As in many cases of works from the incredibly productive period of the later fourteenth century in Florence, it has been difficult to settle the question of attribution of this small panel. It came on the art market in 1922 as a work by an anonymous Florentine painter from around 1360.1 Subsequently, Raimond van Marle attributed it to Jacopo di Cione in 1924,2 although Edward Hutton sold it to Percy S. Straus in 1927 as a work by Agnolo Gaddi. Carolyn C. Wilson points out that Bernard Berenson listed it as a work by Cione,3 yet he referred to it as “Gaddesque” in a letter to Percy Straus in 1930, and it was published as by Gaddi in the catalogue of the Straus Collection by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in 1945.4 Richard Offner, who had rejected the attribution to Gaddi in 1926, argued that the artist must have been associated with the workshop of Andrea di Cione (known as Orcagna) and his younger brother Jacopo.5 Offner, who became Percy Straus’s closest adviser on Italian painting, named this anonymous painter the Master of the Golden Gate after this painting. However this eponym did not come into use until 1976, a decade after Offner’s death.6 Despite the scholarly dispute regarding the attribution, there has been no doubt about its function as part of a predella (base) of an altarpiece. Sadly, the altarpiece can no longer be identified. Two other panels, The Adoration of the Magi (fig. 6.1), today in the Fogg Museum / Harvard Art Museums, and Nativity with Shepherds, formerly in the Western European Museum in Kiev but now lost, are so close in style that it is assumed they were part of the same predella.7 The Fogg painting was published as having been painted by the “Master of the Golden Gate,” but is now attributed to the Master of the Ashmolean Predella, whose name is derived from yet another small panel depicting the Birth of the Virgin, in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.8 Despite its stylistic and thematic similarities, its octagonal shape precludes it from having been part of the same predella as the Straus and Fogg panels.

The similarities of the Straus Collection work and the painting in the Fogg Museum are indeed striking. The compositions of both panels consist of a relatively shallow foreground in which the figures stand, with stark mountains in the background at right and an architectural element at left. The schematic handling of the rock surfaces are identical in both works, as are the single trees jutting abruptly from the sides of the mountains. Quite close in handling are the delicately brushed clumps of grasses that are richly strewn across the foreground and up the mountains in both paintings. The architectural elements, however, vary greatly. The rounded openings and plain walls of the crenelated city gate that plays such a major role in the meeting of Joachim and Anna is of an entirely different character from the Virgin’s Gothic throne with its pointed roof, spiked finials, and trefoil arches in the Adoration panel. However, in both cases the artist is obviously struggling with perspective as well as scale: the concept of linear perspective is not entirely understood, and the figures overpower the architecture. The treatment of the figures, the faces, hands, and costumes, points to the same artist, as does the choice of lively colors and the handling of details. Even the non-painterly elements, such as the punchwork of the halos and the decorative border framing the panels, are practically identical. So close, in fact, are the panels that Edgar Peters Bowron has ascribed them to one and the same artist.9

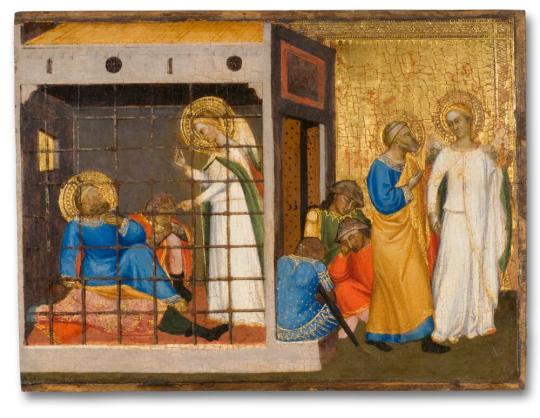

The theme of the predella from which these panels originate was most likely the life of the Virgin, based on the Golden Legend, a popular compilation of the lives of the saints by Jacobus da Voragine, published around 1260.10 The meeting of Joachim and Anna occurs at the beginning of that legend. This scene, so tenderly depicted in the Straus panel, captures the moment of the immaculate conception of the child that would be the Virgin Mary. Joachim, whose offerings had been rejected in the temple because his childlessness was considered a curse, isolated himself for some time among simple shepherds. An angel appeared to him, telling him that his wife would conceive and to meet her at the Golden Gate. The already elderly and until then woefully barren Anna, too, had a divine apparition and hastened to meet her husband. The miracle takes place when they embrace, here guided by the Archangel Gabriel, who touches both their heads. This event, not told in the Bible but originating in the Protoevangelium of James, was a particularly popular theme in fourteenth-century Italian painting. Giotto had painted the scene as part of the groundbreaking decoration of the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, completed in 1305. Although much of the incidental vocabulary of the scene remains constant over the course of the century—the shepherds, the female attendants, and, of course, the prominently featured gate—Joachim and Anna’s actions are depicted quite differently. In Giotto’s fresco, they are not just embracing tenderly but kissing fervently. This behavior was apparently found unsuitable for the depiction of such an aged couple a few decades later. Around 1330, Taddeo Gaddi, known as Giotto’s most gifted pupil and follower, depicted this scene for the Baroncelli Chapel in the Basilica di Santa Croce in Florence in a more reticent and seemly fashion. As in the Straus panel, Joachim and Anna are merely stretching their arms out to one another. Despite these superficial similarities, the Master of the Golden Gate is stylistically closer to Orcagna and even more so to his younger brother Jacopo di Cione than to either Taddeo or Agnolo Gaddi, as mentioned above.

