Robert Heinecken

Robert Heinecken

American, 1931–2006

ROBERT HEINECKEN 1931-2006

In the mid 1960s Robert Heinecken wrote,

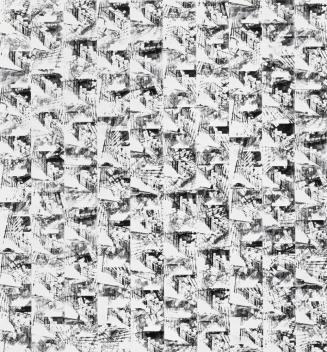

"We constantly tend to misuse or misunderstand the term reality in reference to photographs. The photograph itself is the only thing that is real, that exists…. (There is a vast difference between taking a picture and making a photograph.)" This parenthetical phrase is, typically, a loaded Heineckism -- always open to interpretation and thus leading to new ideas, new visions, new images, and new possibilities.

In 1976 I wrote of him:

"Heinecken asks: 'Why does a man construct such elaborate facades behind which he persists in living a lie? Why is the lie not his ideal, his image, his truth?' Not having an answer, he resigns himself to making poignant reference to the problem. What is commonly rationalized, avoided, obscured or discounted is the stuff of his philosophy, which issues forth investigations of religion, sex, politics or education.

"He uses existing photographs … and their reproductions because they have littered the world and our minds with unlimited examples of every conceivable image of truth, beauty, banality, eroticism, brutality, pornography, consumerism, political idea, personality, idol, and ideal. Indeed one is hard put to name anything that has not been replaced by a photographically derived image. His recycling of these images makes this astounding point before making any other. Heinecken knows the photograph is not real. He also knows that most of us still believe it is… The camera eye is lusty and insatiable, a perfect match for Heinecken's eye."

Robert Heinecken was unique, extraordinary -- in the true sense of that word. Intelligent, tough, critical, and penetrating in his perception of art, media, literature, and people. He understood your being as well as your work. Colleagues and students were the beneficiaries -- often at the end of an intense experience/exchange. But he was also soft, easy, generous, committed to giving to others. And he steadfastly maintained a rich sense of humor about his own as well as others' foibles. He broke the mold; he turned the tide of 20th-century photography. He called for disrupting what was becoming a repetitious and constraining aesthetic; he asked for manipulation -- a manipulation that had as its goal something greater than breaking the mold. He asked for manipulation as a way to the deliverance of an individual artist's (rather than a medium's) unique vision. The point of his argument was, whether following or breaking what others considered the restrictions of a medium, the artist must make them do what was necessary to a unique inner vision, idea, goal. Don't break the rule simply to break the rule. That is a statement as limited as that which blindly follows the rule. Break the rule that limits you to the rule rather than opens you to the idea.

He played by a strict code (perhaps a result of being the son and grandson of ministers; or, perhaps the result of being a Marine fighter pilot!). He brought an extraordinary discipline to his work, his teaching, and to his life. And he expected no less from his students and colleagues. His commitment to skill and craft is evidenced in his work and in his words.

There is no better evidence of this than what can be seen in the evolution of the students, the activities, the facilities, and the outreach of the teaching, collecting, and multifaceted programs of the Department of Art at UCLA where for so many years, Heinecken was a fixture both figuratively and actually. His passionate devotion to education was as deep, as influential, and as meaningful, as it was to his art. And its effect reached from Los Angeles to Boston at the critical moment in the proliferation of photographic programs in universities across the continent.

He brought a different vision of what was possible. He brought a tough set of ideas about form and content; about thinking and making, about connecting with other issues and peoples of his time. The title of one of his series -- Cliché Vary -- conveys a sense of his imagination, his vision: investigate clichés, vary them, break them down, understand them; and make something new which conveys both the source and the multifaceted meanings and potential lying within. And be competitive, not for the sake of competition, but for the sake of a greater manifestation of a unique presentation, the uniqueness of which causes others to expand their own potential. Heinecken demonstrated this in an amazingly broad artistic output, in an amazingly broad group of students, and at the card table, the Ping-Pong table, and the billiard table. He demonstrated this in all aspects of a non-stop life.

He loved being called a guerrilla artist (and teacher!). He loved pushing the public's buttons -- whether about the Vietnam War, sexuality, politics, mass media (for example, the growing theatricality of "The News," or the artificiality of fashion and celebrity). But he never let go of (nor let friend or viewer miss) his dedication to mastery of the craft and form via which he sent us his messages. And there is no better example of this than his endlessly fascinating re-makings of the ubiquitous 8-1/2X11 magazines, from NEWSWEEK to HUSTLER, from historical essay to full-page advertisement, from art reproduction to blatant centerfold pornography; from immediate crass materialism to ancient Asian symbolism. Always these projects contained evidence of his intellect; an intellect that was as evident in conversation on the lawn, as it was in his use of language in print or at the podium. He could not suffer fools lightly or heavily, in the world or in the classroom. But he could and did make himself available completely to his students, his colleagues, and his friends.

Heinecken was an extraordinary and prolific maker of images through which he presented the results of his penetrating perception of, and his visual interpretation of, the world of the second half of the 20th century. In that committed life he played a central and importantly influential role in what he might term "the transmogrification" of photography. Indeed, some of us continue to wonder whether Heinecken, who rarely used a camera, was, in fact, a photographer. He used and made everything that can be included under the term visual -- which in our time, and in his terms, must be somehow photographically connected. Perhaps, "photographist" as coined by Arthur Danto and used in Heinecken's 1999 retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, is the more appropriate term.

Heinecken was one of the handful that parented Postmodernism in the visual arts. The culture of the art world has long since caught up (and largely forgotten its parentage). Nonetheless he was central to the opening up of eyes, and therefore minds, to the omnipresence and force of the contemporary visual world.

He asked for and gave the best -- as he worked to awaken us to the worst. His presence will be sorely missed.

Carl Chiarenza

May 19, 2006

Person TypePerson

American, 1914–1997