God the Father

Antoine, Elisabeth. Art from the Court of Burgundy 1364–1419. Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 2004, 257–58, no. 97.

Barnet, Peter, ed. Images in Ivory: Precious Objects of the Gothic Age. Detroit: Detroit Institute of Arts in association with Princeton University Press, 1997, 45, no. 1.12.

Erlande-Brandenburg, Alain. L'art gothique. 2nd ed. Paris: Citadelles & Mazenzod, 2004, 473, fig. 688.

Gaborit-Chopin, Danielle. Elfenbeinkunst im Mittelalter. Fribourg: Berlin Mann, 1978, 173–174, Abb. 212; 214, no. 189.

Gothic Ivories Project at The Courtauld Institute of Art, London. Accessed September 17, 2018.

Jugie, Sophie. The Mourners. Tomb Sculptures from the Court of Burgundy. Dallas: FRAME/French/Regional/American Museum Exchange, 2010.

Koechlin, Raymond. Les Ivoires Gothiques Français. 3 vols. Paris: Auguste Picard, 1924.

Marzio, Peter. A Permanent Legacy: 150 Works from the Collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1989, 100–102.

Morand, Kathleen. Claus Sluter, Artist at the Court of Burgundy. London: H. Miller, 1991, 327, 329, fig. 57.

Mosneron-Dupin, Isabelle. “La Trinité debout en ivoire de Houston et Les Trinités bourguignonnes de Jean de Marville à Jean de la Huerta.” Wiener Jahrbuch für Kunstgeschichte 43 (1990): 35–65.

Mosneron-Dupin, Isabelle. “Le thème de la Trinité dans la sculpture à la Chartreuse de Champmol et en Bourgogne.” In Claus Sluter en Bourgogne. Mythe et représentations. Edited by Catherine Gras, 15–18. Dijon: Inventaire Général, 1990, 16.

Mosneron-Dupin, Isabelle. “Les Trinités en Bourgogne, de Jean de Marville à Jean de la Huerta. Réflexions sur l’usage des modèles dans les ateliers de sculpteurs bourguignons.” In Actes des Journées Internationales Claus Sluter (Septembre 1990), 193–209. Dijon: Association Claus Sluter, 1992, 198–200, 202–3, figs. 4–5.

Musée du Louvre. Paris, 1400: Les Arts sous Charles VI. Paris: Société Française de Promotion Artistique, 2004, 208–9, fig. 56.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Catalogue of the Edith A. and Percy S. Straus Collection. Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1945, 31, no. 57.

Prochno, Renate. Die Kartause von Champmol: Grablege der burgundischen Herzöge 1364-1477. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 2002, 69–70, Abb. 31.

Randall, Richard. Masterpieces of Ivory from the Walters Art Gallery. New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1985, 184, 188.

Randall, Richard. The Golden Age of Ivory: Gothic Carvings in North American Collections. New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1993, 21, pl. 5; 45–46, no. 26.

Verdier, Philippe. “La Trinité debout de Champmol.” In Etudes d’art francais offertes à Charles Sterling. Edited by Albert Châtelet and Nicole Reynaud, 65–90. Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 1975, 65–66.

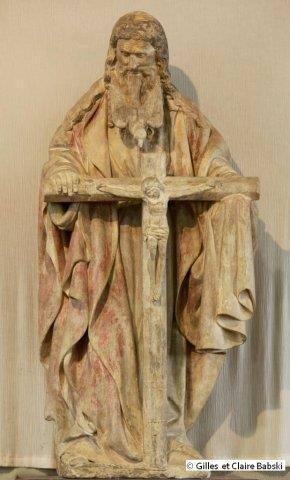

ProvenanceStated to be from Henry Garnier collection, Lyon, France; [Joseph Brummer Gallery, New York]; Percy S. Straus, January 1935; bequeathed to MFAH, 1944.This magnificent carving, among the most beautiful and perhaps the most emotionally profound of the sculptures in the Straus Collection, is a masterpiece of late medieval ivory sculpture. God the Father is shown as a bearded figure with long, flowing hair, who stands with his arms outstretched, his mouth open. His voluminous robe, belted at the waist and gathered up in his arms, cascades towards the ground in elaborate folds, echoing the locks of the hair and beard, and forming a sort of protective layer, seen especially well from the back, toward the left. The carving displays an almost incredible virtuosity, with paper-thin folds of robes hollowed into fantastical shapes, especially on the left, where the folds form caverns and the space under the right arm is deeply undercut. There is a large hole in the base, with a bayonet fitting.

