Amelia Noel was a Jewish artist whose father, Judah Levy, was an American merchant of Heydon Square, Minories. In 1781 she married a Jew called Zebe or Zvi Noah, known as Henry Noel, in the synagogue in Duke’s Place, London.1 His bankruptcy is recorded in 1783, and it appears that he abandoned her and took her money. Between 1795 and 1804, Noel exhibited landscapes, historical subjects, and other undescribed drawings (most likely watercolors) at the Royal Academy of Arts. Joseph Farington records in his diary that she had excellent networking abilities and personal charm. She visited him with her daughter Frances on April 8, 1804, to garner his support of her work’s acceptance into the Royal Academy that year; Faring describes Noel stating that

“it was of great consequence to Her to have a picture in the Exhibition as Her Scholars judged of Her ability in the Art from that circumstance. . . . She sd. She supported a family of 4 Children giving lessons in painting & drawing.” She also mentioned to him that Benjamin West and Richard Cosway were her friends, underscoring her artistic milieu.2 Noel’s drawing lessons extended to royalty, as she was the drawing mistress to the daughters of George III. The artist advertised instruction to ladies in “drawing & painting (in oil water colours and crayons) landscape, figures, cattle, flowers, transparencies &c, at two guineas for twelve monthly lessons.”3 Noel, along with her daughter Frances, also gave instruction in painting on velvet. In John Fetham’s The Picture of London for 1804, he commented on her skill: “The elegant and scientific works of this lady for her superior talent and genius, are patronized by the royal family, nobility &c.”4 Noel’s artistic abilities extended to being an astute engraver and publisher, which was extremely rare for a woman during this time. In 1797 she showed Six Views in the Isle of Thanet at the Royal Academy and published her acclaimed series of topographical etchings Views of Kent, which was dedicated to Princess Charlotte.5 On May 18, 1798, after a disastrous fire at her residence, the Times noted her artistic ability and her royal patronage: “We . . . hope this promising Artist will be reinstated in a situation to enable her to exercise her pencil for the gratification of the Public, who can never fail to encourage the exertions of an English female, who has cultivated her genius and employed her talents in the charming art of Drawing and Painting.”6

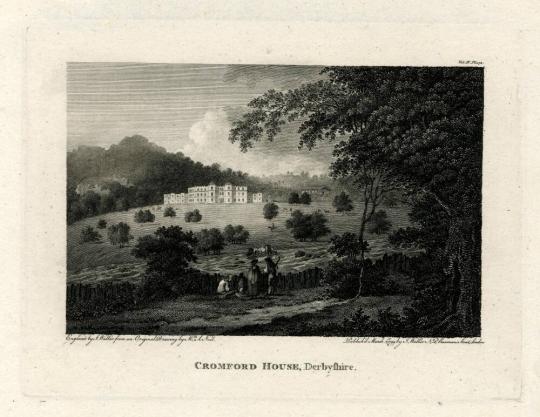

Two of Noel’s watercolors, including this one of Willersley Castle and the prominent tourist location Lake Windermere in the Lake District, were reproduced as engravings in volume four of The Copper-Plate Magazine (fig. 20.1), also called Elegant Cabinet of Picturesque Prints, Consisting of Sublime and Elegant Views in Great Britain and Ireland, which was a five-volume set with 250 copperplate engravings, providing a noteworthy survey of urban and rural locations and country houses and encouraging middle-class audiences to become virtual tourists to estates they might never visit.7 The magazine included imagery from a host of artists, amateur and professional alike, including Paul Sandby and Thomas Girtin.

Noel’s watercolor, on which the engraving is based, is the earliest dated view of the mansion house of Willersley Castle of the industrialist Sir Richard Arkwright (1732–1792). Her skillful delineation of each element translated well to engraving. Noel pictures Willersley Castle resting on a rocky outcropping looking upon the town of Cromford and the valley of the Derwent River in the lush Derbyshire Dales. Its location was remarked upon for “the eminence of the house . . . can only be appreciated to full advantage by mountain climbers willing to ascend the limestone crags on the south edge of the park.”8 John Byng, in his 1789 tour of the area, acerbically commented, “He [Sir Richard Arkwright] has made a happy choice of ground, for by sticking it up on an uneven bank, he contrives to overlook, not see, the beauties of the river, and the surrounding scenery.”9 The watercolor includes in the distant right the building that housed the coach house and stables, designed by Thomas Gardner. Figures, seemingly tourists, in the foreground appear to be taking a rest before journeying upward to the mansion. The principle entrance to the estate is beside the medieval river bridge, unseen to the right.

