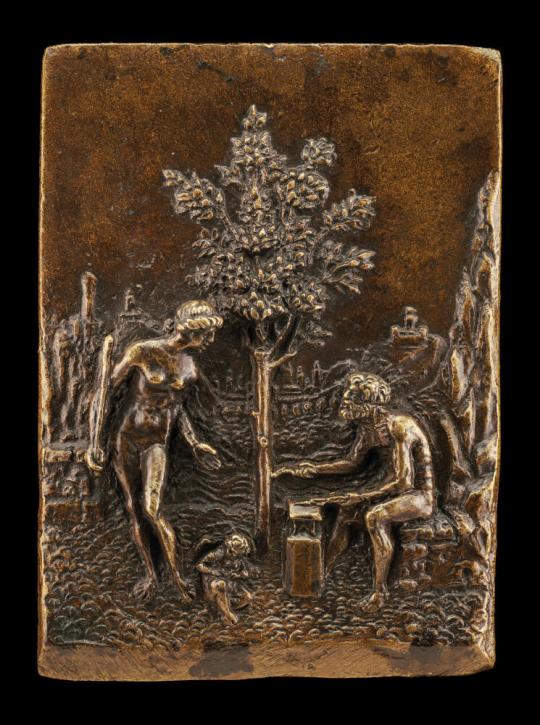

The circular relief depicts Vulcan at his forge with Venus and Cupid. Vulcan, bearded and naked, is seated at his forge in an extensive landscape; he holds a hammer in his raised right hand, and in his left he uses a pair of tongs to grasp an object that he is working. It is not easy to make out if this is an arrow or one of the wings of Cupid, but Cupid appears to be missing a wing, so it may well be that Vulcan is forging the wings of the god of love, seated on the ground and playing with an arrow. Vulcan looks up and seems to be conversing with the naked figure of Venus, who stands at the left in an elegant contrapposto pose, holding a staff. There is a tree in the center and a city in the background at right. A sloping, plain exergue is at the bottom of the obverse; a small suspension hole is at top center. On the reverse, in raised relief, appears the signature “R º I,” at 180 degrees to the obverse design.

Vulcan (Greek: Hephaestos) was the Roman god of fire and a blacksmith, who forged the weapons used by many gods and mythological heroes. The son of Jupiter and Juno, Vulcan was the husband of Venus, god of love, who cuckolded him with the god Mars, the shepherd Adonis, and many others. Unlike male deities such as Mars or Apollo, who are generally pictured as handsome young men in the prime of life, Vulcan is usually depicted as a mature or even elderly individual.

The plaquette shows the theme, popular in Italy in the years around 1500, of Vulcan forging the wings of Cupid. Although Vulcan and Venus were consorts, Cupid is generally thought to have been the fruit of Venus’s liaison with the god of war, Mars, although the iconography is sometimes confused. Thus, in the plaquette in the Straus collection of Venus Chastising Cupid (44.595), Venus berates her son after he caused her disgrace before the gods by kindling an illicit passion between her and Mars. The Vulcan Forging the Wings of Cupid also relates to the figure of Vulcan in the Straus Collection (44.585), giving a helpful sense of the likely original context for that bronze figure. Like it, the plaquette design may be compared with contemporary prints of the subject.

As with the other plaquettes acquired by Percy Straus, the Vulcan Forging the Wings of Cupid was sold to him by Simon Meller through the agency of Leo Planiscig. Planiscig wrote to Straus shortly before Christmas 1936, explaining that Meller had asked Planiscig to offer the plaquette to Straus for a price of 40,000 francs. Straus must have replied expressing interest but stating that the price was too high since in a subsequent letter, Planiscig confirmed that he would write to Meller to this effect.1 It is not known what the final agreed price was.

As Planiscig noted in his first letter to Straus, another closely similar example of this design, with the same signature on the reverse, is in the Staatliche Museen, Berlin,2 while a rectangular version was at that time in the Gustave Dreyfus collection and is today in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.3 The rectangular version shows signs of having been adapted from the circular tondo format, which must therefore be regarded as the original shape. Planiscig also cited a variant circular design, also now in the National Gallery of Art and from the Dreyfus collection, in which the figures are reversed.4 As Pope-Hennessy noted, Planiscig was incorrect in his assumption that the two designs are variants of the same model. Although stylistically the Washington plaquette forms part of the same group, the figures are quite different in conception, so they really have little in common with the present design, beyond their subject.

