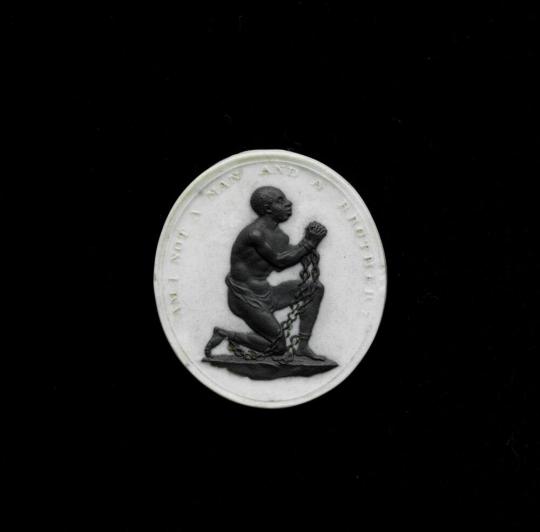

- Abolitionist Medallion

Explore Further

The British antislavery trade campaigns of the late 1700s produced the single most famous abolitionist image. Modeled by William Hackwood for Josiah Wedgwood in 1787, this medallion portrays an enslaved man kneeling in chains with clasped hands. The Society for the Abolition of Slavery in England adopted the design for its seal the same year, in which Wedgwood was a committee member. To persuade others of the rightness of their cause, the society selected the explicit wording “Am I Not a Man and a Brother” for use on its seal and, consequently, Wedgwood’s medallion. Before Englishmen and Americans could regard slaves as brothers, they would first have to consider them human beings.

Wedgwood donated the medallions to friends and supporters of the abolitionist cause. Precisely how many of the medallions were produced is uncertain, but it is thought to be in the hundreds. In 1807, Britain abolished the trade in enslaved people, and in 1833 abolished slavery in most of its colonies. In 1808, Thomas Clarkson, one of Britain’s leading abolitionists, recounted how the medallions came to be widely disseminated and publicly visible. Women, he reported, incorporated them into pendants, bracelets, and hairpins so that “the taste for wearing them became general.”

On the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, in February 1788, Wedgwood mailed Benjamin Franklin, the president of the Pennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery, a package written with the note, “a few Cameos on a subject which is daily more and more taking possession of men’s minds on this side of the Atlantic as well as with you.”

This image of the kneeling enslaved man would go on to be reproduced on plates, cups, patch boxes, metal tokens, pincushions, fabrics, and an antislavery broadside into the 1800s. It sought to engage ordinary Britons to petition for abolition, and it would become a staple of American abolitionist imagery.

Though the medallion’s purpose was to advance the abolitionist cause, the image itself is clearly the product of a narrow, paternalistic view. The enslaved man is depicted as deferential, powerless, subservient – essentially inferior and in need of assistance from white people.

Provenance[Timothy Millet Limited, London]; purchased by MFAH, 2022.

Inscriptions, Signatures and Marks

Cataloguing data may change with further research.

If you have questions about this work of art or the MFAH Online Collection please contact us.