“Mons Rigaud about February . . . from Paris came over here at the request of Mr Bridgman [sic] the Kings Gardner. To be employd by him to make designs of Gardens. Views &c. of which at Ld Cobhams he has been some time made many drawings most excellently performd. He being perfect Master of perspective finely disposes his groups of Trees light. & shade & figures in a masterly manner.—some of the plates he has begun to Engrave.”1 This is how the antiquarian and engraver George Vertue succinctly recorded the arrival of the French landscape draftsman and engraver Jacques Rigaud in London in 1733. Rigaud had recently achieved significant success with a series of engravings, after his own drawings, Les Maisons Royales de France, published in 1730. The present drawing of the Rotunda at Stowe was one of those “excellently performd” drawings commissioned by Charles Bridgeman to commemorate his work in the garden created by Richard Temple, 1st Viscount Cobham at Stowe in Buckinghamshire.2 This large, impressive, and richly worked sheet was not one of those engraved, instead it offers a rare contemporary depiction of Britain’s greatest landscape garden, populated with fashionable visitors.

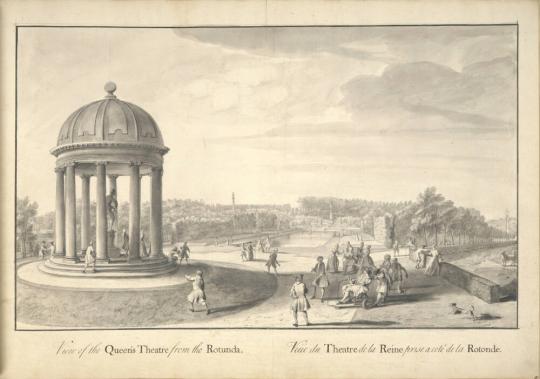

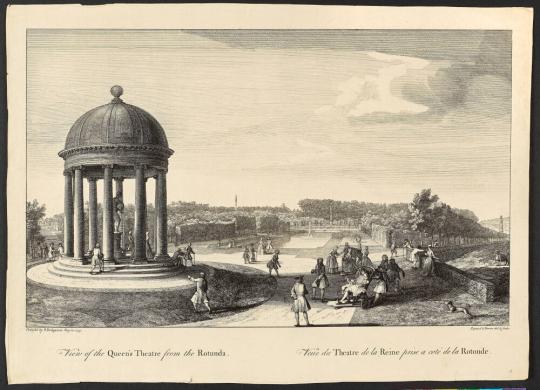

The gardens at Stowe were begun by Cobham shortly after he inherited the estate in 1713. He employed the Royal Gardener, Charles Bridgeman, to execute his plans. Cobham’s concept for the landscape at Stowe was ambitious. In 1717 he opened the New Inn on the outskirts of the grounds to accommodate tourists. Throughout the next couple of decades, Bridgeman extended the gardens further south, adding an octagonal lake, while a group of distinguished architects, including Sir John Vanbrugh and James Gibbs, contributed ornamental buildings. It was Vanbrugh who constructed the Rotunda, in 1720–21, as a circular temple consisting of ten unfluted Roman Ionic columns raised up on a podium of three steps designed to house a statue of Venus. The Rotunda is at the heart of Rigaud’s drawing. Bridgeman had placed the circular temple at the end of four radiating walks; Rigaud shows three of them dominated by the central walk of the Queen’s Theatre, which contained a formal canal basin and elaborate terracing. In the present sheet, Rigaud shows the Rotunda with some differences to the architecture—the columns are Doric, rather than Ionic, and the sculpture in the center is not Venus but the statue of Queen Caroline, which was eventually installed at the end of the Queen’s Theatre. This may explain why this view was not included among those engraved by Rigaud for Charles Bridgeman and why the present drawing was not among those included in an album now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (fig. 1.1).3 Rigaud did engrave an alternative view of the Rotunda, View of the Queen’s Theatre from the Rotunda, which shows the vista as it was in 1733 (fig. 1.2). As Peter Willis has pointed out, the gardens were changing at such a rapid rate at this date that Rigaud’s drawing may depict a projected alternative layout designed by Bridgeman.By Rigaud’s arrival at Stowe, the garden, as Cobham had intended, was already attracting considerable numbers of visitors: the antiquarian Sir John Evelyn described them in 1725 as “very noble,” and in 1724 John Percival, 2nd Earl of Egmont, noted that Stowe “has gained the reputation of being the finest seat in England. . . . The Gardens, by reason of the good contrivance of the walks, seem to be three times as large as they are.”4 Rigaud has filled his composition with fashionable figures admiring the new landscape, although this may equally reflect the convention of populating gardens with figures, as Rigaud had done in his engravings for Les Maisons Royales de France.

Rigaud’s drawings had been commissioned by Charles Bridgeman, who prepared a sumptuous publication of views of Stowe, plus a plan, that were engraved partly by Rigaud and partly by Bernard Baron. The publication did not appear until 1738, after Bridgeman had died and Rigaud had returned to France. Other English landscapes by Rigaud survive, including eight views of Lord Burlington’s villa at Chiswick in the collection of the Duke of Devonshire. —Jonny Yarker

Notes

1. Lionel Cust and Arthur Hind, eds., “The Notebooks of George Vertue,” Walpole Society 3 (1933–34): 69.2. The provenance for this drawing and others in the Stuart Collection are from the collection of the scion of a successful German banking family that had been established Britain since the early 1800s. Brandt started collecting in the 1940s and began buying in earnest toward the end of the 1950s, after which time he acquired drawings almost continually until his death. Though initially focused on contemporary art, Brandt grew increasingly interested in earlier work, and he eventually amassed one of the finest, most extensive collections of British drawings dating from 1650 to 1850; in particular, Brandt was a pioneering collector of Neoclassical and romantic drawings.

3. Peter Willis, “Jacques Rigaud’s Drawings of Stowe in the Metropolitan Museum of Art,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 6, no. 1 (Autumn 1979): 85–98.

4. Quoted in Peter Willis, Charles Bridgeman and the English Landscape Garden (Newcastle, UK: Elysium, 2002), 111.

The Rotunda at Stowe

- (not entered) The Audrey Jones Beck Building

Comparative Images

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has made every effort to contact all copyright holders for images and objects reproduced in this online catalogue. If proper acknowledgment has not been made, please contact the Museum.