The young Joseph Mallord William Turner painted this powerful depiction of Bridgnorth in the second half of the 1790s, when he was still establishing his reputation in the London art world. Between 1792 and 1799, he regularly left the British capital to explore the picturesque and sublime sites of Wales on successive summer tours. Turner’s journey to Wales in 1794 concentrated on its northeast, and on the towns and countryside of the neighboring English Midlands.1 This was an area steadily undergoing transformation as a result of industrialization, especially in Birmingham and surrounding towns. Turner’s subject here, Bridgnorth (in the English county of Shropshire), lies on the River Severn just a few miles downriver from Ironbridge and Coalbrookdale, which were collectively an epicenter of the new intensive industrial processes.

In drawing up his itinerary in advance of the journey, the nineteen-year-old artist made no reference to those contested places as being of potential interest but instead very purposefully tailored his route to encompass a number of cathedral or market towns, including Bridgnorth, that he had been commissioned to depict, and which were subsequently engraved for John Walker’s Copper-Plate Magazine.2 Drawing on information from others, Turner noted that Bridgnorth had “a remarkable Tower on a steep rock, an upper & lower town with step for Foot Passengers. Bridge with 7 arches and a gatehouse.”3

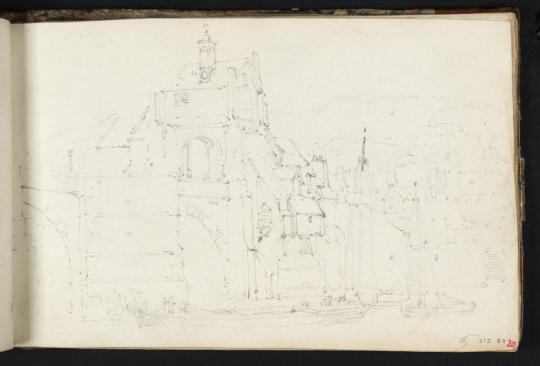

Turner’s tour sketchbook includes just two sketches at Bridgnorth, and as with many other artists (both before and after), the stone bridge was the feature that preoccupied him (fig. 29.1).4 It effectively spanned the Severn in two stages. On the west side were five large arches, resting on sturdy prow-shaped piers (or bulwarks). Beyond them were two smaller arches that carried the road to the east bank. On the pier where the two types of arches met there was an ancient gateway, topped by a small room with a bell tower (possibly a chapel dedicated to St. Osyth). The gateway was flanked on its southern side by a ramshackle wooden tollhouse with assorted gables and chimneys. From this part of the bridge, it was possible to get onto a spit of land, accessible when the river was not in full flood, linking it to an island known as the Bylet.

A view looking up to the bridge from the northern tip of the island was recorded by Thomas Girtin (1775–1802), Turner’s friend and frequent collaborator in the years between 1794 and 1798.5 Another depiction of Bridgnorth (fig. 29.2), facing more or less in the opposite direction from the viewpoint of that bridge scene, is now in the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens at San Marino, California, and has also been attributed to Girtin, though Greg Smith has qualified this attribution recently in the entry for his online catalogue raisonné.6 It is readily apparent that the little Huntington study records the same composition as the present watercolor by Turner. It appears to have been part of a batch of about sixty works painted on small cards, mostly by Girtin (derived from designs by other artists), for Dr. Thomas Monro in the 1790s. Many of these were later acquired by Turner at Dr. Monro’s posthumous sale in 1833, but it is not known whether the Bridgnorth subject was among them.

Since no sketch for Bridgnorth on the River Severn has been traced among those Turner made in 1794, and there is no solid evidence of other visits to Bridgnorth until the 1830s,7 this smaller version poses tantalizing questions that have a bearing on the dating of both items. Was it the source for the Turner image? Did Girtin (or whoever) paint it on the spot, or was it based on another artist’s drawing? Alternatively, could the small version of the Bridgnorth subject perhaps be just a record of Turner’s watercolor by Girtin or one of the other artists who attended Dr. Monro’s informal academy?