The rectangular version of Vulcan Forging the Wings of Cupid was the first to be published, by Gaston Migeon in 1908, as the work of Riccio,5 an attribution that has until recently been universally accepted, not least because of the presence on the reverse of the artist’s signature. However, it is part of the group of plaquettes (see also cat. 55, 44.593, and cat. 56, 44. 595), some examples of which apparently bear the signature of Riccio, but which stylistically have little to do with that artist’s style as we understand it, and as it may be seen in securely autograph plaquettes and reliefs, such as the small circular allegorical scenes or the reliefs of the Entombment.6 The scalloped modeling of the ground is identical to the foreground in the plaquette of the Death of Dido in the Straus Collection (cat. 55, 44.593), and may also be seen in the variant Vulcan Forging the Wings of Cupid and in a plaquette of Prudentia, which is similar to the Dido in concept.7 Bertrand Jestaz in 1989 noted the similarities in the handling of the ground and landscape with the Dido, stating that in his view the figure style had nothing to do with Riccio.8

Carolyn Wilson more recently attributed the work to an anonymous associate of Riccio. We know nothing about Riccio’s workshop and how it was composed and functioned, other than that his father Ambrogio di Cristoforo (died 1525) was a goldsmith and that Riccio worked in some way with him,9 as did Riccio’s two brothers Battista and Galvano. Perhaps some form of joint workshop operated in which small reliefs designed by other members of the workshop were issued, bearing Riccio’s signature as a type of workshop mark. In the present state of knowledge, it seems best to regard a work such as the Vulcan Forging the Wings of Cupid as likely to be a product of Riccio’s workshop.

—Jeremy Warren

Notes

1. Leo Planiscig to Percy S. Straus, January 18, 1937, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, archives.

2. Inv. 1921. E. F. Bange, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin: Die italienischen Bronzen der Renaissance und des Barock, II, Reliefs und Plaketten (Berlin: Staatliche Museen Zu Berlin, 1922), 49, no. 361, Taf. 36; Leo Planiscig, Andrea Riccio (Vienna: H. Schroll, 1927). 439–40, Abb. 529–30.

3. Inv. 1957.14.260. Planiscig, Andrea Riccio, 439–41, Abb. 532; John Pope-Hennessy, Renaissance Bronzes from the Samuel H Kress Collection: Reliefs, Plaquettes, Statuettes, Utensils and Mortars (London: Phaidon for the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, 1965), 63, no. 211, fig. 109.

4. Inv. 1957.14.259. Planiscig, Andrea Riccio, 439–41, Abb. 531; Pope-Hennessy, Renaissance Bronzes 63, no. 210, fig. 110.

5. Paul Vitry, Jean Guiffrey, and Gaston Migeon, La Collection de M. Gustave Dreyfus (Paris: Manzi, Joyant & Cie, 1908), 90.

6. See for these Pope-Hennessy, Renaissance Bronzes, nos. 203–07, 219–24.

7. Bange, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 51, no. 375, Taf. 37; Planiscig, Andrea Riccio, 438–39, Abb. 528.

8. Bertrand Jestaz, “Riccio et Ulocrino,” in Italian Plaquettes (Proceedings of the Symposium “Italian Plaquettes,” 1-22 March 1985), ed. Alison Luchs (Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1989), 194.

9. For Ambrogio di Cristoforo’s Reliquary of the Eyelash of Saint Anthony (c. 1510–11) in the Basilica di Sant’Antonio, Padua, see Davide Banzato and Elisabetta Gastaldi, Donatello e la sua lezione: Sculture e oreficerie a Padova tra Quattrocento e Cinquecento (Milan: Skira Editore, 2016), 119, no. 54.

Vulcan Forging the Wings of Cupid

Bange, E. F. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. Die italienischen Bronzen der Renaissance und des Barock. II. Reliefs und Plaketten. Berlin: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 1922.

Cassirer, Paul, and Hugo Helbing. Die Sammlung Dr. Eduard Simon, Berlin. Erster Band. Gemälde und Plastik. Berlin: Paul Cassirer and Hugo Helbing, 1929, 188, no. 108, Taf. 66.

Hackenbroch, Yvonne. “Italian Renaissance Bronzes in the Museum of Fine Arts at Houston.” American Connoisseur, June 1971, 124–25, fig. 4.

Jestaz, Bertrand. “Riccio et Ulocrino.” In Italian Plaquettes (Proceedings of the Symposium Italian Plaquettes, 1-22 March 1985), edited by Alison Luchs, 191–202. Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1989.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Catalogue of the Edith A. and Percy S. Straus Collection. Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1945, 37, no. 69.

Planiscig, Leo. Andrea Riccio. Vienna: H. Schroll, 1927.

Pope-Hennessy, John. Renaissance Bronzes from the Samuel H Kress Collection: Reliefs, Plaquettes, Statuettes, Utensils and Mortars. London: Phaidon for the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, 1965.

Vitry, Paul, Jean Guiffrey, and Gaston Migeon. La Collection de M. Gustave Dreyfus. Paris: Manzi, Joyant & Cie, 1908.

Wilson, Carolyn C. Italian Paintings, XIV–XVI Centuries, in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in association with Rice University Press and Merrell Holberton, 1996, 259–60, figs. 16–17.

ProvenanceEduard Simon (1864–1929), Berlin; [Dr. Eduard Simon sale, Cassirer and Helbing, Berlin, October 10, 1929, lot 108]; Dr. Simon Meller (1875–1949); acquired in January 1937 by Percy Straus from Meller; bequeathed to MFAH, 1944.Comparative Images

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has made every effort to contact all copyright holders for images and objects reproduced in this online catalogue. If proper acknowledgment has not been made, please contact the Museum.