Virgin and Child

Frame (irregular): 55 5/8 × 22 1/2 in. (141.3 × 57.2 cm)

Arslan, Wart. “Una Madonna di Antonio Vivarini.” Revista d’arte 12 (1930): 543.

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932.

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works, with an Index of Places. London: Phaidon, 1957.

Berenson, Bernard, and Emilio Cecchi. Pitture italiane del Rinascimento: catalogo dei principali artisti e delle loro opere con un indice dei luoghi. Milan: U. Hoepli, 1936.

Coletti, Luigi. Pittura veneta del Quattrocento. Novarra: Istituto Geografico de Agostini, 1953.

Flanagan, Jack Key. “Report of the Conservator.” The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston: Bulletin of the Museum 17, no. 2 (1955): unpag., figs. 1–4.

Holgate, Ian Richard. “The Vivarini Workshop and Its Patrons.” PhD diss., University of Saint Andrews, Edinburgh, 1999.

Magliani, Stefania, In Pinacoteca Comunale di Città di Castello, vol. 1. Edited by Francesco Federico Mancini. Milan, 1987, 1989.

Marandel, J. Patrice. In The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston: a Guide to the Collection. Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1981.

Offner, Richard. “The Straus Collection Goes to Texas.” Art News 44, no. 7 (May 15–31, 1945): 14, cat. 16.

Pallucchini, Rodolfo. I Vivarini (Antonio, Bartolomeo, Alvise). Venice: Neri Pozza, 1962.

Perkins, F. Mason. “A Painting by Antonio Vivarini.” Art in America 16, no. 1 (December 1927): 12–16, repr. 13.

Robertson, Giles. Giovanni Bellini. Oxford: Clarendon, 1968.

Sulzberger, Suzanne. “Variation sur un thème iconographique: ‘La Vierge et l’Enfant a mi-corps,” Venezia e l’Europa, Atti del XVIII Congresso Internazionale di Storia dell’Arte. Venice, September 12–18, 1955 (Venice 1956): 231.

Steer, John. Alvise Vivarini: His Art and Influence. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Catalogue of the Edith A. and Percy S. Straus Collection Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1945.

Valentiner, Wilhelm Reinhold, and Alfred M. Frankfurter. “Guide and Picture Book: Official Souvenir, New York World’s Fair.” The Art News (1939).

Valentiner, Wilhelm Reinhold, and Alfred M. Frankfurter. Catalogue of European Paintings and Sculpture from 1300–1800: Guide and Picture Book. New York, 1939.

Van Marle, Rainmond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting, vol. 17. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1935.

Venturi, Lionello. Pitture italiane in America, vol. 2. Milan: Hoepli, 1931.

Venturi, Lionello. Italian Paintings in America, vol. 2. Milan: Hoepli, 1933.

Wilson, Carolyn C. Italian Paintings, XIV–XVI Centuries, in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in association with Rice University Press and Merrell Holberton, 1996.

Zeri, Federico. “Un ‘San Giorlamo’ firmato di Giovanni d’Alemagna.” Studie di storia dell’arte in onore di Antonio Morassi (Venice, 1971): 44–45, fig. 7.

In the catalogue of the Straus Collection produced in 1945 by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, this work is attributed to Antonio Vivarini. F. Mason Perkins, who was instrumental in Percy S. Straus’s acquisition of the panel in 1925, described it as “one of the most dignified and truly religious of all [Antonio’s] representations of the Madonna. . . . an image of singular impressiveness, as well as one of unusual spiritual and decorative charm.”1 The attribution has remained unquestioned, and Perkins’s assessment of its importance still pertains as well. Antonio Vivarini, born on the island of Murano—where his father worked in its famous glass manufacturing industry—forged a successful career as a painter in Venice. At the time of his earliest signed work, dating from 1440,2 he seems to have entered into a partnership with the older Giovanni d’Alemagna (1411–1450), and their workshop soon rivaled that of the Bellini family. Like the Bellinis, the Vivarini family also produced several well-known painters besides Antonio, including his brother Bartolomeo (active c. 1450–post 1491) and Antonio’s son Alvise (1476–1503/5).3 The great scholar of Italian Renaissance Roberto Longhi dubbed Antonio Vivarini the “Masolino of Venetian painting” because of his pivotal position between late Gothic and early Renaissance art.4 Most scholars date this panel around 1440, but Perkins believed this work to be a product of his maturity, without specifying an actual date.5