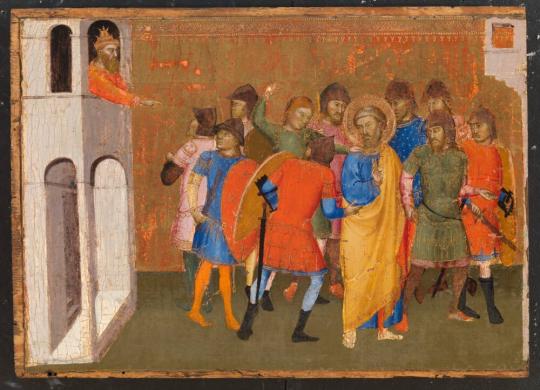

Only a few works are securely attributed to Jacopo di Cione, but it is generally accepted that he completed the panel of Saint Matthew (1369; Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence), which his older brother Orcagna had left unfinished at his death in 1368.11 The attribution of the Straus panel to an artist from Jacopo’s circle rests on two predella panels from his most important surviving altarpiece, The Coronation of the Virgin with Music-Making Angels and Saints (1370–71; National Gallery, London) that depict the life of Saint Peter. Today in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art (fig. 6.2) and the Rhode Island School of Design Museum (fig. 6.3), respectively, these panels reveal a treatment of the architectural elements and their relationship to the figures that is very similar to the Straus panel. The figures’ refined yet expressive gestures also correspond very closely, as does the lively use of color. A close comparison of these works makes it evident that Offner’s attribution is correct and that the Master of the Golden Gate was most likely a collaborator or follower of Jacopo di Cione during the last decades of the fourteenth century.

—Helga Kessler Aurisch

Notes

1. Catalogue de la Collection Chillingworth, Tableaux Anciens, XIIIe–XVIIIe Siècles, September 5, 1922, Lucerne, lot 100, p. 35, ill.

2. Carolyn C. Wilson, Italian Paintings, XIV–XVI Centuries, in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in association with Rice University Press and Merrell Holberton, 1996), 93.

3. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 92.

4. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Catalogue of the Edith A. and Percy S. Straus Collection (Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1945), cat. 11, 11–12.

5. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 92.

6. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 93.

7. Bowron and Morton refer to an untraceable Nativity with Shepherds, formerly in the Western European Museum, Kiev, having also formed part of this predella; see Edgar Peters Bowron and Mary G. Morton, Masterworks of European Painting in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (Princeton: Princeton University Press in association with the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2000), 6.

8. Bowron and Morton, Masterworks of European Painting, 6.

9. Bowron and Morton, Masterworks of European Painting, 6.

10. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 96, and Bowron and Morton, Masterworks of European Painting, 6.

11. Richard Fremantle, Florentine Gothic Painters from Giotto to Masaccio: A Guide to Painting in and near Florence, 1300 to 1450 (London: Martin Secker and Warburg, 1975), 161.

The Meeting of Anna and Joachim at the Golden Gate

Frame: 15 1/16 × 16 13/16 in. (38.3 × 42.7 cm)

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1932.

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: Florentine School: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works, with an Index of Places. London: Phaidon Press, 1963.

Berenson, Bernard, and Emilio Cecchi. Pitture italiane del Rinascimento: catalogo dei principali artisti e delle loro opere con un indice dei luoghi. Milan: U. Hoepli, 1936.

Boskovits, Miklós. Pittura fiorentina : alla vigilia del Rinascimento: 1370–1400. Florence: Edam, 1975.

Bowron, Edgar Peters. European Paintings before 1900 in the Fogg Art Museum: A Summary Catalogue Including Paintings in the Busch-Reisinger Museum. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Art Museums, 1990.

Bowron, Edgar Peters, and Mary G. Morton. Masterworks of European Painting in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press in association with the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2000.

Catalogue de la Collection Chillingworth, Tableaux anciens, XIIIͤ –XVIIIͤ siècles. Lucerne: Galeries Fischer, 5 September 1922, 35, cat. no. 100.

Exhibition of Paintings from Five U.S. Museums at the Hermitage State Museum, Leningrad; the Pushkin Museum, Moscow; the State Ukranian Museum, Kiev; the State Art Museum of Belorussian SSR, Minsk, and the Musée Marmotton, Paris, 1976.

Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1972.

Fremantle, Richard. Florentine Gothic Painters from Giotto to Masaccio: A Guide to Painting in and near Florence, 1300 to 1450. London: Martin Secker and Warburg, 1975.

Kanter, Laurence B., et al. Painting and Illumination in Early Renaissance Florence: 1300–1450. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1994.

Lloyd, Christopher. A Catalogue of the Earlier Italian Paintings in the Ashmolean Museum. Oxford: Clarendon, 1977.

Meiss, Millard. Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1951.

Offner, Richard. “The Straus Collection Goes to Texas.” Art News 44, no. 7 (May 15–31, 1945): 16–23.

Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: Supplement, A Legacy of Attributions, edited by Hayden B.J. Maginnis. New York: New York University, Institute of Fine Arts, 1981.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Catalogue of the Edith A. and Percy S. Straus Collection. Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1945.

Strehlke, Carl Brandon. Italian Paintings 1250–1450, in the John G. Johnson Collection and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art in association with the Pennsylvania State University Press, 2004.

Van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting, vol. 3. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1924.

Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford. An Exhibition of Italian Panels and Manuscripts from the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries in Honor of Richard Offner. Hartford, CT: Wadsworth Atheneum, 1965.

Wilson, Carolyn C. Italian Paintings, XIV–XVI Centuries, in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in association with Rice University Press and Merrell Holberton, 1996.

ProvenanceCollection Rudolph Chillingworth, Lucerne; Kaufmann, Munich; [Edward Hutton, London, 1926]; acquired by Percy S. Straus, New York, in 1927; bequeathed to MFAH, November, 1944.Comparative Images

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has made every effort to contact all copyright holders for images and objects reproduced in this online catalogue. If proper acknowledgment has not been made, please contact the Museum.