Virgin and Child

Frame: 39 1/4 × 23 3/16 in. (99.7 × 58.9 cm)

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932.

Berenson, Bernard, and Emilie Cecchi. Pitture italiane del Rinascimento: catologo dei principali artisti e delle loro opere con un indice dei luoghi. Milan: U. Hoepli, 1936.

Berenson, Bernard. The Italian Painters of the Renaissance, vols. 1, 2. London: Phaidon, 1968.

Bowron, Edgar Peters, and Mary G. Morton, Masterworks of European Painting in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press in association with the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2000.

Boskovits, Miklós, and Erich Schleier. Gemäldegalerie Berlin: Katalog der Gemälde; Frühe italienische Malerei. Berlin: Mann Verlag, 1988.

British Institute of Florence. “Hutton Collection.” Accessed August 20, 2019. www.britishinstitute.it/en/archive/the-archive/hutton-collection.

Bruschettini, Daniela. In Simone Martini e ‘chompagni.’ Siena: Pinacoteca Nazionale, 1985, 110, repr. Cristina De Benedictis in “Pittura e miniatura del Duecento e del Trecento in terra di Siena.” Pittura in Italia (1986): 325–63.

Caleca, Antonio. “Tre polittici di Lippo Memmi: Un ‘ipotesi sul Barna e la bottega di Simone di Lippo, 2.” Critica d’arte, n.s., 42, no. 151 (January–July 1977): 75, fig. 52.

Carli, Enzo. La Pittura senese. Milan: Electa, 1955.

Carli, Enzo. “Dipinti Senesi Nel Museo Houston.” Antichità viva 2, no. 4 (April 1963): 12, 15, 17, fig. 1.

Carli, Enzo. “Ancora dei Memmi a San Gimignano.” Paragone, n.s., 14, no. 159 (March 1963): 35, 43n12.

Carli, Enzo. La pittura senese del Trecento. Milan: Electa, 1981.

Davies, Martin. “Italian School.” In European Paintings in the Collection of the Worcester Art Museum. Worcester, MA: Worcester Art Museum, 1974.

De Benedictis, Cristina. “Naddo Ceccarelli.” Commentari, n.s., 25, nos. 3–4 (July–December 1974): 152, fig. 20.

De Benedictis, Cristina. “Il polittico della passione di Simone Martini e una proposta per Donato.” Antichità viva 15, no. 6 (November–December 1976): 4, 8, fig. 10.

De Benedictis, Cristina. La pittura senese 1330–1370. Florence: Salimbeni, 1979.

De Benedictis, Cristina. “Pittura e miniatura del Duecento e del Trecento in terra di Siena.” Pittura in Italia (1986): 325–63.

Edgell, George Harold. A History of Sienese Painting. New York: Dial, 1932.

Ercoli, Giuliano. “Nuovi studi sulla pittura senese del trecento: Un libro, una mostra e qualche riflessione.” Antichità viva 18, no. 4 (1979): 8.

Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1972.

Friedmann, Herbert. The Symbolic Goldfinch: Its History and Significance in European Devotional Art. Washington, D.C.: Pantheon Books for Bollingen Foundation, 1946.

Gabrielli, Anna Maria. “Ancora del Barna pittore delle storie del nuovo testamento nella collegiata di S. Gimingnano.” Bulletino senese di storia patria 7 (1936): 129.

Kanter, Laurence B. and Eric Zafran. Italian Paintings in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: 1, 13th–15th Century. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, distributed by Northeastern University Press, 1994.

Klesse, Brigitte. Seidenstoffe in der italienischen Malerei des 14. Jahrhunderts. Bern: Stämpfli, 1967.

Marginnis, Hayden, B. J. “The Literature of Sienese Trecento Painting 1945–1975.” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 40, no. 3–4 (1977): 287–89.

Maginnis, Hayden, B. J. The World of the Early Sienese Painter. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2001.

Martindale, Andrew. Simone Martini. Oxford: Phaidon, 1988.

Meiss, Millard. Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1951.

Meiss, Millard. “Nuovi dipinti e vecchi problemi.” Rivista d’arte, ser. 3:5, no. 30 (1955): 143.

