Thomas Girtin was the exact contemporary of Joseph Mallord William Turner. Born the same year, they were both prepared in the eighteenth-century topographical tradition, and Girtin was apprenticed to Edward Dayes in 1789 for a few years, having several duties to perform in his teacher’s workshop, including adding watercolor washes to his master’s prints. In the mid-1790s, both Girtin and Turner worked for the well-off linen draper, antiquarian, and amateur artist James Moore, producing watercolors after Moore’s sketches, mainly from his travels.1 Girtin first debuted his work at the Royal Academy of Arts in 1794, and from then until 1797 Girtin and Turner sketched in the evenings at the informal Monro Academy of Arts, founded by their shared patron, the physician Dr. Thomas Monro.2 Early in the careers of Girtin and Turner, they exchanged the tinted drawing tradition for the medium of watercolor due to its expressiveness and atmospheric effects. Girtin went on sketching tours in England, first with James Moore in 1794 and then independently between 1796 and 1799 to other regions in England, including Scotland and Wales, selling his watercolors to eager collectors. In 1799 Girtin founded the Sketching Society, called “The Brothers,” who “met for the purpose of establishing by practice a school of Historic Landscape” and creating landscape compositions based on passages from Romantic landscape poetry.3 In late 1801 to early 1802, he traveled to Paris in hopes of improving his health and painted watercolors and produced sketches in graphite. Shortly before dying at the age of twenty-seven, he exhibited in 1802 his massive panorama of London, Eidometropolis, and his Parisian drawings were posthumously published in an engraved series, Twenty Views in Paris and Its Environs. Turner, who lived until 1851, apocryphally stated, “Had Tom Girtin lived, I would have starved.”

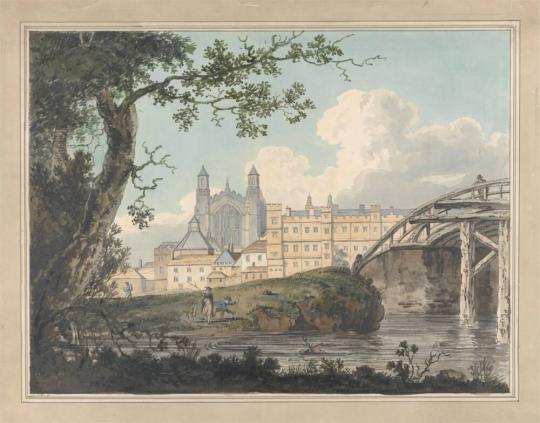

Rochester Castle from the River Medway depicts Rochester Castle, the Bridge Chapel and Chamber, and the medieval Rochester Bridge crossing the Medway River in Kent, east of London. The viewpoint is from the other side of the river, looking toward the bridge and the imposing castle. Fishermen in small boats dock next to the riverbank, and a tall wooden mill building with a stone foundation sits on Strood Wharf.4 This watercolor advances our understanding of Girtin’s exceptional talent by the age of sixteen. Dating from about 1791–92, it joins a small group of large-scale compositions that Girtin produced only a few years into his apprenticeship with Edward Dayes. It reflects Dayes’s teaching, as noted in his writing on watercolor practice.5 Dayes understood which pigments were most steadfast, and he passed this knowledge on to Girtin. Girtin’s adoption of Dayes’s palette is seen here in the relatively limited color palette of blues, grays, browns, and ochres.6 Yet Girtin’s treatment of light and shade and his subtle color treatment indicate that he was beginning to interpret the landscape, moving past the strictly topographic tradition. The artist’s handling of the water and the sky makes this evident. The low vantage point emphasizes the castle’s massive structure. It is bathed in light, contrasting with the darkened Strood tide mill on the wharf. The sky is composed of bare paper, gray washes, and small areas of blue. Streaming sunlight invigorates the stonework of the castle and bridge. Girtin’s application of watercolor for the river also displays his mastery, with horizontal bands of darker wash running over a lighter base, creating a mosaic effect, while other complex areas display patterns of reflected light.

