Alexander Cozens was one of the most fascinating and at times notorious artists of the eighteenth century. His notoriety arose largely because of his complicated systems for inventing landscape compositions through the use of blots, of which this view of A Castle in a Landscape is a typical example. In his own time, Cozens was called “Blotmaster-General to the town” by a jealous rival and was even described as a charlatan in the next generation. These epithets colored his reputation until the rediscovery of his work and new research on his publications and methods in the twentieth century established him as a proponent of moral landscape painting and a significant writer on the theory and practice of art.1

Alexander Cozens was born in St. Petersburg to the son of one of Peter the Great’s English master shipbuilders; his godfather was Alexander Menshikov, the czar's greatest friend, and Cozens spent his younger years in close proximity to the Russian court before he was sent to England to study when he was ten. Decades later, he regaled his young pupil William Beckford with tales of the court and visiting dignitaries from the East, and Beckford nicknamed him “the Persian.”2 He was Beckford’s drawing master from the early 1770s, by which time he had been a private drawing master to various noble families and had been giving independent drawing lessons to pupils at Eton for the previous decade at least. He went on to teach Princes William and Edward, and the list of subscribers to his publication The Principles of Beauty Relative to the Human Head (1778) included the names of hundreds of the political, religious, noble, intellectual, and cultural leaders of the day.

His teaching is what inspired and led him to write his publications on how to invent landscapes through the use of blots, a method that was often misunderstood then, and indeed often is now. Many assume that the blots are similar to Rorschach blots, completely random and revealing of deeper psychological meaning, but this is far from the truth or from Cozens’s intention. The best way to understand their use and his purpose in creating blots is through his publications on them. The first, An Essay to Facilitate the Inventing of Landskips, Intended for Students in the Art, was published in 1759 as a booklet with a simple two-page text accompanied by eight pairs of etchings of the eight “Stiles of Composition,” each illustrated by a blot and an outline drawing made from it.3 His directions for making a blot in this first publication were substantially the same as those given in his final publication on blots, A New Method of Assisting the Invention in Drawing Original Compositions of Landscape, published in 1785, the year before his death. The method was described on page four of the 1759 booklet: "Take a Camel’s Hair Brush, as large as can be conveniently used, according to the intended Blot or black Sketch; dip it in Indian Ink dissolved in Water, and with the swiftest Hand make all possible Variety of Shapes and Strokes upon your Paper, confining the Disposition of the Whole to the general Form in the Example which you chuse [sic] for your Stile of Composition."

The pupil was instructed to lay a clean piece of thin post paper (in the later publication, he suggested oiled or varnished paper to make it more transparent) over the sketch and then draw a design from the hints that appear through the paper. The outline examples were provided to help make out the hints, but if pupils were practiced in drawing, they did not need to refer to the examples and instead could create the details from their own imagination, according to the text. In the longer description and explanation in the later version, Cozens defined a blot further, explaining: "It is not a drawing, but an assemblage of accidental shapes, from which a drawing may be made. It is a hint . . . of the whole effect of a picture, except the keeping and colouring; that is to say, it gives an idea of the masses of light and shade, as well as of the forms, contained in a finished composition. . . . To sketch is to delineate ideas; blotting suggests them."4

He also explained how to build up a finished landscape from a blot, by drawing details of figures, buildings, and other features in graphite on the varnished sheet and then selecting a sky and drawing in the clouds. The whole landscape should then be washed with the lightest tone, followed by progressively darker washes laid in the appropriate parts, in keeping with the mood of the landscape and the direction of the principal light.

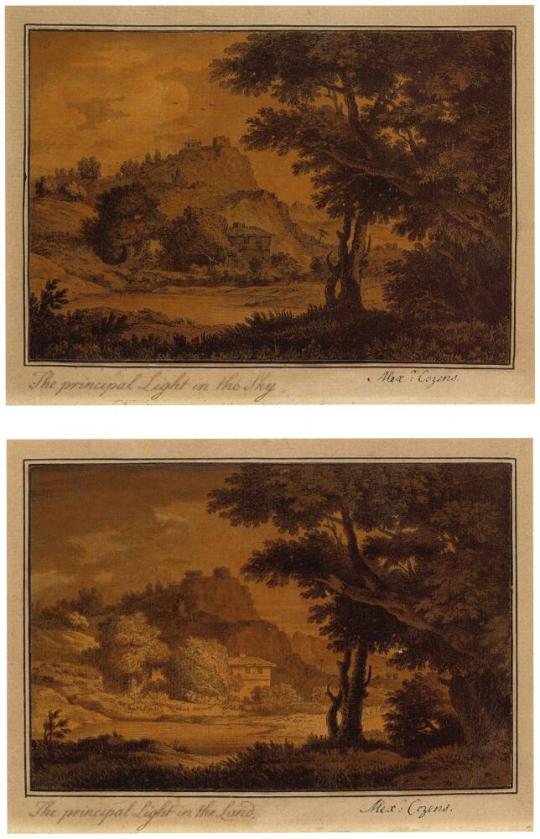

Both publications were accompanied not only by the illustrations but also by an exhibition of the blots and finished drawings that had been produced for the illustrations. In the earlier publication, the blots were closer to sketches, a little like the present drawing but without any background coloring or washes. The finished drawings that were exhibited were not like the outlines illustrated in the publication but detailed drawings, with figures, buildings, and other elements picked out in pen and ink and the whole carefully washed in grays or browns. They were shown in pairs, each demonstrating a different principle of shading, according the source of the light, for each style of composition. Two of these examples survive, produced to illustrate the “5th Stile of Composition,” chiefly of a group in the middle ground with the addition of a high tree in the foreground: one is labeled “The principal Light in the Sky,” and the other “The principal Light in the Land” (fig. 6.1).5 In the publication of 1785, the blots were on wrinkled paper and much darker, but still recognizably landscapes, while the finished drawings were completely washed and shaded in different tones to reflect different light sources or moods, and very similar to the landscapes in browns, grays, and yellows that Cozens produced in the 1780s.