Nygren, Olga Alice. Barna da Siena. Helsinki: Söderström, 1963.

Offner, Richard. “The Straus Collection Goes to Texas.” Art News 44, no. 7 (May 15–31, 1945): 16–23.

Pope-Hennessy, John. “Barna, The Pseudo-Barna and Giovanni d’Asciano.” Burlington Magazine 88, no. 515 (February 1946): 36–37.

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1970.

Shorr, Dorothy. The Christ Child in Devotional Images in Italy during the XIV Century. New York: George Wittenborn, 1954.

Schrader, Jack. In A Guide to the Collection. Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1981, 22, cat. no. 38.

Steinhoff, Judith. Sienese Painting after the Black Death. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Sutton, Denys. ”Robert Langton Douglas, III.” Apollo, n.s., 109, no. 208 (June 1979): 190–91.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Catalogue of the Edith A. and Percy S. Straus Collection Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1945.

Toritti, Piero. La Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena: I dipinti dal XII al XV secolo. Genoa: Sagep, 1980.

Van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting, vol. 2. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1924.

Van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting, vol. 5. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1925.

Van Marle, Raimond. “Unknown Paintings by Simone Martini and His Followers—I.” Apollo 4, no. 22 (October 1926): 163.

Van Os, Hendrik Willem. Marias Demut und Verherrlichung in der Sienesischen Malerei 1300–1450. s-Gravenhage (The Hague): Ministerie van Cultuur, Recreatie en Maatschappelijk Werk, 1969.

Ventroni, Sebastiana Delogu. Barna da Siena. Pisa: Giardini, 1972.

Venturi, Lionello. Pitture Italiane in America. Milan: U. Hoepli, 1931.

Venturi, Lionello. Italian Paintings in America. New York: E. Weyhe, 1933.

Volpe, Carlo. “Precisazioni sul ‘Barna’ e sul ‘Maestro di Palazzo Venezia.’” Arte antica e moderna 10 (1960): 152, 157, n. 14.

Weigelt, Curt. “Minor Simonesque Masters.” Apollo 14, no. 79 (July 1931): 9, fig. IX, 11.

Wilson, Carolyn C. Italian Paintings, XIV–XVI Centuries, in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in association with Rice University Press and Merrell Holberton, 1996.

ProvenancePrivate collection, Scotland, as "Byzantine Madonna;" [Captain R. Langton Douglas, London] [1]; acquired by Edith A. and Percy C. Straus, 1923; bequeathed to MFAH, 1944.[1] R. Langton Douglas was an art historian and the director of the National Gallery of Ireland, 1916–1923.

Most scholars agree that this superb depiction of the Madonna and Child is from the hands of a Sienese painter active around the middle of the Trecento, but pinpointing a specific master has remained controversial. Percy S. Straus acquired this work from his dealer R. Langton Douglas as a painting by Simone Martini. Douglas never expressed his thoughts publicly, but he repeated his confidence in the attribution in several letters to Mr. Straus. On January 23, 1923, he wrote, “‘The Madonna and Child’ of the Sienese School that you have recently bought from me is, in my opinion, undoubtedly a work of Simone Martini, painted by him at the same time as the ‘Madonna and Child’ . . . which is now in the Borghese Gallery in Rome. . . . It also recalls the Madonna in the ‘Annunciation’ in the Uffizi Gallery.”1 He thereby placed this work in the immediate proximity of Martini’s well-known masterworks. Since Douglas was a recognized authority on Sienese painting, Percy Straus must have felt assured of the validity of this attribution.2 However, it was called into question during the subsequent decades. Multiple and divergent suggestions have been put forward by many of the outstanding experts in the field, as laid out in detail by Carolyn C. Wilson.3 Some, including Adolfo Venturi and Raimond van Marle, have suggested that the painter was Simone Martini’s brother Donato, but Bernard Berenson thought the work to have been painted by Lippo Memmi, Simone Martini’s brother-in-law. Others, like Lionello Venturi and Richard Offner, have seen him as a follower of Barna da Siena, a painter whose very existence is questioned by a number of scholars.4 The pseudonym “Master of the Sienese Straus Madonna” was first coined by Curt Weigelt in 1931. Richard Offner, whose opinion Percy Straus valued greatly, assigned the work in 1945 to the “School of Barna,” but in the catalogue published in April of that year by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, it is listed as “School of Simone Martini,”5 reflecting the ongoing debate at the time the Straus Collection entered the museum. In 1974, Cristina De Benedictis, who agreed with the earlier findings of Weigelt, resurrected the pseudonym, which continues to be widely accepted, although not undisputed.