This composition can be compared to two other large-scale watercolors by Girtin focusing on architectural structures, inscribed 1790—Eton College from Datchet Road (fig. 27.1) and Durham Cathedral and Castle.7 For these compositions and Rochester Castle from the River Wegway, Girtin probably based his views on drawings by Dayes, since, as a young apprentice, he was unable to travel to those locations. Dayes’s drawings of Durham Cathedral from the late 1780s were resources for Girtin’s portrayal, but comparable sketches by Dayes have not yet been found for Eton College from Datchet Road. Girtin made four watercolors of Rochester in 1791–92, and he most likely used Dayes’s topographical sketches from his travels there in the late 1780s as the basis for these compositions.8 The other early compositions by Girtin are less painterly than this view of Rochester, which is a striking precursor to Girtin’s mature watercolors. As Greg Smith suggests, these works by Girtin were not “simple studio exercises”; by 1791 Dayes had sent watercolors by the young Girtin to the London auction house of Thomas Greenwood, including Rochester Castle from the River Medway for the auction of January 24–25, 1792, as “Drawings, Framed and Glazed.” This exquisite watercolor with its added wash-line mount would have enticed collectors.9 —Dena M. Woodall

Notes

1. See Greg Smith, “Thomas Girtin (1775–1802): A Short Life Story,” in Thomas Girtin (1775–1802): An Online Catalogue, Archive and Introduction (London: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2022).

2. “Turner & Girtin told us they had been employed by Dr. Monro for 3 years to draw at his house in the evenings. They were at 6 and staid till Ten. Girtin drew in outlines and Turner washed in the effects. They were chiefly employed in copying the outlines of unfinished drawings of Cozens &c &c. of which Copies they made finished drawings.” See Joseph Farington, The Diary of Joseph Farington, vol. 3, September 1796–December 1798, ed. Kenneth Garlick and Angus Macintyre (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1979), 1090.

3. See Dr. Guillemard, “Girtin’s Sketching Club,” Connoisseur 63 (May–August 1922): 189.

4. Girtin’s dark wooden building on the wharf was the Strood tide mill, which was in existence since the post-medieval period and belonged to the dean and chapter of Rochester and by about the eighteenth century to the Hulkes family. There was a quay nearby with a fisherman’s exchange and a coal shed. Though in Girtin’s composition the mill appears to be on a high stone wharf next to the medieval bridge, the wharf was much lower. William Hogarth, when he was making his celebrated Tour in Kent, sketched the mill from Rochester Bridge. See William Hogarth, A View from Rochester Bridge, 1792, etching and aquatint, collection of Yale University Library. Other artists portrayed the castle from a similar vantage point as Girtin, suggesting that Girtin aggrandized the building for more dramatic effect. See Joseph Constantine Stadler, after Joseph Farington, Rochester Bridge and Castle, published June 1, 1793, aquatint with hand coloring, from A History of the River Thames, published by John and Joshia Boydell, June 1, 1793, at the Shakspeare Gallery Pall Mall, & No. 90, Cheapside, William Alexander, Rochester Castle from the River, c. 1800, graphite and gray wash on paper, London, Roseberys, Old Masters, British & European Pictures, March, 29, 2023, lot 121. I am grateful to Craig S. Calvert in conversation with Alison Cable, archives manager, Rochester Bridge Trust; see correspondence, January 16–17, 2024, curatorial files, prints and drawings, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

5. See Smith, “Thomas Girtin (1775–1802): A Short Life Story,” n21.

6. This watercolor is in splendid condition. Each tone is distinguishable against the light ground of the paper support, suggesting that it was carefully hung on a wall or more likely sequestered in a portfolio, retaining the freshness of the colors.

7. Thomas Girtin, Durham Cathedral, from the River Wear, 1790, graphite, watercolor, and pen and ink on paper, on an original mount, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia [ОГ-11819].

