The affluent Welsh artist Thomas Jones studied at Oxford before attending William Shipley’s School and the St. Martin’s Lane Academy in London for artistic instruction. From 1763 to 1765, he studied in the studio of the fellow Welsh artist and famed landscapist Richard Wilson. Jones joined the Incorporated Society of Artists in 1767 and exhibited there from 1765 to 1780. Following in Wilson’s footpath, Jones traveled to Italy, residing mainly in Rome and then Naples until 1783. The memoirs that he wrote while there provide insight into his thoughts, artistic practice, and the British artists, such as John Robert Cozens, Francis Towne, and John “Warwick” Smith, who were working in Italy at that time.1 When Jones returned to London in 1783, he exhibited his work at the Royal Academy of Arts until 1798 and made drawings for engravings in James Baker’s A Picturesque Guide to the Local Beauties of Wales.2 Jones returned permanently to Wales in 1789, residing in Radnorshire at his family’s estate of Pencerrig, which he inherited from his father.

Jones noted in his memoirs that, by September 1776, he had resolved on “a favourite project that had been in agitation for some Years, and on which my heart was fixed”: his plan to go to Italy.3 Arriving in Rome on November 27, 1776, he recorded his delight of his surroundings within weeks: “New and uncommon Sensations I was filled [with] on my first traversing this beautiful and picturesque Country—Every scene seemed anticipated in some dream—It appeared Magick Land.”4 Jones first saw Rome, its monuments and the Italian landscape, through the lens of his teacher, Richard Wilson, who avoided direct study of the remains of antiquity, preferring to make urban vistas of modern Rome. Jones wrote, “I had copied so many Studies of that great Man, & my Old Master, Richard Wilson, which he had made here . . . that I insensibly became familiarized with Italian Scenes, and enamoured of Italian forms.”5

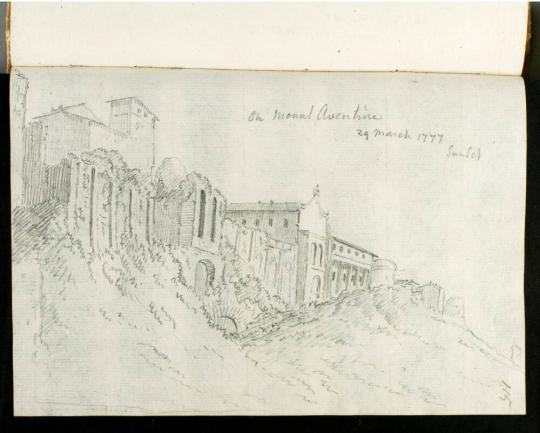

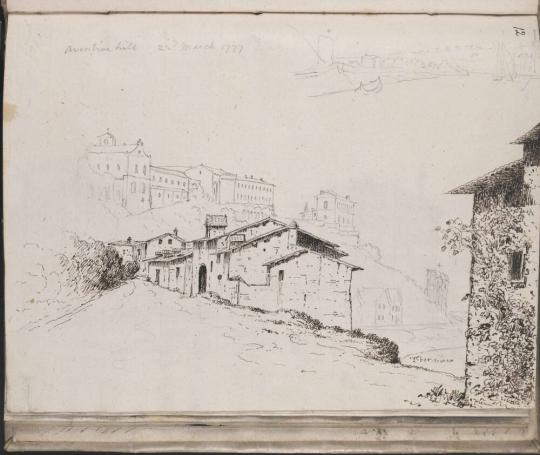

Jones divided his time between the studio, painting commissioned views, and excursions in Rome and its campagna, gathering ideas in sketchbooks to later execute in watercolor and oil. Jones sought out unconventional views of the city. In a pair of sketchbooks, large and small, he meticulously inscribed and dated each sheet, probably retroactively, to accompany on-the-spot sketches.6 Two drawings from Jones’s Large Italian Sketchbook show the ridge of the Aventine Hill from the Strada di Marmorata (figs. 14.1 and 14.2). One records the eastern facade of Santa Sabina, inscribed and dated “on mount Aventine 24 March 1777 sunset.” The other, inscribed “Aventine hill 22nd March 1777,” displays the vista along the Strada di Marmorata with the profile of Santa Sabina and the thin profile of the Villa del Priorato di Malta, along with a quick view across the Tiber toward the Ripa Grande.7

These two studies form the basis for this beautiful watercolor—a grand panoramic vista of the buildings on the Aventine Hill above the Tiber River.8 Mainly relying on the second sketchbook sheet, which he drew from a position near the Ponte Rotto, Jones, drew the principal port, the Ripa Grande, on the right side and left the large block of the Ospizio di San Michele vacant, with only quick dashes of wash; the drawing shows the river’s wide expanse and the sights along the ridge of the Aventine Hill, including the basilicas of Santa Sabina and Santi Bonifacio e Alessio along with the distinctive silhouette of the Villa del Priorato of the Knights of Malta. Jones comes out of the shadow of Wilson with this watercolor, which indicates Jones’s fascination with the geometric potential of the Italian light falling on diverse faces of buildings, successions of rendered planar walls, and terracotta rooftops.9 He leaves the foreground—the street scene on the Strada di Marmorata he depicted in the larger Roman sketchbook—as a reserve, apparently to paint these areas with color later.

