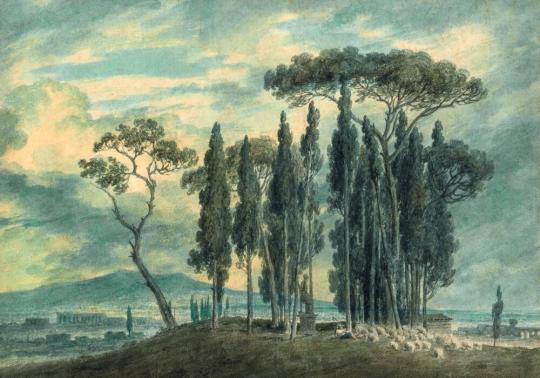

Monte Della Giustizia, Villa Montalto - Negroni, Rome

Constable, William George. Richard Wilson. London: Routledge Kegan Paul, 1953.

Farington, Joseph. The Diary of Joseph Farington. Vol. 7, January 1805–June 1806. Edited by Kathryn Cave. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1982.

Ford, Brinsley. The Drawings of Richard Wilson. London: Faber and Faber, 1951.

Postle, Martin, and Robin Simon. Richard Wilson and the Transformation of European Landscape Painting. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014.

Solkin, David H. Richard Wilson: The Landscape of Reaction. London: Tate Gallery Publications, 1982.

ProvenanceWilliam Lock of Norbury (1732–1810), acquired from the artist; [probably Lock sale, Sotheby’s, London, A Catalogue of the Valuable Collection of Prints and Drawings of the later W. Lock, Esq. removed from his late Residence, Norbury Park, Surry, consisting of Prints . . . Capital Drawings . . . And a Numerous Assemblage of the Works of R. Wilson, R.A. . . ., May 3, 1821, part of lot 377 (as “Ditto, Villa Negroni, &c”)]; presumably purchased at the above sale, Richard Ford (1796–1858); by descent, Captain Richard Ford (1860–1950); [his sale, Christie’s, London, Catalogue of the Collection of Pictures by Richard Wilson, R.A. the Property of Captain Richard Ford…,June 14, 1929, lot 24]; [Sotheby’s, London, Fine Eighteenth, and Nineteenth Century English Drawings and Watercolours, April 5, 1973, lot 43]; [Colnaghi, London, November 1973]; Professor Eric Stanley, Oxford (1923-2018); [Christie’s, London, Old Master and British Drawings & Watercolours, July 2, 2019, lot 200]; [Lowell Libson & Jonny Yarker Ltd, London, 2019-2021]; purchased by MFAH, 2021.- (not entered) The Audrey Jones Beck Building

The years that Richard Wilson spent in Italy during the 1750s marked a turning point in his professional career and for the trajectory of European landscape art, as witnessed by the pioneering works of art that he produced at this time, of which the present drawing is an early example. Before his departure for Italy in 1750 in his mid-thirties, Wilson gave little indication that he was anything more than a competent society portrait painter, with a sideline in landscapes derived from the traditions established by seventeenth-century Dutch and Italian masters. He first began to turn his attention seriously toward landscape while in Venice in 1751, encouraged by the Italian painter Francesco Zucarelli. William Lock, who journeyed with him from Venice to Rome, and who acquired the present drawing from him, reminisced many years later that Wilson was, at the time, “fluctuating whether to pursue portrait or Landscape,” but that, “Vernet by warmly approving his Landscapes decided him to follow that branch of art.”1 Claude-Joseph Vernet, an influential French academic painter, then resident in Rome, certainly played a part in persuading Wilson to forsake portraiture for landscape. However, the ultimate reason why Wilson embraced landscape was Italy itself, and the experience of drawing and painting at firsthand from nature, which was in turn the key to his seminal contribution to the transformation of the genre. The acquisition of the present drawing by William Lock, as well as his companionship with Wilson in Italy, was also of considerable significance.

William Lock (1732–1810) traveled with Wilson and another friend, Thomas Jenkins, from Venice to Rome in the winter of 1751, the three men traveling together in Lock’s carriage. Lock, who was then age eighteen, and who at that time apparently went by the name of William Wood, was the natural son of William Lock, a London merchant and Member of Parliament. An established connoisseur and collector of Old Master paintings, Lock provided his son with the means to travel to Italy, and the younger Lock later inherited his fortune.2 Clearly, Wilson’s relationship with Lock took the form of mentor and friend, which explains also why Lock acquired so many of Wilson’s Italian sketches, as well as a number of finished oil paintings and his own portrait (now untraced).3 In later life, Lock, who took up residence at Norbury Park, Surrey, was also to become an important collector of Old Master paintings in his own right, including an iconic work by Claude Lorrain, Seaport with the Embarkation of St Ursula, now in the National Gallery, London. Named in 1787 by Sir William Hamilton as one of the three “true Connoisseurs of the arts in England,” Lock was also in later life an important voice in the critical acceptance of Wilson as one of the founders of the British School.4

The present artwork, which may well have been made in the presence of Lock, has all the qualities of a sketch made on the spot, en plein air. The materials, black chalk heightened with white on blue-gray colored paper, are characteristic of Wilson’s practice at the time. The composition is executed in rapid strokes using a porte-crayon, a double-ended metal tube split at both ends, allowing chalk to be inserted at both ends, in this instance black and white. The technique was without doubt influenced by the French artists Wilson had encountered at the Académie de France à Rome, including Vernet and Gabriel-Louis Blanchet, whom he accompanied on sketching expeditions. Typically, Wilson sketched with great economy; here, he established a nuanced tonal range in order to capture the transient elements as well as the essential topography, the scudding clouds indicated by the lightest of touches against an otherwise clear sky. The composition is anchored by the central group of cypress trees and umbrella pines, together with a classical statue of seated Roma and an adjacent villa structure. The site of the statue of Roma, at the highest point of the hill and accessed by a flight of steps, was known popularly as the Monte di Giustizia due to the misconception that the statue featured a figure of Justice. A human presence is provided by the three figures in the midground, possibly workers on the estate. The effect is both immediate and timeless, a personal evocation of a historic setting.