Close comparison of the two works reveals some details that would have been difficult for Turner to have embellished with any degree of accuracy if this small watercolor was his source material, most conspicuously the architecture, which is barely resolved in the Huntington version. At the center of both images is the tower of Thomas Telford’s church of St. Mary Magdalene, on which work began in 1792 and would still have been underway at the time of Turner’s visit in 1794; the church was eventually consecrated on July 22, 1796.8 In reality, the building is situated much closer to the Severn Bridge, whereas Turner opens out and deepens the space by deploying the meandering curve of the river and above it the sharply rising ground on which the upper town is constructed. This pushes the church farther into the distance, simultaneously providing the opportunity to create its tranquil reflection. The bell tower is in fact rather more elongated and is positioned at the center of the church’s north facade; but the first impression here is that it sits behind it. However, the eye-catching pediment may actually be intended to represent another building on the slope below the church. To its left is the vertical stump of the remaining ruins of the town’s castle.

Turner sometimes misremembered details he had studied on the spot when working up his pencil sketches back in his London studio, so the discrepancies noted above might suggest that (assuming he was working from one of his own sketches) a period of time had elapsed. Alternatively, he could have been working from another artist’s outline sketch, blindly following the compressions they made in composing the scene. Another curious feature is the rocky bluff that frames the right side of the image. Its tapering shape recalls the massive bulwarks of the bridge’s piers. Perhaps this was a detail Turner chose to misread in working from his original source, opting instead for the kind of wild and enclosed valleys favored by Salvator Rosa.

Stylistically, the watercolor seems more ambitious in scale and accomplished in its re-creation of nuanced atmospheric effects than anything Turner produced in the immediate aftermath of the 1794 tour, but it is unlikely it was painted as late as 1802, as the inscription on the mount proposes. The connection with the “Girtin” version of the scene tends to support the notion that it was more likely painted during the mid-1790s, when both artists were working for Dr. Monro. Furthermore, Turner was making use of the sketches he had gathered in 1794 for at least one of his exhibits at the Royal Academy in 1796: a view of the market fair at Wolverhampton, about twenty miles from Bridgnorth.9 Another watercolor created about that year, showing the ruins of Buildwas Abbey (Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester), was based on a now untraced pencil outline that formerly belonged to Charles Stokes, one of Turner’s friends in later life, and is another subject sketched in the near vicinity of Bridgnorth in 1794.10 In addition to the topographical resonances of these watercolors, they also share much the same dimensions as those of the present work.11

It is also possible to find correspondences in some of the incidental details in these works. For example, the lean and somewhat compact figures making their way across the sandy paths of the island in Bridgnorth on the River Severn find counterparts in the distant crowd in the Wolverhampton scene. Sunlight illuminates the facades of the houses in that work in much the same way it illuminates the pedimented building at the center of Bridgnorth on the River Severn. Another watercolor that Turner exhibited in 1796 shows the decayed bridge and its unbroken reflection at Llandeilo (National Museum Wales), as well as cottages that share similarities with the terraced houses in Bridgnorth on the River Severn.12

Perhaps the most memorable aspect of this watercolor is Turner’s skilful treatment of the sky, with the threat of an imminent storm, as heavy dark clouds roll in from the southwest. During the next few years, Turner would make such effects the essence of his art, so that they sometimes overwhelmed the topographical element. However, here both constituents are held in balance, each contributing to the strength of the image. —Ian Warrell

Notes

1. See Eric Shanes, Young Turner: The First Forty Years, 1775–1815 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2016), 91.

2. Andrew Wilton, The Life and Work of J. M. W. Turner (Fribourg and London: Academy Editions, 1979), 310–12, nos. 89–95, 97.

3. Turner Bequest XIX 2 (Tate, D00208; catalogued by Andrew Wilton).

4. Turner Bequest XIX 19, 20 (Tate, D00227, D00228; both are also reproduced in Gerald Wilkinson, Turner’s Early Sketchbooks (New York: Watson-Guptill, 1972), 24. The second of these, taken from west side of the river, on the southern side of the bridge, was the source of the (now untraced) watercolor, developed for the Copper-Plate Magazine (see Wilton, The Life and Work of J. M. W. Turner, no. 90). The other sketch is more unusual in providing a detailed study of the northern side of the bridge, with the ruins of Bridgnorth Castle seen up on the hillside beyond.