The controversy of the authorship, however, cannot overshadow the extraordinary quality of the work, which is indisputable. Its wonderful state of preservation allows a close reading of the image. The figures are characterized by the nobility of their expression, the elegance of their forms, and the exquisite detailing of their garments. The Virgin’s long oval face is distinguished by a long straight nose, a small and delicate mouth, and pronounced almond-shaped brown eyes, whose gaze is focused on the Child. Her golden-orange hair is just visible beneath her dark blue mantle, which falls in simple folds around her spare form. Its gold embroidered border has become obscured, remaining barely visible, as has the golden star on her proper right shoulder. Beautifully preserved, on the other hand, is the delicate patterning of her dress in white and gold floral motifs rendered in sgraffito. This technique is also found on the gold and red cloth wrapped around the Child, seated in the crook of the Virgin’s left arm. The Child has curly hair of the same color as his mother, but his round face and round eyes are quite distinct from hers. Looking up to her with his mouth open, he clutches a goldfinch in his left hand, while raising his right. This gesture has been interpreted as playfully interacting with the bird or as a benediction. The motif of the goldfinch, which is central to this composition, was popular throughout the fourteenth century. It was thought to symbolize the passion of Christ, the resurrection, and the soul, but was also seen as a protection against disease, especially the plague.6 The Child’s energetic hand gestures and kicking legs are countered by the mother’s restraining hands and pensive expression. Thus, the sense of calm that emanates from the Virgin is conveyed through the use of the delimited contour of the figures, while their lively psychological interaction is expressed by the crisscrossing of the mother’s hands and the child’s legs. Their holiness is symbolized by the beautifully worked halos that encircle their heads and is emphasized by the gold ground, which represents the heavenly sphere in which they exist.

The gold ground ends in an arch above the figures that springs from three-dimensional gilded corbels. The ribs of the arch are also three-dimensional, probably built-up gesso that was then gilded. The spandrels between the outer and inner trefoil-shaped arch are decorated with floral punchwork, echoing that of the halos. Unfortunately, the original decorations of the spandrels between the arch and the upper edge of the frame have largely been lost and have been retouched. However, the overall quality of the painting is so remarkable that it can serve as a textbook example of the techniques put forth by Cennino Cennini (c. 1370–1440) in his treatise Il Libro dell’arte (The Craftsman’s Handbook), written in the 1390s for painters working in tempera, a mixture of pigments and egg yolk. Cennini advises placing a layer of green (terre verte) under the pink skin tones in order to make them seem more natural. Since it is difficult to achieve shading with tempera, darker layers overlaid by the same paint mixed with white and applied in very small strokes are used to create a sense of modeling. This technique, as well as the defining of the features with dark outlines, is easily discernable on this panel.7 It is also noticeable that this master followed Cennini’s instruction concerning the handling of the gold ground. Clearly, the outline of the figural group was drawn onto the red bole ground, then the gold leaf applied, and finally the figures painted in. This technique left no margin for error, since any changes to the incised outlines of the figure would remain visible, as is the case here at the Virgin’s right elbow. The sgrafitto technique used to create the brocade fabrics was achieved by overpainting the gold ground with a layer of color and scratching the pattern out with a sharp tool. A similar love of refined decoration is found in the halos, which have been carefully embellished with intricate punchwork.

