The These three watercolors—accompanied by an illustrated letter—represent an important addition to John Constable’s oeuvre. The works were made in preparation for an edition of Thomas Gray’s famous and perennially popular poem Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard. The edition was promoted and edited by John Martin, a former bookseller and publisher, who was also secretary of the Artists’ Benevolent Fund, and published by John van Voorst. Martin brought together about fifty prominent artists and wood engravers to illustrate Gray’s poem. The edition required thirty-three illustrations for the thirty-three stanzas, and Martin’s friend John Constable agreed to provide four of the illustrations. A series of preliminary studies for his woodcuts survive, but the finished watercolors were missing. They were discovered in a bound, extra-illustrated copy of the second edition of the printed book that had been retained by Martin and remained with his descendants until 2021.

Constable’s work as an illustrator has been consistently overlooked by scholars. Unlike his great contemporary Joseph Mallord William Turner, who worked continually for publishers, producing illustrations for some of the most celebrated texts of the day, Constable worked on only a handful of projects, and yet they are some of the surest distillations of his approach to landscape. Throughout the 1830s, Constable was increasingly working on graphic projects. He was heavily engaged with his own major print publication, English Landscape Scenery, which appeared in 1830, with a revised edition in 1833, as well as with a series of grand mezzotints made after his most celebrated oils.

By the 1830s, the demand for illustrated editions of popular novels and poems was at its height. John Martin was a bibliographer and bookseller; he had begun his career as assistant to the bookseller Hatchard on Piccadilly before establishing his own firm on Holles Street and later on Bond Street. In 1826 he retired from business and is recorded living on Mount Street, Mayfair, from where he pursued a number of publishing projects, specifically illustrated works. Martin and Constable had known each other well since at least 1828, when Constable agreed to supply him with two paintings. The death of Constable’s wife, Maria, in November 1828 caused Constable to delay in fulfilling this commission. But the two were sufficiently close for Martin to ask Constable to stand as godfather to one of his children.1

In 1830 Martin had already acted as intermediary with Constable over the latter’s involvement in supplying a design for a proposed illustrated edition of Walter Scott’s works, liaising directly with the artist over the engraving of his watercolor of Warwick Castle. Both men agreed at the time that Constable’s work in watercolor was little suited to reproduction in line engraving on steel, Constable noting, “I think with Mr Finden that my poor art is little fitted for line engraving—which I believe is considered the highest style.”2 This statement was slightly disingenuous, as Constable had found the preferred medium for reproducing his own art, mezzotint, and he and Martin evidently spoke regularly about the progress of English Landscape Scenery. Writing to his collaborator on this project, the engraver David Lucas, Constable noted, “Mr Martin told me that our work made some impression at the conversation and many artists said, ‘that was a work they must have.’”3

The first mention in correspondence of Martin’s project to engrave Gray’s Elegy appeared in a letter to the American painter, and his eventual biographer, Charles Robert Leslie. After commenting on the recent death of several close friends, Constable wrote, “Thus am I daily being bereft of some friend or other. To quote a line of that elegy which I am endeavoring to illustrate: ‘The world is left to darkness and to me.’”4

No work could be better suited for Constable to illustrate. Gray’s Elegy had been published in 1751 and was a perennial favorite. It must have particularly appealed to Constable, as it deals with aspects of English village life. The surroundings described by the poet undoubtedly recalled to Constable the quiet churchyard at East Bergholt where he had spent so many happy hours sketching as a youth. As the three watercolors demonstrate, Constable evidently thought long and hard about his choice of subject matter, preparing a series of surprisingly personal and resonant images.

Constable was initially asked to contribute three designs, which were ready and engraved for the first edition of Martin’s book, published by John Van Voorst of Paternoster Row in 1834. These included a vignette of a tower by moonlight, to illustrate Stanza III, “Save that, from yonder ivy-mantled tower”; a view of a church graveyard, seen in early morning light, to illustrate Stanza V, “The breezy call of incense-breathing Morn”; and a vignette of two soldiers contemplating a tomb and its effigy in a church interior, to illustrate Stanza XI, “Can Storied urn, or animated bust.” These three designs have long been known to scholars, as Constable went to a great deal of trouble producing multiple studies and versions of each design in preparation for the finished watercolors.