Arkwright had commissioned Willersley Castle in 1786, the year he was knighted by King George III, and in the subsequent year he was made High Sheriff of Derbyshire.10 Arkwright became a central figure in the Industrial Revolution and supported the invention of the water-powered cotton mill and created the world’s first factories.11 Upon his death in 1792, the Gentleman’s Magazine recorded that “he died immensely rich, as he has left manufactories the income of which is greater than that of most German principalities.”12

Willersley Castle, designed by the London architect William Thomas and built in 1782–88, is in the Neoclassical manner called the “Robert Adam Castle style,” described as robust on the exterior with a delicate and restrained classical interior. John Webb designed the grounds, meant for pleasure, turning the meadows sloping down to the Derwent River into an arcadian park with a private chapel. Noel depicted it before its completion in 1791. Willersley Castle was portrayed by other artists at that time, for Arkwright was an important patron of Joseph Wright of Derby, who made a portrait of the industrialist and of his children and grandchildren as well as views of his industrial empire, including pendants in oil of his 1771 mill at Cromford and his estate of Willersley Castle (fig. 20.2).13 A later engraving of the mansion was published by Henry Moore in his Picturesque Excursions from Derby, in which he observed, “In front the ground forms a fine extent of lawn, but it is too much spotted with trees, which gives it the appearance of an orchard; and thus spoils a fine appendage to an elegant mansion.”14 From the castle, Arkwright’s view of the Cromford mills and the town on the other side of the river was blocked by the high feature of an immense limestone rock, called Scarthin Nick, suggesting “his graduation from industrialist to country gentleman.”15 —Dena M. Woodall

Notes

1. See Stephen Massil, “The Lady of Longuieville Clarke,” Jewish Historical Studies, 42 (2009): 53–73.

2. See Joseph Farington, Kenneth Garlick, and Angus Macintyre, eds., The Diary of Joseph Farington, vol. 6, April 1803—December 1804 (London: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art; New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979), 2,293.

3. See the Times, October 19, 1799.

4. See John Fetham, The Picture of London for 1804 (London: Richard Phillips, 1804), 260, and Neil Jeffares, “Noel, Amelia, Mrs Henry, née Minka Levy,” in Dictionary of Pastellists before 1800, online edition, http://www.pastellists.com/Articles/NoelA.pdf.

5. See David Alexander, Caroline Watson and Female Printmaking in Late Georgian England (Cambridge: Fitzwilliam Museum, 2015), 71.

6. It was written in the Times, May 18, 1798. See David Alexander, “Noel, Amelia,” in A Biographical Dictionary of British and Irish Engravers 1714–1820 (New Haven and London: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2021), 654.

7. See The Copper-Plate Magazine, or Monthly Cabinet of Picturesque Prints: Consisting of Sublime and Interesting Views in Great Britain and Ireland, Beautifully Engraved by the Most Eminent Artists from the Paintings and Drawings of the First Masters, vols. 1–5, specifically vol. 4 (London: J. Walker & H. D. Symonds, 1792–1802). See also Tim Clayton, “Publishing Houses: Prints of Country Seats,” in The Georgian Country House: Architecture, Landscape and Society, ed. Dana Arnold Stroud (Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing, 1998), 43–60, esp. 56. The other watercolor and engraving by Amelia Noel is Windermere, 1795–1804, watercolor, British Museum, London [1890,0512.124]. T. Tagg, after Amelia Noel, Windermere, Westmoreland, for the series The Copper-Plate Magazine, vol. 4 (1798), pl. 155, British Museum, London [1890,0512.125]. The Windermere watercolor was also purchased through Christie’s from Dr. John Percy’s sale on April 22, 1890, like Willersley Castle. See also John Murdoch, ed., “The English Lake District,” in The Discovery of the Lake District: A Northern Arcadia and Its Uses (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1984), esp. 29, cat. 44 (as Amelia Nowell, Windermere and Belle Isle, watercolor).

8. See Barry Joyce and Doreen Buxton, “Willersley Castle, Cromford” (research paper, Derwent Valley Mills World Heritage, 2011).

9. See John Byng Torrington (5th Viscount), John Beresford, and Cyril Bruyn Andrews, eds., The Torrington Diaries Containing the Tours through England and Wales of the Hon. John Byng (Later Fifth Viscount Torrington) between the Years 1781 and 1794, vol. 2 (New York: H. Holt, 1935, 40, entry of June 14, 1789.

10. Since 1776, Arkwright had lived at Rock House, also in Cromford.

11. See R. Fitton, The Arkwrights, Spinners of Fortune (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1990), and Benedict Nicolson, Joseph Wright of Derby: Painter of Light (London: Routledge/Kegan Paul, the Paul Mellon Foundation for British Art, 1968), 164–66.

12. See the Gentleman’s Magazine 62, no. 2 (1792): 770–71. Willersley Castle remained with his family, by descent, until it became an auxiliary hospital during World War I.