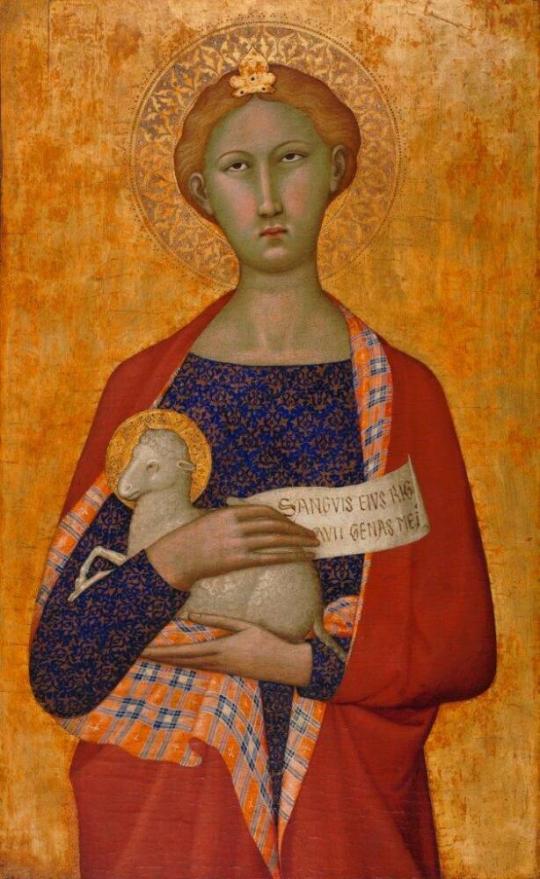

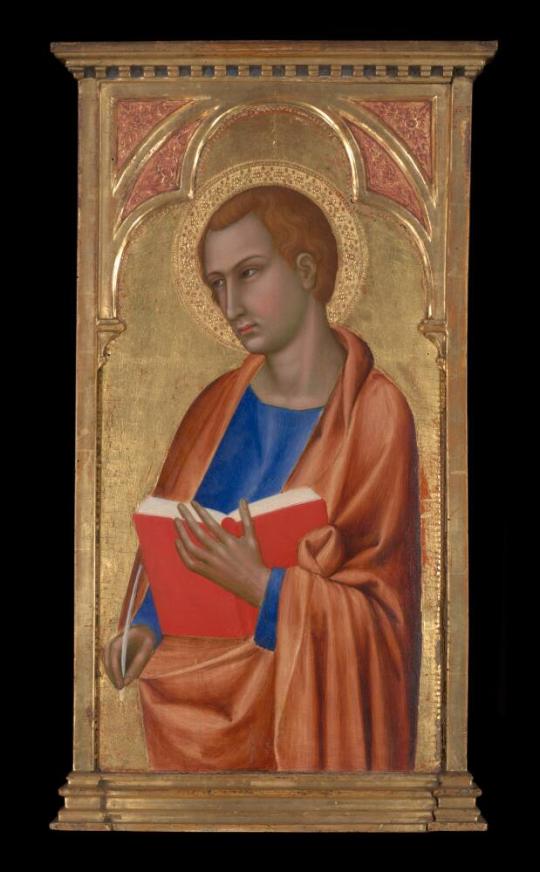

As noted by Carolyn Wilson, Edgar Peters Bowron, and Mary Morton, the painting was originally the central panel of a large altarpiece. The images of Saint Agnes (fig. 1.1) preserved at the Worcester Museum of Art, and Saint John the Evangelist, today in the Yale University Art Gallery (fig. 1.2), are seen by numerous scholars as very likely to have been lateral panels surrounding the Madonna and Child. The similarities of the facial features, the three-quarter length of the figures, and the insistence on luxurious textiles all point to their similar origin and the definite possibility of having been part of the same altarpiece.8 The Saint John the Evangelist panel shows not only great stylistic similarities, but also has the same raised architectural elements as the Straus panel. Although they are modern reconstructions, they follow previous states of the panel, as visible in x-ray examinations,9 and strongly indicate a common origin. This panel was part of the Hutton Collection, assembled by the travel writer Edward Hutton, who had owned up to eleven works by Simone Martini, to whom this work was likely attributed.10 The Saint Agnes panel, on the other hand, was sold by R. Langton Douglas in the same year he sold the present work to Percy Straus, a circumstance that is highly suggestive of the same origin. Unfortunately, this panel has been restored several times, and the gold background, which does not have any three-dimensional architectural elements, is modern.11 There are further inconsistencies among the three panels, including the dimensions. The Saint Agnes panel, at 28 1/2 x 17 3/4 inches, is slightly smaller than the other two, and the Saint John the Evangelist panel, measuring 28 1/8 x 15 5/8 inches, is smaller than the present panel, which measures 31 1/8 x 17 1/2 inches. However, the discrepancies in size may be due to later reductions because of damage and do not necessarily preclude that the panels were originally assembled into one altarpiece, which furthermore was probably surmounted by an upper tier of smaller paintings. In fact, the small triangular panel with the image of a Bishop Saint, part of the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (fig. 1.3) may have been part of this superstructure. As Wilson points out, the motif of the bishop’s garments closely resembles the patterns found on cloth wrapped around the Child.12 To date, the uncertainty about the attributions continues. The larger panels are attributed to the Master of the Straus Madonna (rather than the Master of the Sienese Straus Madonna) by their respective repositories, but this may reflect an erroneous understanding of the two eponymous painters. On the other hand, the Bishop Saint is classified by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, as from the hand of the Master of the Sienese Straus Madonna.