The figure, a luxurious, even extravagant production, is carved from a single piece of what must have been a very large elephant tusk. It has suffered a certain amount of damage. In addition to the major loss of the right arm and hand, there is damage to the back of the head, where a section of ivory is missing,1 and a metal tube has been inserted. This tube, perhaps made of silver, may well be a later addition, perhaps for the insertion of a halo, presumably also in metal. There is considerable wear to the head and face. Other losses include part of the base at proper right and some of the ends of God the Father’s robe. The drapery of the statuette was repaired in 1972 by Marcel Gibrat, New York, after damage in an accident.

Although today it appears remarkably self-contained, the God the Father is in fact a fragment, the surviving portion of a group depicting the Trinity. God the Father would originally have held before him in his outstretched hands a cross with the figure of the crucified Christ; above the head of Christ would have hovered a dove, representing the Holy Spirit. The cross and the dove were probably carved as one piece. God’s open mouth today makes it seem as if he is speaking or crying out, enhancing the drama of the Straus figure. However, the mouth may in fact, more prosaically, have served for the insertion of a fixing tang projecting from the back of the dove. There is another such cavity in the left hand, which retains a fragment of its tang.

The Trinity is a Christian doctrine in which God is regarded as a single nature, one that is however composed of three persons, the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. Referred to in Saint Matthew’s Gospel (28:19), “Go ye therefore, and teach all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost,” the Trinity was subsequently expounded by Saint Augustine in his De Trinitate. From around the twelfth century the doctrine begins to appear in art in its characteristic form. Most depictions of the Trinity in Western art show God seated on a throne of grace, but exceptionally a small group of works, almost all of which were made in Burgundy, depict him standing. The Straus figure is the only ivory in this group and indeed the only surviving ivory carving that can be reliably associated with the Burgundian court workshops. It seems likely that sculptures in ivory were not just bought from Paris, but were also produced in Dijon; in 1377, the sculptor Jean de Marville, described as the Duke’s “carver of small works,” purchased from the Parisian tabletier (ivory turner) Jehan Girost twenty-six pounds of ivory for “tasks with which he was charged by Monseigneur.”

The small group of surviving representations of the Trinity with God the Father standing may all derive from what must once have been a famous monumental image of the subject, by Jean de Marville. In 1385 Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, founded in Dijon the Carthusian monastery of Champmol, which was to be specifically dedicated to the Trinity and to the Virgin Mary. In 1388 on the eve of the feast of the Trinity and of the day of celebration of the dedication of the new church of the Charterhouse, Jean de Marville delivered a statue of this subject to the church.2 Marville’s Trinity, which has long been lost, was probably placed behind the high altar, where it would have provided a visual symbol of the mystery of the Eucharist. It is likely with its base to have measured more than twelve feet (3.8 metres) in height, so would have towered over the altarpiece.3 We have no information on the appearance of Marville’s Trinity; the Charterhouse is known to have contained examples of the iconography with God the Father shown seated, as well as standing. It seems nevertheless on balance probable that Marville’s sculpture showed him standing and that it was the model for the surviving groups of this type. As well as the Straus figure, there are three examples in stone, the first given to the Chapel of the Holy Cross of Jerusalem in Dijon in 1459, the second also formerly in Dijon, but today in the church in Genlis (fig. 69.1), and a fragment in the Musée Archéologique in Dijon (fig. 69.2).4 All show God the Father standing, holding in both hands the Cross with the crucified Christ, whilst the Holy Spirit hovers above Christ’s head, partly obscuring God’s face. God the Father’s left hand is covered with the drapery of his robe, while the right hand is uncovered; the missing right hand in the Straus figure, which would have been carved together with the lost Cross, would undoubtedly also have been uncovered. We cannot though know if it would have supported the Cross from below, as in the Chapel of the Holy Cross group, or from above, as in the other two sculptures. The stone examples, in particular that in Genlis, also show God with long, flowing hair and wearing a heavy robe with many folds. A similar depiction of the Trinity on a smaller scale, which gives a good idea of how the Houston group might originally have looked, is the statuette depicted above the chimneypiece in Robert Campin’s painting of Saint Barbara of 1438, in the Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid (fig. 69.3).

Discussion of the Straus God the Father has largely focused on its dating. Is it a work from the late fourteenth century, when the great sculptor Claus Sluter (1340–1405) was working in Dijon, perhaps even, as suggested by Isobel Dupin, a product of the workshop of Jean de Marville, whom we know worked in ivory? Or does it date from the first decades of the next century, when a new generation of sculptors such as Claus de Werve (died 1439) and Juan de la Huerta (active c. 1410/20–after 1462) took up Sluter’s motifs in a quieter, less intense form?