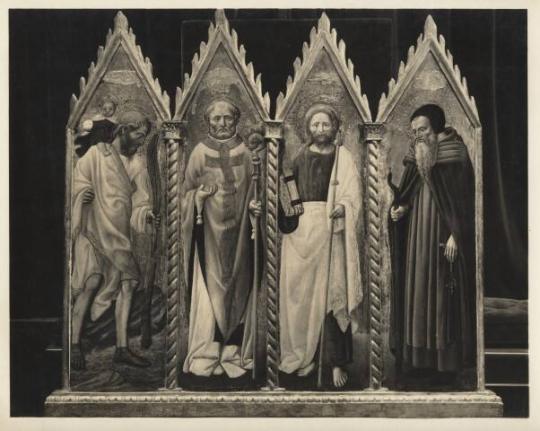

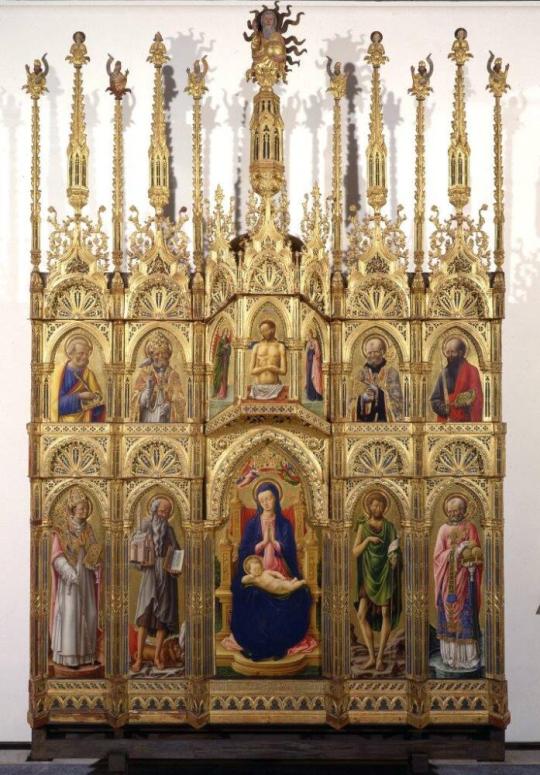

According to Federico Zeri, the Straus Vivarini was the central panel of an altarpiece whose lateral panels depicted Saints Christopher, Nicholas, James, and Anthony Abbot. The present whereabouts of these panels, formerly in the Coughlan collection, is unknown (fig. 11.1).6 Although probably painted ten years earlier, this altarpiece comprising the Houston Madonna and the four saints would have shared great similarities with that in Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna (fig. 11.2), which was painted by Antonio Vivarini together with his brother Bartolomeo around 1450.7 In both cases, the enthroned Virgin is shown in a strictly frontal pose as she adores the Christ Child recumbent across her lap. The Child’s nudity is understood to presage Christ’s sacrifice on the cross, also hinted at by the crossed ankles. It is an interesting combination of the imagery of the Nativity, where the Madonna often kneels in adoration, and the Pietà, where she holds the dead body of her son on her lap. Although Vivarini was probably not the inventor of this iconography, he popularized this type through frequent repetitions, which were in turn perpetuated by Bartolomeo and Alvise Vivarini. Here, the slight awkwardness of the Child’s pose, whose head and shoulders seem unsupported, points to Vivarini’ s early struggle with capturing three-dimensional figures within the framework of a restrictive, hierarchical arrangement. The gold ground with its incised flames is a vestige of the Gothic style, as is the throne itself with its scalloped base. By contrast, the deep folds of the Madonna’s magnificent red mantle highlight the plasticity of her form in a forward-looking manner. The stylized pomegranates that decorate the mantle are the Christian symbol of the Resurrection and of eternal life. Thus, Vivarini’s exquisite work expresses deep religious meaning in every aspect of its composition.

—Helga Kessler Aurisch

Notes

1. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Catalogue of the Edith A. and Percy S. Straus Collection (Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1945), 14, no. 16.

2. Ian Richard Holgate, “The Vivarini Workshop and Its Patrons” (PhD diss., University of Saint Andrews, Edinburgh, 1999), 38–39.

3. Rodolfo Pallucchini, I Vivarini (Antonio, Bartolomeo, Alvise) (Venice: Neri Pozza, 1961), introduction page, not numbered.

4. Carolyn C. Wilson, Italian Paintings, XIV–XVI Centuries, in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in association with Rice University Press and Merrell Holberton, 1996), 90.

5. F. Mason Perkins, “A Painting by Antonio Vivarini,” Art in America 16, no. 1 (December 1927): 12–16.

6. Holgate, “Vivarini Workshop,” 40.

7. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 196–97.

Comparative Images

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has made every effort to contact all copyright holders for images and objects reproduced in this online catalogue. If proper acknowledgment has not been made, please contact the Museum.