’s portraits of aristocratic children with kites or cricket bats.

The first written record of the portrait appeared in 1884 at the Francis Alexander sale at Leonard and Co., Auctioneers, Boston. The catalogue stated that the portrait depicted the son of John Hancock by Copley (this mistaken identity persisted until 1938), and that it once belonged to Moses Kimball, who bought the portrait at the sale of the Portsmouth Museum, along with portraits of John and Dorothy Quincy Hancock. Nothing of this catalogue description can be substantiated.

Recent research plausibly suggests that the sitter is a member of the Bourne, Gorham, or, most likely, Swett families. Francis Alexander, an American artist living in Florence, probably did not purchase the painting from Moses Kimball or anyone else at all, particularly since he was a collector of Italian Old Masters, not eighteenth-century American portraitists. Rather, the portrait was likely an ancestral painting belonging to Alexander’s wife, Lucia Gray Swett Alexander (1814–1916), who had inherited about 1866 another Copley portrait, of Mrs. Sylvanus Bourne (c. 1766, MMA), which, like the Bayou Bend portrait, descended to her daughter before both portraits were distributed among cousins. Lucia likely inherited both portraits from her father, Colonel Samuel Swett (1782–1866), of Boston. Samuel Swett probably inherited them from his parents, John Barnard Swett and Charlotte Boume Swett (b. 1760), of Newburyport. Inasmuch as Charlotte Bourne Swett inherited the portrait of her grandmother, Mrs. Sylvanus Bourne, it is possible that either she inherited the Bayou Bend portrait at the same time (and the sitter represents a member of the Gorham or Bourne families), or, more likely, the portrait belonged to her husband John Barnard Swett and represents a member of the Swett family.

Related examples: In terms of technique, this portrait relates to Copley, Mary and Elizabeth Royall, c. 1758, MFA, Boston. Bayou Bend’s portrait also relates to Copley’s portraits of children: Thomas Aston Coffin, c. 1757–59, Munson-Williams-Proctor Institute, Utica, New York; Young Lady with a Bird and Dog, 1767, Toledo; Mary Elizabeth Martin, 1771, Addison Gallery of American Art, Andover, Massachusetts; and Daniel Crommelin Verplanck, 1771, MMA. Bayou Bend’s portrait is the last in which the artist used the prop of the battledore and shuttlecock, having used it previously in his portrait of Thomas Aston Coffin. The prop was not uncommon in English portraiture. Copley may have been the first colonial portraitist to introduce this prop, followed by such artists as William Williams, in his portrait of Stephen Crossfield, c. 1775, MMA, and John Green, in his portrait of Clayton Trott, c. 1780, Hereward Trott Watlington collection. The jaunty pose of the sitter, in which he leans against a marble element with his other arm resting on an outthrust hip, also appears in Copley’s George Scott, 1755–57, the Brook, New York; Moses Gill, 1764, RISD; Thaddeus Burr, c. 1758–60, Saint Louis Art Museum; Epes Sargent, c. 1760, NGA; among other portraits of the 1760s.

Book excerpt: David B. Warren, Michael K. Brown, Elizabeth Ann Coleman, and Emily Ballew Neff. American Decorative Arts and Paintings in the Bayou Bend Collection. Houston: Princeton Univ. Press, 1998.

ProvenanceThe sitter, probably a member of the Swett, Bourne, or Gorham families; probably to Colonel Samuel Swett (1782–1866), Boston; probably to his daughter Mrs. Francis Alexander (Lucia Gray Swett, 1814–1916), Florence, Italy; to her daughter Esther Frances ("Francesca", 1837–1917), Alexander (1837-1917), Florence, Italy; to her cousin Charlotte Bartlett Williamina Gray Hallowell, West Medford, Massachusetts; purchased by the Honorable Alvan Tufts Fuller (1878–1958), Boston; [Vose Galleries, Boston]; purchased by Miss Ima Hogg, 1954; given to MFAH.

Exhibition History"The Summer Exhibition of Colonial Portraits," Vose Galleries, Boston, 1926

"Colonial Portraits from the Collection of Miss Ima Hogg," Music Hall, Houston, 1957

"The Masterpieces of Bayou Bend, 1620-1870", Bayou Bend Museum of Americana at Tenneco, Houston, TX, September 22, 1991–February 26, 1993

"John Singleton Copley in America," organized by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, at The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, February 4–April 28, 1996 (Houston venue only).

Inscriptions, Signatures and Marks

Cataloguing data may change with further research.

If you have questions about this work of art or the MFAH Online Collection please contact us.