5. Both the pencil drawing of about 1798 and the much larger watercolor of 1802 are in the British Museum. See Greg Smith, Thomas Girtin: The Art of Watercolour, exh. cat. (London: Tate Britain, 2002), 118, 230–31.

6. See https://www.thomasgirtin.com/collection/catalogue/bridgnorth-on-the-river-severn (accessed October 4, 2022). I would like to thank Greg for sharing his thoughts on this work, which have led me to rethink the dating of the present work since writing my article in 2019.

7. In light of the previous note, the idea of a visit in 1798, suggested in Ian Warrell, “Turner’s Bridgnorth,” Turner Society News 132 (Autumn 2019): 19–20, should be discarded; Turner’s route through this area that year seems to have been farther to the west of Bridgnorth. For the later visit, recorded in the Worcester, Shrewsbury, Bridgnorth, and the Peak sketchbook (Turner Bequest CCXXXIX; Tate), see Matthew Imms’s 2014 entries on the Tate website (https://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/jmw-turner/worcester-and-shrewsbury-sketchbook-r1148794#entry-main), dated to “?1831.” The present author simultaneously proposed the later date of 1834 in Warrell, Turner’s Sketchbooks (London: Tate Publishing, 2014), 172–73.

8. Thanks to churchwarden David Oxtoby for clarifying the history of St. Mary Magdalene.

9. Woolverhampton, exhibited 1796 (Wolverhampton Art Gallery). See Wilton, The Life and Work of J. M. W. Turner, no. 139; and Eric Shanes, Young Mr. Turner: The First Forty Years, 1775–1815, vol. 1 (London: Paul Mellon Centre, 2016), 125, fig. 152.

10. Buildwas Abbey, Shropshire, c. 1796–97 (Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester). See Wilton, The Life and Work of J. M. W. Turner, no. 247. For the untraced pencil sketch, see the transcriptions of the Cooper Notebooks in Martin Krause, Turner in Indianapolis (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997), 267, as one of a couple of sketches of “Buildas Abbey.” It is interesting to note that these are dated “1799,” though other details in the listing are not always accurate.

11. See also London from Lambeth, with Westminster Bridge, c. 1796 (Shanes, Young Mr. Turner, 120, fig. 147). Future analysis may determine whether these works made use of the same paper type. For more on Turner’s use of diverse papers, see Peter Bower, Turner’s Papers: A Study of the Manufacture, Selection and Use of His Drawing Papers 1787–1820 (London: Tate Gallery, 1990).

12. Llandeilo Bridge and Dynevor Castle, exhibited 1796 (National Museum of Wales, Cardiff). See Wilton, The Life and Work of J. M. W. Turner, no. 140; and Tim Barringer and Oliver Fairclough, Pastures Green and Dark Satanic Mills: The British Passion for Landscape (New York: American Federation of Arts, 2014), 94–95, no. 18. Another work of the same year is Aberdulais Mill, c. 1796 (National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth; Shanes, Young Mr. Turner, 118, fig. 142).

Bridgnorth on the River Severn (Shropshire)

Warrell, Ian. “Turner’s Bridgnorth.” Turner Society News 132 (Autumn 2019): 19–20.

ProvenanceMathers[?] sale, December 11, 1872, lot 85 (as A Bend on the River);[ Purchased by Agnews, London [stock number 1670] by 1872]; Purchased by James Worthington, May 21, 1873 (as A Bend on the River); Alfred Geoffrey Turner (1886-1956), Hungerford Park, Hungerford (as A Bend on the River); [his sale, at Hungerford Park, Hungerford, June 12-14, 1956]; Peter Rhodes, Oxford, at least by 1960; [Sotheby’s, London, Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century British Drawings and Watercolours, July 11, 1985, lot 108 (as “The Property of a Gentleman,” A View on the River Severn at Bridgnorth Shropshire)]; [Christie’s, London, British Art on Paper, November 21, 2001, lot 40]; [purchased by Andrew Clayton-Payne, London, 2001-2002]; Private Collection, UK, 2002-2018; [Andrew Clayton-Payne, London, 2018-2019]; purchased by MFAH, 2019.Comparative Images

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has made every effort to contact all copyright holders for images and objects reproduced in this online catalogue. If proper acknowledgment has not been made, please contact the Museum.