13. See Joseph Wright of Derby, Willersley Castle, Cromford, 1783, oil on canvas, formerly Colonel M. H. Grant collection. See London, Christie’s, Revolution, April 13, 2016, lot 7; Nicolson, Joseph Wright of Derby, 2:265, cats. 312–13, pls. 330–31; and Judy Egerton, Joseph Wright of Derby 1734–1797, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1990), 200, under cat. 127. A drawing by George Robertson (1748–1788) is known and was probably produced when Robertson worked for William Duesbury at the Derby China Manufactory. It shows how John Webb’s landscape designs were implemented with grassland that sweeps down to the River Derwent. See George Robertson, Willersley Castle and Park, probably late 1790s, pen and ink on paper, location unknown.

14. After Henry Moore, published by William G. & George Crooke, Willersley Castle. Seat of Richard Arkwright Esq. Derbyshire, for The Beauties of England and Wales, 1804, engraving. See Henry Moore, Picturesque Excursions from Derby to Matlock, Bath and Its Vicinity; Being a Descriptive Guide to the Most Interesting Scenery and Curiosities in that Romantic District, With Observations Thereon, published by Henry Moore, drawing master, printed by T. Wilkinson, Ridgefield, Manchester, 1818.

15. See Nicolson, Joseph Wright of Derby, 167. A year later, it was damaged by a fire; Arkwright’s children and grandchildren would have enjoyed it longer than he did.

The Seat of Richard Arkwright, Cromford, near Matlock

Alexander, David. Caroline Watson and Female Printmaking in Late Georgian England. Cambridge: Fitzwilliam Museum, 2015.

Clayton, Tim. “Publishing Houses: Prints of Country Seats.” In The Georgian Country House: Architecture, Landscape and Society. Edited by Dana Arnold. Stroud, UK: Sutton, 2003.

Egerton, Judy. Joseph Wright of Derby, 1734–1797. Exh. cat. Paris: Reunion des Musees Nationaux, 1990.

Farington, Joseph, Kenneth Garlick, and Angus Macintyre, eds. The Diary of Joseph Farington. Vol. 6, April 1803–December 1804. London: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art; New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979.

Fitton, R. The Arkwrights, Spinners of Forture. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Gainsborough’s House. Home and Abroad: Drawings and Watercolours from a Private Collection 1700 to 1840. Exh. cat. Sudbury, UK: Gainsborough House, 2012.

Jeffares, Neil. “Noel, Amelia, Mrs Henry, née Minka Levy.” In Dictionary of Pastellists before 1800, online edition. http://www.pastellists.com/Articles/NoelA.pdf

Massil, Stephen. “The Lady of Longueville Clarke.” Jewish Historical Studies 42 (2009): 53–73.

Murdoch, John, ed. “The English Lake District.” In The Discovery of the Lake District: A Northern Arcadia and Its Uses. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1984.

Nicolson, Benedict. Joseph Wright of Derby: Painter of Light. London: Routledge/Kegan Paul, The Paul Mellon Foundation for British Art, 1968.

ProvenanceThe artist, by 1798; Dr. John Percy (1817-1889) (Lugt 1504), London, by 1876; [London, Christie’s, Catalogue of the very valuable and extensive collection of Water-colour Drawings of D. John Percy, F.R.S., 22 April, 1890, lot 897]; Walter Augustus Brandt (1902-1978), at least by 2012-2022; by descent, 1978-2022; [Lowell Libson and Jonny Yarker, Ltd, London, 2022-2023]; given to the MFAH, 2023.1 John Percy was a Fellow of the Royal Society and member of the Burlington Fine Arts Club. According to Sidney Colvin, the 19th-century keeper of prints and drawings at the British Museum, his collection was “the most complete ever formed for the illustration of the history of British art, especially English watercolour painting.” [Fig 9].

2 Walter Brandt (1902-1978) Brandt was a pioneering collector of neoclassical and romantic drawings who formed his collection in the decades after WWII. He was also the brother of the acclaimed photographer Bill Brandt. Brandt, the son of Ludwig and Lili, was born in Hamburg in 1902. The family came to London in the 1920s, and in 1923 Walter entered the family firm of William Brandt & Son & Co., an international trading agency based in the City. It was during the second world war, his wife and children living in Cornwall, that Walter began collecting. His first interest was modern British art, and he purchased works by artists including John Piper and Henry Moore. However, his collecting habits moved on to focus on works by British artists born before 1800, a criteria he stuck to fairly rigorously, with a few slight exceptions. Brandt was unusual amongst watercolor collectors of the time in that he never bought bundles of drawings, and so each individual sheet in the collection was specifically chosen, resulting in a collection of unusual and remarkable quality. (See Sudbury, Gainsborough’s House, Home and Abroad: Drawings and Watercolours from a Private Collection 1700 to 1840, exh. cat. June 30-September 29, 2012 and London, Christies, British Drawings and Watercolors, 7 June 2023, under lot 113). [Fig 10].

- (not entered) The Audrey Jones Beck Building

Comparative Images

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has made every effort to contact all copyright holders for images and objects reproduced in this online catalogue. If proper acknowledgment has not been made, please contact the Museum.