8. A drawing by Dayes from a similar vantage point but not entirely consistent with the elements in Girtin’s watercolor is at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, therefore he must have derived it from an untraced sketch. See Edward Dayes, Rochester Bridge and Castle, no date, watercolor and pen and ink on paper, private collection, in Greg Smith, Thomas Girtin (1775–1802): An Online Catalogue, Archive and Introduction (London: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2022), cat. 0057, fig. 1, illus. Girtin made four watercolor views of Rochester, including this one, during his apprenticeship to Dayes. The others are Rochester from the Bank of the River Medway, 1791, graphite, watercolor, and pen and ink on wove paper, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven [B1975.3.1139]; Rochester Cathedral and Castle, from the North East, 1792–93, graphite, watercolor, and pen and ink on wove paper, Eton College, Windsor [FDA-D.262-2010]; Rochester, from the North, 1791–92, graphite and watercolor on wove paper, on an original gray and blue wash-line mount, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven [B1975.3.1023]. See Smith, Thomas Girtin (1775–1802): An Online Catalogue, Archive and Introduction, cats. TG0015, TG0076, and TG0071.

9. Eton College was possibly at auction at Greenwood’s on June 10, 1791, as part of lot 37, listed as “Two views of Windsor and Eton.” This watercolor was in day two of the Greenwood sale as lot 69. See Frits Lugt, Repertoire des catalogues de ventes publiques interessant l’art ou la curiosité, vol. 1 (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1938–87), cat. 4839, and Smith, Thomas Girtin (1775–1802): An Online Catalogue, Archive and Introduction, cats. TG0013 and TG0057.

Rochester Castle from the River Medway

Baker, Christopher. English Drawings and Watercolours 1660–1900. Edinburgh: National Gallery of Scotland, 2011.

Farington, Joseph. The Diary of Joseph Farington. Vol. III, September 1796–December 1798. Edited by Kenneth Garlick and Angus Macintyre. London: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art; New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979.

Girtin, Thomas. “Girtin’s Earliest Known Work.” Burlington Magazine 94, no. 589 (April 1952): 112–13, 115.

Girtin, Thomas, and David Loshak. The Art of Thomas Girtin. London: A. & C. Black, 1954.

Hardie, Martin. “A Sketch-Book of Thomas Girtin.” Walpole Society 27 (1938–39): 89–95.

Hardie, Martin. Water-Colour Painting in Britain II: The Romantic Period. London: B. T. Batsford, 1967.

Hargraves, Matthew. Great British Watercolors from the Paul Mellon Collection at the Yale Center for British Art. New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, 2007.

Hill, David. Thomas Girtin: Genius in the North. Leeds, UK: Harewood House Trust, 1999.

Kitson, Michael. “Thomas Girtin.” Burlington Magazine 117, no. 865 (April 1975): 256–57.

Loshak, David. “Thomas Girtin.” Art Journal 20, no. 1 (Autumn 1960): 28–30.

Lugt, Frits. Repertoire des catalogues de ventes publiques interessant l’art ou la curiosité: Periode 1 vers 1600–1825; Periode 2 1826–1860; Periode 3 1861–1900; Periode 4 1901–1925. 4 vols. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1938–87.

Pyne, W. H. “Observations on the Rise and Progress of Painting in Water Colours.” Repository of Arts 8 (November 1812–March 1813): 23–27, 257–60, 324–27.

Smith, Greg, ed. Thomas Girtin: The Art of Watercolour. Exh. cat. London: Tate Gallery, 2002.

Smith, Greg. Thomas Girtin (1775–1802): An Online Catalogue, Archive and Introduction. London: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2022.

Wilton, Andrew, and Anne Lyles. The Great Age of British Watercolors, 1750–1880. London: Royal Academy of the Arts; Washington DC: National Gallery of Art, 1993.

Provenance[Possibly London, Thomas Greenwood, Some Exceedingly Fine Modern Drawings, Framed and Glazed, January 25, 1792; lot 69 (as Rochester Castle and Bridge)]; Private collection, England; [Andrew Clayton-Payne, London, 2013–2016]; purchased by MFAH, 2016.Comparative Images

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has made every effort to contact all copyright holders for images and objects reproduced in this online catalogue. If proper acknowledgment has not been made, please contact the Museum.