As Wilson’s inscription confirms, the location is the Villa Negroni, at that time one of the most significant historic villas in Rome, its estate extending across parts of the Viminal, Quirinal, and Esquiline hills. The villa had been established in the 1570s by Cardinal Felice Peretti on the site of vineyards that he had recently purchased. Designed by the architect Domenico Fontana, it was completed by 1581. Four years later, in 1585, Peretti was elected Pope, taking the name of Sixtus V, at which time he passed the property, known as the Villa Montalto Peretti, to his sister. As well as the villa complex itself, the estate comprised extensive gardens designed also by Fontana, with terraces, statuary, and fountains, offering views across the Eternal City. Subsequently, the villa began to fall into disrepair, and was sold to the Negroni family in 1696. In the decades following Wilson’s visit, the villa gained renewed celebrity owing to excavations carried out in 1777, which uncovered a magnificent Roman house decorated with well-preserved ancient frescoes. They formed the basis for a plein air oil sketch by Wilson’s former pupil, Thomas Jones (fig. 4.1), whose traveling companion, the artist-turned-dealer Henry Tresham, purchased it for the Earl of Bristol.5 The Villa Negroni remained in the family’s possession until 1784, when it was acquired by the merchant Giuseppe Staderini, who immediately set about recouping his investment by stripping it of the various works of art. The villa and gardens survived until the 1860s, when, due to the construction of Termini, Rome’s principal railway station, they were destroyed piecemeal. Today, only one fountain survives, the Fontana del Prigione, situated in via Goffredo Mameli on the slopes of the Janiculum Hill.

Wilson was not the first artist to portray the gardens of the Villa Negroni, although earlier images had generally taken the form of published prints showing bird’s-eye views of the villa and its formal gardens or focused depictions of its elaborate Baroque fountains.6 In later decades of the eighteenth century, other artists were also attracted to the gardens, including Richard Cooper (1714–1814), whose View Taken in the Gardens of the Villa Negroni at Rome was published as an aquatint by Boydell about 1778–79. Although Cooper’s composition is relatively formal, and taken from a slightly different angle to Wilson’s, it also includes the classical statue of Roma, cypresses, and umbrella pines, as well as a building that may equate to the one in Wilson’s sketch. While Cooper’s view is reversed in the print, a comparison between the original drawing (fig. 4.2) and Wilson’s sketch reveals the compositional affinities.7 Closer in spirit to Wilson’s sketch is a watercolor by John Robert Cozens, made probably on a visit to the gardens of the Villa Negroni in January 1783, on his second trip to Italy, when he accompanied the young William Beckford (fig. 4.3).8 Like Wilson, whom he revered, Cozens bypassed the formal elements of the garden to concentrate instead upon its potential as an evocation of the spirit of the place and its locus as a landscape of memory. —Martin Postle

Notes

1. Joseph Farington, The Diary of Joseph Farington, vol. 7, January 1805–June 1806, ed. Kathryn Cave (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1982), 2597 (28 July 1805).2. In his will dated 1755, William Lock made his will in favor of “William Lock of Cavendish Square, now residing with Mary Wood, but who from his birth till very lately was called and known by the name of Wood.” A. F. Twist, Widening Circles in Finance, Philanthropy and the Arts: A Study of the Life of John Julius Angerstein 1735–1823 (Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam, 2002), 11.

3. For the sale of Lock’s collection of works by Wilson, see A Catalogue of the Valuable Collection of Prints and Drawings of the Later W. Lock, Esq. Removed from His Late Residence, Norbury Park, Surry, Consisting of Prints . . . Capital Drawings . . . And a Numerous Assemblage of the Works of R. Wilson, R.A. . . . , Sotheby’s, May 3, 1821. Among the Italian oil paintings owned by Lock is Lake Nemi and Genzano from the Terrace of the Capuchin Monastery, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 05.32.3.

4. John Ingamells, A Dictionary of British and Irish Travellers in Italy 1701–1800 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1997), 608.

5. Thomas Jones, An Excavation of an Antique Building in a Cava in the Villa Negroni, Rome, Tate, T03544. See also Hetty Joyce, “The Ancient Frescoes from the Villa Negroni and Their Influence in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries,” Art Bulletin 65, no. 3 (September 1983): 423–40.

6. See for example, “Giardino del Ill.mo Card. Montalto,” published by Giovanni Domenico de’ Rossi, 1623, British Museum, 1972 [U.184.26]; Giovanni Francesco Venturini, “Fontana Nel Giardino Montalto,” 1691, Hamburger Kunsthalle [kb-1952-234-16].

7. The original drawing upon which the print is based is in the National Galleries of Scotland [D 981]. See Christopher Baker, “Richard Cooper in Rome,” British Art Journal 5, no. 3 (Winter 2004): 37–40.

8. John Robert Cozens, In the Gardens of the Villa Negroni at Rome, graphite and watercolor with scratching out, 10 1/4 x 14 5/8 in. (26 x 37.2 cm), Christie’s, London, 6 July 2021, lot 99.

Comparative Images

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has made every effort to contact all copyright holders for images and objects reproduced in this online catalogue. If proper acknowledgment has not been made, please contact the Museum.