After his early career in London, Thomas Gainsborough moved back to his native Sudbury in 1748–49 and lived in Ipswich by 1752, where both of his daughters were born. Around 1759, he moved to Bath, where he prospered as a portrait painter. However, his passion was the creation of landscapes, and he wrote to his friend William Jackson, “I’m sick of Portraits and wish very much to take my Viol da Gam [viola da gamba] and walk off to some sweet Village where I can paint Landskips.”1 He enjoyed the countryside surrounding Ipswich and then Bath, not returning to London until 1774, where he remained until his death in 1788.

Gainsborough’s obituarist, the Reverend Sir Henry Bate Dudley, wrote in 1788, “Nature was his teacher and the woods of Suffolk his academy; here he would pass in solitude his moments in making a sketch of an antiquated tree, a marshy brook, a few cattle, a sheep herd and his flock, or any other accidental object.”2 Although Gainsborough made more elaborate landscape drawings indoors, tweaking the best elements to suit his composition, he also worked out-of-doors in sketchbooks and on small sheets of paper, considering them exercises.

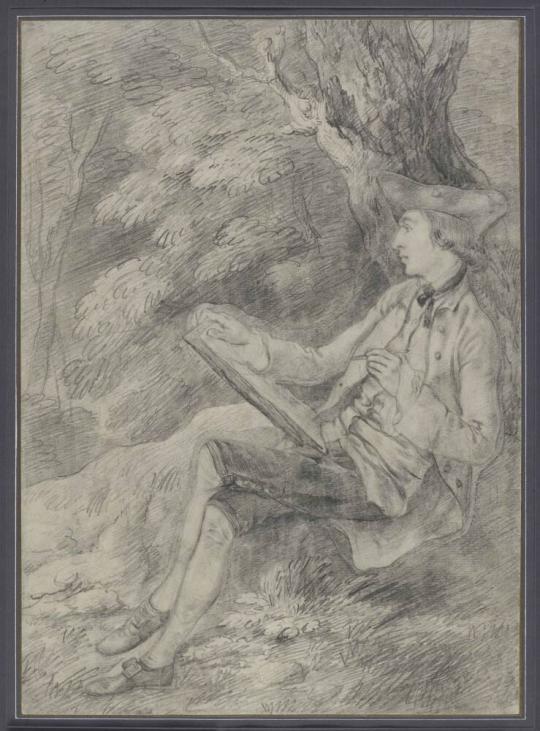

Gainsborough never sold his drawings, keeping most of them or giving them to patrons or friends. This landscape drawing was owned by Joshua Kirby, the theorist, artist, and author of a treatise on perspective with whom Gainsborough was acquainted when living in Ipswich. They remained close friends, ultimately being buried near each other in the graveyard of Saint Anne’s Church at Kew. Kirby’s grandson the Reverend Kirby Trimmer recalled in the 1860s that Gainsborough “gave him [Joshua Kirby] his first drawings” and “above a hundred drawings in pencil and chalk, most of which I still have. . . . so that my family possessed the best collection of his early or Suffolk productions I have seen. There is a full-length self-portrait reclining on a bank, looking at a sketch on a stretching-board, for which he is engaged” (fig. 8.1).3 Gainsborough’s visits with Kirby no doubt influenced him to take inspiration outdoors, where he drew from nature, as well as from previous artists and his own imagination.

Gainsborough used graphite in his early drawings, a medium that he would almost abandon later in his career. He used the pencil to make long, sweeping strokes that indicate movement, and he varied the pressure of the instrument to indicate dark and light passages, suggesting depth. In this sketch, travelers appear toward the center of the composition along a path in the dense woods. The trees are composed of hatching and bent and looped lines, and he has smudged the graphite for further variation. According to John Hayes, “Although much sketchier in treatment, the crisp delineation of the branches, the handling of the foreground, the strongly rhythmical and elongated scallops of the foliage, and the cross-hatching in the sky are closely related to the landscape with peasants and donkey dated 1759 in the Witt Collection” (fig. 8.2).4

