Lear’s interest in camels can be traced back to a letter he wrote to his sister, Ann, between January 16 and February 3, 1846, from “the desert: outside the walls of Suez.” In it, he describes his experience of these “beasts of burden.” He compares the enjoyable feeling of riding one to sitting “on a rocking chair,” but found them to be easily irritated: “If you try to make them go faster—they grown [sic] . . . if you stop them or try to go slower—they growl also.”3

Dromedaries had been kept at the Gombo since at least 1622, when they were first introduced from North Africa by Grand Duke Ferdinand II of Tuscany. Others were added to the herd after the success of General Arrighetti against the Turks before the Battle of Vienna in 1683. New stock was imported by the Tuscan government from Tunisia in 1782, and the herd grew to more than two hundred. Lear would have experienced fewer animals, as the numbers diminished as a result of the Napoleonic Wars.4

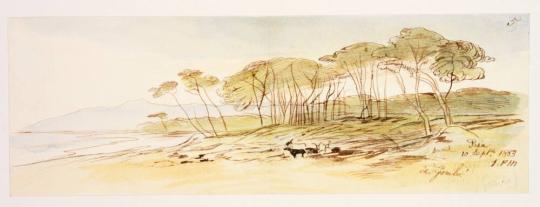

Lear continued to record his drawing itinerary, noting that “only 4 pieces of the small paper being now left, I came at 11 to the Gombo, I walked . . . to the sea, where I drew the coast line—very near to where Shelley’s body must have been found. The whole seems before me as I write, as it did 22 years ago (1861) when I drew the coast nearer Spezia . . . with quiet and space of this lovely coast to day!!! . . . goats only about and no humanity.”5 He remarks on where the body of the English romantic poet, Percy Bysshe Shelley, was washed ashore after a boat accident in 1822 and records other drawings that he made in rapid succession along the coastline, which have a similar color palette, indicate the time of day, and are numbered “4” and “5” (fig. 58.1).6 He left for Spezia on September 11, then Genoa on September 12, and returned home to San Remo on September 13. —Dena M. Woodall

Notes

1. See Edward Lear, Edward Lear Diaries, 1858–1888, MS Eng 797.3 (26), September 9, 1883, Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

2. See ibid., September 10, 1883.

3. Edward Lear, letter to Ann Edward Lear, January 16–February 3, 1849, Box: 1, Folder: 1 [MSS 59], Archive, Yale Center for British Art, gift of Donald C. Gallup.

4. Jefferson Davis, then secretary of war for the United States, began an experiment for the efficacy of using the camel for military purposes in Texas, New Mexico, and California, and on a camel-purchasing expedition to Europe and the Middle East, a lieutenant porter of the United States Army visited the “camel park” at San Rossore in the mid-1860s and was impressed by the herd of 250 and the loads borne by the camels but “considered those he saw in Tuscany to be overworked and badly cared for.” See Walter L. Fleming, “Jefferson Davis’s Camel Experiment,” Popular Science Monthly 74 (February 1909): 141–52, and A. G. Leonard, The Camel: Its Uses and Management (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1894), 13.

5. See Lear, Edward Lear Diaries, 1858–1888, September 10, 1883.

6. Edward Lear, [Near] Pisa: Gombo, September 10, 1883 (4), watercolor and sepia ink over graphite on cream paper, Harvard University, Houghton Library [MS Typ 55.11, MS Typ 55.26, TypDr 805.L513, 3528], and Edward Lear, Pisa, September 10, 1883 (5), watercolor and sepia ink over graphite on cream paper, Rhode Island School of Design Museum, anonymous gift [2005.142.112].

The “Gombo,” Pisa

Chitty, Susan. That Singular Person Called Lear: A Biography of Edward Lear, Artist, Traveller, and Prince of Nonsense. New York: Atheneum, 1989.

Fleming, Walter L. “Jefferson Davis’s Camel Experiment.” Popular Science Monthly 74 (February 1909): 141–42.

Garvey, Eleanor. Edward Lear: Painter, Poet, and Draughtsman, an Exhibition of Drawings, Watercolors, Oils, Nonsense and Travel Books. Worcester, MA: Worcester Art Museum, 1968.

Hofer, Philip. Edward Lear as a Landscape Draughtsman. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1967.

Lear, Edward. The Travels of Edward Lear: Exhibition October 17–November 11, 1983. London: Fine Art Society, 1983.

Lehmann, John. Edward Lear and His World. New York: Scribner, 1977.

Noakes, Vivien. Edward Lear: The Life of a Wanderer. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1969.

Noakes, Vivien. The Painter Edward Lear. London: David & Charles; Devon: Newton Abbot, 1991.

Noakes, Vivien, Steven Runciman, and Jeremy Maas. Edward Lear, 1812–1888. London: Royal Academy of Arts; New York: H. N. Abrams, 1986.

Nugent, Charles. Edward Lear the Landscape Artist: Tours of Ireland and the English Lakes, 1835 & 1836. Grasmere, UK: Wordsworth Trust, 2009.

Peck, Robert McCracken. “The Remarkable Nature of Edward Lear.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 162, no. 2 (June 2018): 158–90.

Wilcox, Scott, and Eva Bowerman. Edward Lear and the Art of Travel. New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, 2000.

Provenance[James Mackinnon, Midhurst, West Sussex], by 2016; purchased by MFAH, 2016.Comparative Images

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has made every effort to contact all copyright holders for images and objects reproduced in this online catalogue. If proper acknowledgment has not been made, please contact the Museum.