In view of the recent discovery of the likely identity of the Master of the Straus Madonna as Ambrogio di Baldese (see cat. 8), it would seem desirable to take a fresh look at the problematic and inconclusive findings regarding his Sienese forerunner. However, despite its exquisite quality, this painting has to date not been given the attention in recent publications as the work of the Master of the Straus Madonna, and no conclusions regarding the painter’s identity have been put forth.13 This lack of new information is, of course, to be regretted, but it does speak of the enormous wealth of talent that existed in Siena in the middle of the fourteenth century, where the master painters’ workshops were filled with very gifted assistants and followers. Despite the ravages wreaked by the Black Death in the city as a whole and among the artistic community, they produced such a quantity of remarkable works that a master of this quality has so far remained anonymous.

—Helga Kessler Aurisch

Notes

1. R. Langton Douglas to Percy S. Straus, 1923, the Edith A. and Percy S. Straus Collection, MS 15, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, archives.

2. R. Langton Douglas had published several important works on Sienese Renaissance art, including A. Crowe and G. B. Cavalcaselle, edited by Langton Douglas, A History of Painting in Italy: Umbria, Florence and Siena from the Second to the Sixteenth Century (New York: C. Scribner, 1903-14), History of Siena (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1902), and Illustrated Catalogue of Pictures of Siena and Objects of Art (London: Burlington Fine Arts Club, 1904).

3. Carolyn C. Wilson, Italian Paintings, XIV–XVI Centuries, in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in association with Rice University Press and Merrell Holberton, 1996), 32–34.

4. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 33.

5. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Catalogue of the Edith A. and Percy S. Straus Collection (Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1945), 9.

6. Herbert Friedmann, The Symbolic Goldfinch (Washington, D.C.: The Bollingen Foundation, 1946), 10.

7. Edgar Peters Bowron and Mary G. Morton, Masterworks of European Painting in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press in association with the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2000), 2.

8. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 29, 32, and Bowron and Morton, Masterworks of European Painting, 2.

9. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 32; Yale University Art Gallery, Master of the Straus Madonna, Saint John the Evangelist, inv. no. 1946.12, accessed August 20, 2019, artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/48071.

10. British Institute of Florence, “Hutton Collection,” accessed August 20, 2019, www.britishinstitute.it/en/archive/the-archive/hutton-collection.

11. Worcester Art Museum,“Saint Agnes,” inv. no. 1923.35, accessed August 20, 2019, worcester.emuseum.com/objects/22698/saint-agnes.

12. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 32.

13. Hayden Maginnis, The World of the Early Sienese Painter (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2001), and Judith Steinhoff, Sienese Painting after the Black Death (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Comparative Images

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has made every effort to contact all copyright holders for images and objects reproduced in this online catalogue. If proper acknowledgment has not been made, please contact the Museum.