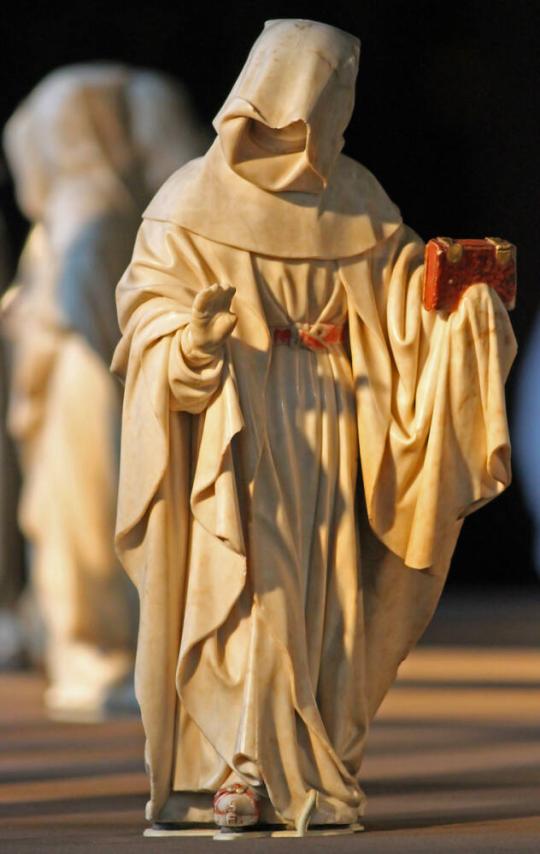

The dating is an exceedingly difficult question, since the Houston figure’s status as the only secure ivory carving from Burgundy means that meaningful stylistic comparisons are hardly possible. There are no surviving sculptures that can be securely attributed to Jean de Marville, other than his participation in the work on the tomb of Philip the Bold. If as is probable Marville’s Trinity, unveiled in 1388, was the model for the derivations, then it seems to have continued to have been influential over a period of several decades, until well into the fifteenth century. The vendor of the ivory Joseph Brummer noted, as early as 1935,5 the close parallels between the God the Father and one of the mourners from the tomb of John the Fearless and his wife (fig. 69.2), commissioned in 1443 from Juan de la Huerta and made by him and by Antoine Le Moiturier.6 Except for iconographical differences, notably the addition of a cowl for the mourning figure, the similarities are indeed striking. Although the contract for the tomb of John the Fearless specified that the monument should as far as possible imitate the earlier tomb of Philip the Bold, the model does not appear to have been a mourner on that tomb, but rather some version of the Trinity. The parallels even extend to the reverse of the two figures,7 suggesting that the sculptor of the mourning figure had access to an example of the Trinity that could be viewed in the round.

Although it may never be possible to resolve the problem of the precise dating of the statuette, this is secondary to its unquestioned status as a masterpiece of Burgundian court art and one of the finest medieval ivory figures to have survived.

—Jeremy Warren

Notes

1. It is possible this section was originally carved separately and adhered to the head, and has dropped out at some point. It might have been separately made to assist with the insertion of the metal tube. A small nick in the fringe of hair is in a line with the tube, so seems to be related with the latter in some way.

2. Philippe Verdier, “La Trinité debout de Champmol,” in Etudes d’art francais offertes à Charles Sterling, ed. Albert Châtelet and Nicole Reynaud (Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 1975), 66–67; Renate Prochno, Die Kartause von Champmol. Grablege der burgundischen Herzöge 1364-1477 (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 2002), 67–69.

3. Prochno, Die Kartause von Champmol, 68–69.

4. Verdier, “La Trinité debout de Champmol,” 71–72, figs. 51–52; Prochno, Die Kartause von Champmol, 69–70, 77, Abb. 32–34; Elisabeth Antoine, Art from the Court of Burgundy 1364-1419 (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 2004), 240, figs. 4–5, 243, no. 85.

5. Joseph Brummer to Edith A.Straus, January 24, 1935, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, archives.

6. Mourner no. 78. Isabelle Mosneron-Dupin, “La Trinité debout en ivoire de Houston et Les Trinités bourguignonnes de Jean de Marville à Jean de la Huerta,” Wiener Jahrbuch für Kunstgeschichte 43 (1990): 63–65, fig. 11; Sophie Jugie, The Mourners. Tomb Sculptures from the Court of Burgundy (Dallas: FRAME/French/Regional/American Museum Exchange, 2010), 112–13.

7. See Isabelle Mosneron-Dupin, “Les Trinités en Bourgogne, de Jean de Marville à Jean de la Huerta. Réflexions sur l’usage des modèles dans les ateliers de sculpteurs bourguignons,” in Actes des Journées Internationales Claus Sluter (Septembre 1990) (Dijon: Association Claus Sluter, 1992), figs. 4–7, for a useful set of photographic comparisons.

Comparative Images

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has made every effort to contact all copyright holders for images and objects reproduced in this online catalogue. If proper acknowledgment has not been made, please contact the Museum.