The first of the watercolors shows a countryman climbing up a path to a moonlit ruin (the “ivy-mantled tower” of the poem). The design is evidently based on Constable’s intense interest in Hadleigh Castle. Constable had visited Hadleigh in 1814, and the ruin greatly impressed him; he revisited the subject for one of the most elegiac and impressive of his six-foot landscapes, completed in 1829 and now at the Yale Center for British Art. The dramatic and romantic potential of Hadleigh continued to appeal to Constable, and it must have been fresh in his mind when Martin commissioned his illustrations. The watercolor recalls Constable’s treatment of Hadleigh for a plate from English Landscape Scenery that was published in 1832. A schematic sketch for the finished watercolor survives in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.5 The watercolor is inscribed on the verso: “John Constable, Novr 6 1833 / For Mr Martin.” This precisely dates the watercolor.

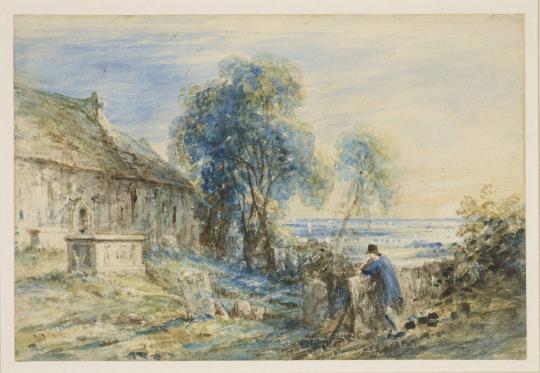

The second watercolor shows a corner of a churchyard with a figure leaning on a tombstone, the scene bathed in early morning light. As Ian Fleming-Williams first noted, the drawing derives from a drawing that Constable made in a small sketchbook he was using in Suffolk in 1813.6 As Graham Reynolds observed, this was typical of Constable’s later work, where topographical studies form the basis for imaginative exploration. The church is reminiscent of St. Mary’s at East Bergholt, a building that had been a constant motif in Constable’s art and life. Constable’s wife, Maria Bicknell, was the granddaughter of the rector of East Bergholt, Dr. Durand Rhudde. Constable had used a view of the East Bergholt church in an earlier publishing project: in 1806 a design by Constable appeared as the frontispiece of A Select Collection of Epitaphs by John Raw of Ipswich. The engraving shows an old man contemplating a tomb which is inscribed “HERE REST . . . / A YOUTH,” an extract from the concluding epitaph of Gray’s Elegy.7 Two preparatory watercolors of the same subject survive in the British Museum; they differ slightly from each other and from the final design.

The third watercolor shows the interior of a church, with two young soldiers—in cadet uniforms—contemplating a medieval tomb, the “storied urn and animated bust” of Gray. This composition, which was known from a preparatory watercolor study, is unusual among Constable’s oeuvre for capturing an interior, theatrically lit. The scene is set in a side chapel, with a medieval monument perhaps loosely based on the monument of John de Montacute in the north aisle of the nave of Salisbury Cathedral. Constable’s decision to place two young cadets at the foot of the medieval tomb may have had an even more personal resonance. Constable’s son, Charles Golding Constable, had recently become a midshipman in the British East India Company’s navy.

Accompanying these three watercolors is a previously unpublished letter written by Constable to Martin on July 9, 1835. The letter discusses an additional design that he had recently been asked to contribute to the second edition of the Elegy. It is apparent from the letter that, at the time of writing, Constable had already supplied Martin with one new image, of Stoke Poges church, which he describes as “with the evening light looking to the West,” and including Gray’s “Cenotaph” in the distance. Stoke Poges church was of particular significance because it was where Gray was buried. This design was eventually chosen by Martin for reproduction on the title page of the second edition, and it is a more accurate rendering of the church than the one Constable had supplied to illustrate Stanza V of the first edition. His original watercolor for this title-page vignette was assumed to be lost until recently identified in the collection of the National Trust, at Anglesey Abbey.

This letter reveals how Constable, ever eager to please, offered to supply an alternative design for Martin, “should you like it better.” This, he wrote, showed the church from the East, thus including Gray’s grave alongside that of the poet’s aunt Mary Antrobus—and Constable supplied a sketch in pen and ink of this alternative design, indicating the approximate positions of the two graves.

Constable’s eagerness to supply designs for Martin suggests that in the 1830s Constable was thinking about the art of illustration. The artists whom Martin had assembled to illustrate Gray’s Elegy represented a considerable quota of the leading landscape painters of the day, including Peter De Wint, Copley Fielding, Richard Westall, William Collins, William Mulready, and George Barret, Jr. In 1834 Martin planned a second venture, a publication of The Seven Ages of Shakespeare. Constable agreed to take on the illustrations of “Jacques and the Wounded Stag” from As You Like It. It was a subject that evidently greatly appealed to Constable. As Martin later observed, “The interest [Constable] took in the trifling affair required of him, is best evinced by the fact that he had made nearly twenty sketches for the ‘melancholy Jaques.’”8 Only nine studies now survive, but they show Constable fascinated by the process of successfully communicating his rich and densely worked design into a book illustration. Constable was working on the same problem with Lucas in preparation for English Landscape Scenery, suggesting that Constable was using his work for Martin to refine his approach to printmaking.

