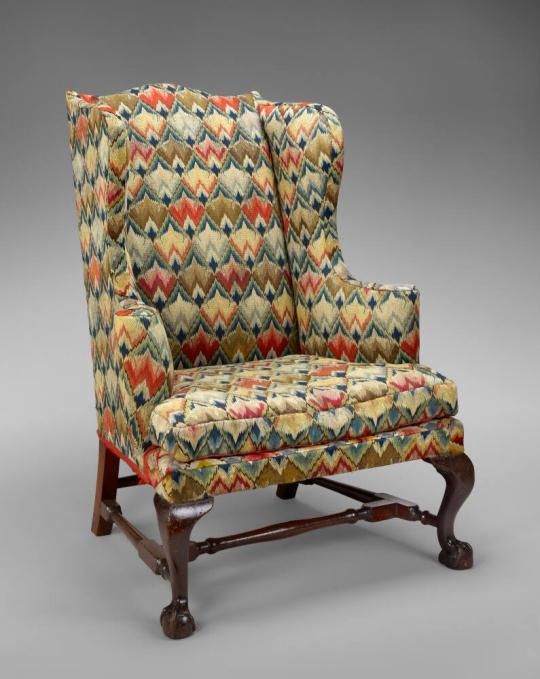

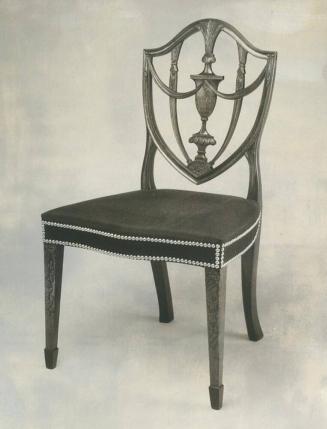

- Easy Chair

Explore Further

This colorful easy chair, complete with its vivid Irish stitch cover, is among the most highly prized survivals of eighteenth-century American upholstered furniture. It represents the contributions of several individuals: the needlewoman, who in all probability was not a professional but an upper-class lady whose husband had commissioned the frame; the chairmaker; and the upholsterer who constructed the foundation, attached the needlework, and made up the cushion.

The relatively undisturbed frame of this chair presents an extraordinary document of the outline and contours characteristic of colonial upholstery. The interior is fully stuffed to ensure its occupant the utmost comfort; by contrast, the exterior is thinly padded, resulting in a taut appearance. The back is upholstered with an English stamped harrateen of watered patterning with meandering band, butterflies, and flowers. Originally, the seams were concealed by welt and tape.

Upholstery work was the principal, and most logical, of all the decorative arts-related trades for a woman to pursue. In Philadelphia Ann King advertised the establishment of her own shop after having “the care of the Women’s work, in the Upholstery business, at Mr. John Webster’s, for near seven years.” There she made up mattresses, cord, and fringes, claiming distinction as “the first American tossel [tassel] maker that ever brought that branch of business to any degree of perfection in this part of the world.” In many respects the eighteenth-century upholsterer was the forerunner of the nineteenth- and twentieth-century interior designer. For Webster, King, and others in the upholstery trade, it offered the potential for a livelihood second only to that realized by the silversmith.

Technical notes: Mahogany; white pine (corner blocks), maple (seat rails). The upholstered frame could not be sampled. At the time of the chair’s purchase, Miss Hogg consulted Charles F. Montgomery regarding the upholstery’s conservation. It was agreed that Ernest LoNano would make minor repairs and clean the material. Miss Hogg wrote to John Walton requesting that LoNano complete the treatment without disturbing the upholstery. Surprisingly, she approved making up a new cushion using the needlework from the original so it would “fit the chair properly.” A radiograph indicates that LoNano removed the needlework from the frame, presumably to facilitate in the cleaning of the textile, but left the foundation largely undisturbed.

Related examples: American easy chairs with their original needlework upholstery intact are all of New England origin: Downs 1952, no. 74; Heckscher 1985, pp. 122–24, no. 72. Another chair retains its original worsted cover: Heckscher 1987a, pp. 98–103. Easy chairs with some of their original show cover in place include Antiques 54 (July 1948), p. 3; Passeri and Trent 1983, pp. 26A–28A; Cooke 1987, now at the MFA Boston (acc. no. 1994.267); Forman 1988, p. 366; Wood 1996, pp. 68–69, no. 29A. A Marlborough-legged Massachusetts easy chair is pictured in Antiques 90 (August 1966), inside cover.

Book excerpt: David B. Warren, Michael K. Brown, Elizabeth Ann Coleman, and Emily Ballew Neff. American Decorative Arts and Paintings in the Bayou Bend Collection. Houston: Princeton Univ. Press, 1998.

ProvenanceGillette estate, Oyster Bay, Long Island, New York; aquired by [John S. Walton, New York]; purchased by Miss Ima Hogg, November 10, 1960; given to MFAH, by 1966.

Exhibition History"The Masterpieces of Bayou Bend, 1620–1870", Bayou Bend Museum of Americana at Tenneco, Houston, TX, September 22, 1991–February 26, 1993

"American Made: 250 Years of American Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston," The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, July 7, 2012–October 15, 2013.

Inscriptions, Signatures and Marks

Cataloguing data may change with further research.

If you have questions about this work of art or the MFAH Online Collection please contact us.