Gainsborough was known for depicting figures and animals in dialogue in his works, as seen in this sketch, where a figure rests on the ground close to two others, one positioned on top of a donkey, and the other next to it. The composition evokes the biblical scene of the Flight into Egypt, in which the Virgin Mary and the infant Jesus ride on an ass accompanied by Joseph while fleeing Bethlehem. Yet, in the 1760s, Gainsborough dismissed ever using this subject, commenting that he preferred to “fill up” his compositions with “dirty little subjects of Coal horses & Jack asses and such figures.”5 Gainsborough did have a propensity for observing and then subsequently utilizing the rural poor in his compositions and was known for his charitable nature to the less privileged. Gainsborough would have been familiar with pictorial examples of travelers in fashionable dress with carriages, but in his works, he favored less elevated figures, such as beggars and peasant farmers returning from market, making them appear timeless.6 —Dena M. Woodall

Notes

1. See John T. Hayes, ed., The Letters of Thomas Gainsborough (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2001), 68, no. 40. He wrote to Jackson on June 4 of an unknown year. The term “landskip” was the term most used for landscape from the mid-sixteenth century to the mid-eighteenth century. See Kim Sloan, “A Noble Art”: Amateur Artists and Drawing Masters c. 1600–1800 (London: British Museum Press, 2000), 78.2. The Morning Herald (London), August 8, 1788.

3. Joshua Kirby wrote Dr. Brook Taylor’s Method of Perspective Made Easy, published in Ipswich (1754). He was clearly an early mentor of Gainsborough, and this drawing, among others, was passed through the Kirby family line to his daughter Sarah Trimmer, who was inspired by her father’s observations on nature. Her son, Reverend Kirby Trimmer, commented on the family’s drawings by Gainsborough to Walter Thornbury, see Walter Thornbury, “Turner’s Friends and Contemporaries,” in The Life of J. M. W. Turner: Founded on Letters and Papers Furnished by His Friends and Fellow Academicians (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1862; reprinted 2013), 2:58–59. For more information on Gainsborough’s connection to Joshua Kirby and his theories, see Susan Sloman, Gainsborough’s Landscapes: Themes and Variations (London and Bath: Philip Wilson Publishers and the Holburne Museum, 2012), 14–15.

4. Thomas Gainsborough, Wooded Landscape with Donkeys, Cottage, and Figures Riding on a Path, 1750–55, graphite on laid paper, the Courtauld, London (Samuel Courtauld Trust), Robert Clermont Witt, bequest 1952 [D.1952.RW.2369]. See John Hayes, The Drawings of Thomas Gainsborough (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1971), 1:164, cats. 240 and 238; 2: pls. 73 and 74, respectively.

5. This was in written correspondence between the artist and his friend William Jackson. See Hayes, ed., The Letters of Thomas Gainsborough, 39, no. 22.

6. See Sloman, Gainsborough’s Landscapes, 49–59.

Wooded Landscape with Donkey and Figures

Hayes, John T. The Drawings of Thomas Gainsborough. 2 vols. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1971.

Hayes, John T. “Gainsborough.” Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, 113, no. 5105 (1965): 310–33.

Hayes, John T. Gainsborough Drawings. Washington, DC: International Exhibitions Foundation, 1983.

Hayes, John T. Gainsborough: Paintings and Drawings. London: Phaidon, 1975.

Hayes, John T., and Alan Bowness, Thomas Gainsborough. London: Tate Gallery, 1980.

ProvenanceThe artist; presumably given by the artist to his friend, the artist Joshua Kirby (1716–1784), Kew; his daughter, Sarah Kirby Trimmer (1741–1810), Brentwood, Middlesex; her son, the Rev. Henry Scott Trimmer (1777–1859), Heston, Middlesex; his son, Frederick Edmond Trimmer (1813–1883), Heston, Middlesex; [his sale, Sotheby's, London, December 22, 1883, lot 357 (as one of “five Pencil Sketches by Gainsborough”)]; purchased by Edward Bell (1844–1926), London, 1883-1926; by descent to Mildred Glanville (dates unknown); by whom given to Donald Chisholm Towner (1903–1985), London, 1963–1986; [his estate sale, Sotheby’s London, Eighteenth & Nineteenth Century British Drawings & Watercolours, July 10, 1986, lot 46]; [Davis & Langdale Company, Inc., New York, 1986–1987]; [Jill Newhouse Gallery, New York, by 1996]; purchased by MFAH, 1996.- 04-Exhibition/Display The Audrey Jones Beck Building

Comparative Images

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has made every effort to contact all copyright holders for images and objects reproduced in this online catalogue. If proper acknowledgment has not been made, please contact the Museum.