This group of watercolors and illustrated letter represent an important addition to the knowledge of Constable as a graphic artist, working to illustrate a literary text. As with his contribution to The Seven Ages of Shakespeare, Constable’s designs for Gray’s Elegy are a remarkable concentration of artistic effort. His magical evocation of Stanza V, “The breezy call of incense-breathing Morn,” required Constable to produce two fully worked-up watercolor studies before completing the present finished design. The designs represented complex distillations of themes and ideas that he had been working on for a lifetime; as such, they can be viewed as deeply felt works. —Jonny Yarker

Stanza III

Save that, from yonder ivy-mantled tower,

The moping Owl does to the Moon complain

Of such as, wandering near her secret bower,

Molest her ancient solitary reign.

Stanza V

The breezy call of incense-breathing Morn,

The swallow twittering from the straw-built shed,

The cock’s shrill clarion, or the echoing horn,

No more shall rouse them from their lowly bed.

Stanza XI

Can storied urn, or animated bust,

Back to its mansion call the fleeting breath?

Can Honour’s voice provoke the silent dust?

Or Flattery soothe the dull cold ear of Death?

Notes

1. It is unclear which of Martin’s children was Constable’s godchild, but in a letter from Constable to Martin dated February 9, 1832, he notes, “I hop [sic] my little Godchild will not get worse but I shall gladly take the first opportunity of seeing Him.” Leslie Parris, Conal Shields, and Ian Fleming-Williams, eds., John Constable: Further Documents & Correspondence (Westhorpe: Suffolk Records Society, 1975), 166.2. R. B. Beckett, ed., John Constable’s Correspondence, vol. 5 (Westhorpe, UK: Suffolk Records Society, 1967), 88.

3. Ibid., 89.

4. R. B. Beckett, ed., John Constable’s Correspondence, vol. 3 (Westhorpe, UK: Suffolk Records Society, 1965), 105.

5. Graham Reynolds, The Later Paintings and Drawings of John Constable, vol. 1 (New Haven and London: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 1984), 249, cat. 33.15.

6. Ibid., 250, cat. 33.19.

7. Graham Reynolds, The Early Paintings and Drawings of John Constable, vol. 1 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 1996), 73, cat. 6.13.

8. See Ian Fleming-Williams, Constable and His Drawings (London: Philip Wilson Publishers, 1990), 304–5.

Four works by John Constable

Beckett, R. B. ed. John Constable’s Correspondence. Vol. 1. Westhorpe, UK: Suffolk Records Society, 1968.

Hawes, Louis. “Constable’s Hadleigh Castle and British Romantic Ruin Painting.” Art Bulletin 65, no. 3 (September 1983): 455–70.

Parris, Leslie, Ian Fleming-Williams, and Conal Shield. Constable: Paintings, Watercolours, and Drawings. London: Tate Gallery, 1976.

Reynolds, Graham. Catalogue of the Constable Collection. Exh. cat. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1973.

Reynolds, Graham. The Later Paintings and Drawings of John Constable. Vol. 1. New Haven and London: Yale University Press for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 1984.

Reynolds, Graham, Charles Rhyne, and Julius Meier-Graefe. John Constable, R.A. (1776–1837). Exh. cat. New York: Salander-O’Reilly Galleries, 1988.

Reynolds, Graham. The Early Paintings and Drawings of John Constable. 2 vols. New Haven and London: Yale University Press for the Paul Mellon Center for Studies in British Art, 1996.

Smithsonian Institution. Sketches by Constable from the Victoria and Albert Museum. Exh. cat. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1965.

Victoria and Albert Museum. Catalogue of the Constable Collection. London: H.M. Stationery Office, 1973.

ProvenanceThe artist, 1833/35, commissioned by John Martin (1791–1855); John Edward Martin (1822–1893), son of the above; by descent, until 2021; [Lowell Libson & Jonny Yarker Ltd.], 2021–2022; purchased by the MFAH, 2022.Comparative Images

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has made every effort to contact all copyright holders for images and objects reproduced in this online catalogue. If proper acknowledgment has not been made, please contact the Museum.