Francis Towne made this powerful drawing in July 1781, during a final burst of creativity as he prepared to return home to England, at the end of a year exploring the great ruins and vistas of Italy, rich in classical and artistic associations.

Towne produced the most commanding and progressive work of his life abroad, but when he reached Rome, in October 1780, the city unsettled him. His great friend, the Exeter lawyer James White (1744–1825), argued in vain that language difficulties and other travel inconveniences were no reason to abandon his studies: Towne was “in the very Country where you ought to spend as much Time as possible upon every account and where the wonders of both art and nature cannot be properly and thoroughly examined in a very short time.”1 Yet by early March 1781, when Towne left Rome to visit the Welsh painter Thomas Jones (1742–1803) in Naples, he had determined to return to England that summer. In the remaining time, he returned to Rome only intermittently, instead sketching in the campagna, the Roman countryside “formed in a peculiar manner by Nature for the Study of the Landscape-Painter,” in Jones’s words.2

The decision to return home appears to have released Towne, for these final months were experimental and productive, yielding in half the time as many drawings as he had made in Rome. Towne visited Tivoli in May, and the Alban hills in June and early July, sketching at Rocca di Papa, Monte Cavo, Frascati, Nemi, Albano, and Arricia. Italy in the 1780s witnessed a regeneration in the study of nature by landscape painters, manifested chiefly through developments in the use of watercolor. The writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe reported the impression made on fellow artists by innovative contemporaries of Towne, like the Hackert brothers: “[Artists] marvelled when the two Hackerts went out to the Campagna with large folios and drew all their outlines in pen, or when they saw watercolors painted entirely from life.”3 Towne assimilated such ideas from his new working environment, and that summer the campagna was his platform for investigating new ways of working, such as coloring directly on the spot and the abandonment of outline. Towne’s sketching partner was John “Warwick” Smith (1749–1831), who was also his traveling companion through northern Italy and over the Alps back to London.

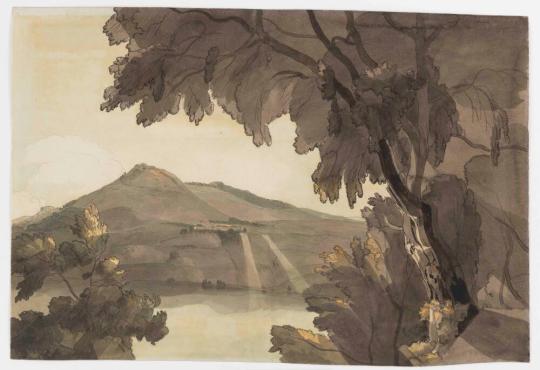

Lake Albano exemplifies these weeks of exploration of the expressive possibilities of the watercolor medium. Towne pushes freely at the conventions of pen and wash drawing, effectively abandoning outline in much of the composition where the wavy lines of the path on the left dissolve into nothing as it travels the lower margin of the sheet. The study’s most striking feature is its admixture of precise and careful outlines with bold and free wash strokes. Towne’s organizing focus is the dazzling effects of the sun that dominates the left half of the sheet. He captures its overwhelming power in free and angular marks with the brush, imposed on a neat and orderly line drawing. Watercolor painters of the following generation—spearheaded by Joseph Mallord William Turner and Thomas Girtin—would more decisively set aside the outline, and thereby unlock new painterly opportunities for the medium. Although in Lake Albano Towne worked within the tradition of wash and line, one can see his efforts to transcend its familiar limits, of describing and defining, and to deploy it instead to evoke and emote.

In Lake Albano, Towne also returned to a theme he had explored four years earlier, sitting by the river Dee near Llangollen in North Wales on July 17, 1777, with his friend James White. There, Towne drew several riverbank studies that, like Lake Albano, exploit the artistic potential of the sun setting behind trees over water. Writing to Towne in Italy, White could not “help fancying that your Present Tour is only a Welch Expedition upon a grander Scale.”4 A comparison of Lake Albano with the largest Dee study, which White commissioned as an oil, demonstrates the evolution that Towne’s artistic practice underwent in Italy. There, he learned to deploy scale, mass, and contrast to offer the viewer a more immediate encounter with his view and greater emotional involvement. The open skies and topographically detailed descriptions of 1777 give way in Lake Albano to a denser scene dominated by foreground trees, through which the viewer obtains no more than suggestive glimpses of the lake and hills beyond. In Wales, Towne kept the viewer at some distance from the depicted landscape, whereas in Lake Albano the scale and proximity of the shaded trees situate the viewer within their immediate vicinity, as if inhabiting the scene. Towne was to deploy this new visual language to dramatic effect in his sketches of the Alps made en route to England only weeks later.