Though different from other richly worked watercolors made by him in Rome and at the Castelli Romani in 1777, the precise, lucid wash of this work recalls those of his contemporaries in Italy, such as Francis Towne, and indicates his awareness of the watercolors of Jacob Philipp Hackert and Giovanni Battista Lusieri, who responded to Italy with a frank, contemporary sensibility. This unfinished state offers fascinating insight into Jones’s working practice and the impact of British plein air watercolorists working in Italy in the 1770s and 1780s. Its bold treatment of the urban landscape of Rome also connects to Jones’s later intimate, yet progressive, oil sketches of the stark geometry and textured surfaces of Naples in midsummer, for which he is exalted. —Dena M. Woodall

Notes

1. See Thomas Jones and Adolf Paul Oppé, “Memoirs of Thomas Jones,” Walpole Society, 32 (1946–48): 1–172. Printed for the Walpole Society by Oliver Burridge, London, 1951.

2. See James Baker, A Picturesque Guide to the Local Beauties of Wales (London: W. Justins, 1791; Worcester: J. Tymbs, 1795).

3. See Jones and Oppé, “Memoirs of Thomas Jones,” 37.

4. Ibid., 55.

5. Ibid.

6. For the Small Sketchbook, 1776–77, graphite, pen and ink, and watercolor on Italian laid writing paper, British Museum, London [1981-5-16-17].

7. For the sketches, see Large Sketchbook, Showing “On Mount Aventine” and “Aventine Hill,” graphite; graphite, pen, and brown ink on Italian laid writing paper, British Museum, London [1981-5-16-18]. Thanks to Jonny Yarker and Hugo Chapman, the Simon Sainsbury Keeper of Prints and Drawings, British Museum, for showing me this sketchbook in March 2023.

8. This watercolor has been dated to the 1780s and was most likely made in Rome. See Ann Sumner, Greg Smith, and Christopher Riopelle, Thomas Jones (1742–1803): An Artist Rediscovered (New Haven: Yale University Press, in association with National Museums and Galleries of Wales, Cardiff, 2003), 199, cat. 91. The watermark on the sheet confirms this dating. A Jacob Philipp Hackert drawing in the Morgan Library and Museum has the same watermark. See Study of a Tree, 1790s, pen and brown ink over graphite on paper, Morgan Library and Museum, Thaw Collection [2017.119]. For Jones’s use of paper, see Peter Bower, “Careful and Considered Choice: Thomas Jones’s Use of Paper,” in Thomas Jones (1742–1803): An Artist Rediscovered, 101–7.

9. See ibid., 53.

The Aventine from the River Tiber, Rome

Conisbee, Philip. Painting from Nature: The Tradition of Open-Air Oil Sketching from the 17th to 19th Centuries. Cambridge: Fitzwilliam Museum; London: Royal Academy of Arts, London; Arts Council of Great Britain, 1980.

Egerton, Judy. “Thomas Jones. Cardiff and Manchester.” Burlington Magazine 145, no. 1205 (August 2003): 598–99.

Gowing, Lawrence. The Originality of Thomas Jones. London: Thames and Hudson, 1985.

Hawcraft, Francis W. Travels in Italy 1776–1783: Based on the Memoirs of Thomas Jones. Manchester: Whitworth Art Gallery, 1988.

Jones, Thomas, and Adolf Paul Oppé. “Memoirs of Thomas Jones.” Walpole Society 32 (1946–48): 172. London: Printed for the Walpole Society by Oliver Burridge, 1951.

Rosenthal, Michael. “Thomas Jones.” Grove Art Online, 2003, https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T045115.

Sumner, Ann, Greg Smith, and Christopher Riopelle. Thomas Jones (1742–1803): An Artist Rediscovered. New Haven: Yale University Press, in association with National Museums and Galleries of Wales, Cardiff, 2003.

Provenance[Thomas Agnew & Sons, London, 1959]; purchased by Walter Augustus Brandt (1902–1978), 1959–1978; by descent, 1978–2022; [Lowell Libson & Jonny Yarker, London, 2022–2024]; purchased by MFAH, 2024.- (not entered) The Audrey Jones Beck Building

Comparative Images

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has made every effort to contact all copyright holders for images and objects reproduced in this online catalogue. If proper acknowledgment has not been made, please contact the Museum.