Cozens continued to evolve his teaching method employing blots and styles of composition both for his pupils and in his own work, teaching by example but also exhibiting his blots and landscapes made from them at various Society of Artists exhibitions and others through the 1760s and 1770s. He doubled his number of “stiles of landscape composition” found in nature from eight to sixteen, and most of his works were exhibited in pairs or groups as “Landscapes: in brown.”6 In the 1770s, he exhibited oil paintings that demonstrated the “Circumstances” of landscape that he was working on at this time, such as Before a Storm, After a Storm, and so forth. The compositions of these works still conformed to his sixteen basic styles of composition, but with added elements demonstrating the effect of different light, skies, figures, buildings, and times of day. Most were probably also based on initial blots, like the present work. This one seems to conform to species of composition number one in the 1759 booklet, “A sea-coast or the banks of a river,” or number six in Various Species (see cat. 5), “A single object, or cluster of objects, at a distance.” It is on varnished paper or paper that has been prepared with a light yellow wash (mastic varnish, which he often used, can have a yellow tinge) that has been pasted on a thicker laid paper mount by the artist, given wash-line borders, and signed by him, possibly indicating that it was exhibited. Many similar blots survive.7 For instance, the British Museum has an album of dozens of examples, not mounted and signed but pasted into an album.8 In the present work, a yellow wash indicates the sky and clouds, while the landscape is washed with gray over the underlying darker sketch, in this case probably demonstrating that the principal light is in the sky.

However, the most fascinating aspect of Cozens’s blots is that they were not simply a slick didactic method for inventing landscape compositions. In that one held a specific type of composition in mind when creating them, they were tied to truth in nature and, through that, to moral improvement. This spiritually improving aspect of Cozens’s work was acknowledged by the Reverend Charles Davy, who wrote: "The general effect of a survey of Nature is Delight; whilst every species of Landscape, like every different species of Melody excites its own peculiar genuine emotions, nor are they limited to the imagination only, they make their passage through it to the heart, and lead to acts of Gratitude and Adoration . . . the dullest finds his mind exalted by the contemplating of Sublimity and Vastness . . . he who renders a man more easy with himself, renders him so to all Mankind."9

A surviving manuscript lists the emotions that the sixteen different styles of landscape composition should arouse and indicates that the spectator should be in a tranquil state of mind when observing them. The sentiments that should be aroused by composition six, as represented by the present work, are “unity of idea, influence around us, power, protection.”10 Alexander Cozens’s ability to use the elements of composition, light, and especially sky in a landscape to produce states of mind was something that his son, John Robert, not only understood but used to the greatest effect in his own watercolors. —Kim Sloan

Notes

1. See Kim Sloan, Alexander and John Robert Cozens: The Poetry of Landscape (New Haven: Yale University Press; Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario), 87.

2. Sloan, Alexander and John Robert Cozens, 73–78.

3. Discussed, transcribed, and reproduced in full in Kim Sloan, “A New Chronology for Alexander Cozens: Part II,” Burlington Magazine 127, no. 989 (June 1985): 355–63.

4. Alexander Cozens, A New Method of Assisting the Invention in Drawing Original Compositions of Landscape (London: printed for the author, [1785]), 8–9, reproduced in Alexander Cozens, A New Method of Landscape (London: Paddington Press, 1977).

5. See Christie’s, “Sale: Old Master & 19th Century Paintings, Drawings & Watercolours, London,” July 7, 2010, lot 374, at https://www.christies.com/lot/lot-5334398.

6. Andrew Wilton, The Art of Alexander and John Robert Cozens (New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, 1980), 14.

7. See, for example, the blot in Castle by a Lake and Mountain, one of his earliest, signed and dated July 6, 1755 (Whitworth [D.1912.14]), and the blot in A Coastline, with Sea to Right, and Ships, inscribed “1st Stile of composition” (Tate Britain [T08020]).

8. See Kim Sloan and Paul Joyner, “A Cozens Album in the National Library of Wales,” Walpole Society 57 (1995): 84–93.

9. The asterisk in the text cited Cozens, see Sloan, Alexander and John Robert Cozens, 57.

[1]0. Sloan, Alexander and John Robert Cozens, 56.

A Castle in a Landscape

Cozens, Alexander. A New Method of Landscape. London: 1786.

Provenance[Spink-Leger, London, 1999]; [Christie’s, London, British Art on Paper, June 3, 2004, lot 61]; private collection, United Kingdom, 2004; acquired by [Lowell Libson and Jonny Yarker, Ltd., 2016-2018]; purchased by MFAH, 2018.Comparative Images

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has made every effort to contact all copyright holders for images and objects reproduced in this online catalogue. If proper acknowledgment has not been made, please contact the Museum.