Only four Alban studies have dates, beginning with Lake Albano, which Towne drew on the evening of July 10 above the eastern shore of the lake, looking at the sun setting in the west. The next morning, he was at nearby Arricia (as documented in a work in the British Museum), then on the morning of July 12 he returned to Lake Albano to make two further studies, one a canonical view of Castel Gandolfo overlooking the lake (also in the British Museum), and the other a morning view taken from the opposite side from Lake Albano that, with the sun rising over the hill town of Rocca del Papa (fig. 12.1), might be considered its companion. These were the final studies Towne made in the Roman countryside.

Towne’s Italian sketches remained mostly unmounted and in various states of completion until late in the artist’s life. He found a reasonable market for Roman and Neapolitan subjects, but campagna views were rarely commissioned. Lake Albano is thus a notable exception, for in 1784 Towne painted a version of it in oils for the brewer and merchant James Curtis (1750–1835) of Old South Sea House, London. The painting is lost, but the copy Curtis ordered of Arricia at the same time is in a U.S. private collection. Curtis is notable too as the only one of Towne’s customers not based in the West Country. Instead, their connection was a London wine merchant, Samuel Edwards of Beaufort Buildings, Strand. Curtis was the executor and principal beneficiary of Edwards’s will, indicating that the two had a close and longstanding financial relationship. Edwards was related by marriage to Towne’s close friend William Pars, whose brother, the drawing master Henry Pars (1736–1806), was Edwards’s brother-in-law. Towne himself had given Edwards power of attorney over his savings during his absence in Italy, indicating their bond.

Though Towne sought election to the Royal Academy of Arts on ten occasions during his post-Italian career, his achievements were not recognized by his contemporaries. In an attempt to secure his reputation posthumously, and as a memorial to his friendship with William Pars, whose watercolors were also held there, Towne bequeathed to the British Museum his series of views of Rome. The remainder of his studio, and the greatest part of the drawings by Towne that survive today, were bequeathed by Towne to a former pupil, the Exeter lawyer and poet John Herman Merivale (1779–1844). Lake Albano is one of hundreds of sheets that lay undisturbed at Barton Place, Merivale’s house near Exeter, throughout the nineteenth century, so that by the early 1900s they retained their freshness and vitality. They came to notice through the research of the scholar and collector Paul Oppé (1878–1957), who encountered the Merivale family in the 1910s. Oppé introduced Towne’s work to early twentieth-century eyes, which found in its clarity and angularity a disconcertingly contemporary vision for landscape, one that seemed to prefigure modern art movements. On one occasion, Towne was even mistaken for an unknown young artist by the leading British modernist Ben Nicholson (1894–1982).

In 1915 Merivale’s grandchildren moved out of Barton Place, and Towne’s bequest was divided between several cousins. Lake Albano went with the largest portion to the north Oxford house of two sisters, the Misses Merivale. Over the next thirty years, the younger, Judith Ann Merivale (1860–1945), sold off hundreds of Towne’s works through deft sales to dealers, collectors, and museums, thereby cementing his new reputation. Lake Albano was purchased in 1933 by the dealer Bernard Milling (1898–1954), whose Squire Gallery was, with Thomas Agnew & Sons, the principal retail outlet for early English drawings. It is a mark of the sheet’s significance within Towne’s oeuvre that Milling selected it on what was his first buying visit to Miss Merivale, for, at that point, he had almost the entirety of Towne’s oeuvre from which to choose. On the same visit, Milling bought the companion study of Lake Albano (fig. 12.1). Milling sold Lake Albano to his old friend Leonard Duke CBE (1889–1971), who formed one of the largest twentieth-century collections of early English drawings, often enlarged and refined through sales or exchanges within his circle. Thus, in 1955, Duke passed on the Lake Albano study to a friend, Nigel Warren QC (1912–1967), of Lincoln’s Inn, whose descendants sold it in 2002. —Richard Stephens

Notes

1. Paul Mellon Centre, London, Oppé Archive, APO/1/21/4: James White to Francis Towne, March 12, 1781 (transcript).2. Thomas Jones, ed. Paul Oppé, “The Memoirs of Thomas Jones,” Walpole Society 32 (1951): 66.

3. Quoted in Charles Bell and Thomas Girtin, “The Drawings and Sketches of John Robert Cozens,” Walpole Society 23 (1935).

4. Paul Mellon Centre, London, Oppé Archive, APO/1/21/4: James White to Francis Towne, May 4, 1781 (transcript).

Lake Albano

- (not entered) The Audrey Jones Beck Building

Comparative Images

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has made every effort to contact all copyright holders for images and objects reproduced in this online catalogue. If proper acknowledgment has not been made, please contact the Museum.