Virgin and Child

Frame: 44 15/16 × 32 9/16 in. (114.1 × 82.7cm)

Bätschmann, Oskar. Giovanni Bellini. London: Reaktion Books, 2008.

B[urroughs], B[ryson]. “Loan Exhibition of the Arts of the Italian Renaissance.” Bulletin of the Metropolitan Museum of Art 18, no. 5 (May 1923):110.

B[urroughs], B[ryson]. “Landscape in Italy in the Fifteenth Century.” Bulletin of the Metropolitan Museum of Art 18, no. 8 (August 1923): 200, repr. 198.

Christiansen, Keith. Giovanni Bellini and the Art of Devotion. Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2004.

Dussler, Luitpold. Giovanni Bellini. Frankfurt: Prestel, 1935.

Friedmann, Herbert. The Symbolic Goldfinch: Its History and Significance in European Devotional Art. Washington, DC: Pantheon Books for Bollingen Foundation, 1946.

Gamba, Carlo, Giovanni Bellini. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1937.

Ghiotto, Renato, and Terisio Pignatti. L’opera completa di Giovanni Bellini. Milan: Rizzoli, 1969.

Goffen, Rona. Giovanni Bellini. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1989.

Gronau, Georg. Giovanni Bellini: Des Meisters Gemälde in 207 Abbildungen. Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1930.

Heinemann, Fritz. Giovanni Bellini e i belliniani. Venice: Neri Pozza, 1962.

Heinemann, Fritz. Giovanni Bellini e i belliniani, III, supplemento e ampliamenti. Hildesheim, Zurich, New York: Olms, 1991.

“Maria mit dem Kind, Giovanni Bellini,” Gemäldegalerie der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin - Preußischer Kulturbesitz, inv. 10A, id.smb.museum/object/863126.

Poore, Dudley. “Italian Renaissance Exhibition.” The Arts III: 5 (June 1923): 410, repr. 406.

Tempestini, Anchise. Giovanni Bellini. Paris: Gallimard, 2000.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Catalogue of the Edith A. and Percy S. Straus Collection. Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1945.

Van Marle, Raimond. “Representation of Great Italian Masters in American Collections Very Inferior to That of Other School.” Art News 28, no. 22 (Mar. 1, 1930): 21.

Van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting , vol. 17. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1935.

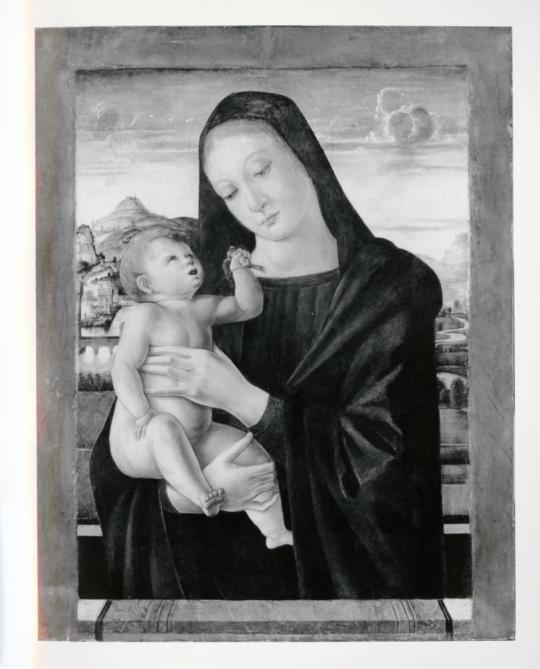

ProvenancePrivate Collection, Bologna (?); Alverà, Venice; Edith A. and Percy S. Straus Collection, New York, 1922-1945; given to MFAH, 1944.The great Venetian Renaissance painter Giovanni Bellini, born into an extensive and highly influential family of painters and known particularly for his exceptionally beautiful altarpieces such as the Frari triptych or the San Zaccaria altarpiece, did not emerge as a recognizable talent until relatively late in life. He trained in the workshop of his father, Jacopo, together with his half-brother Gentile and brother-in-law Andrea Mantegna. The first documented work entirely from Giovanni’s brush, the Pesaro altarpiece, is dated 1470, when he was already forty.1 Yet it is believed that he started to paint works for private devotion around 1460, filling a demand by Venice’s rising middle class.2 More than one-third of Bellini’s surviving output consists of half-length paintings of the Virgin and Child (alternately referred to as Madonna and Child) such as the present work.3 Moreover, Bellini is the artist most closely associated with this image type, which he not only treated with astonishing inventiveness, but which, according to Rona Goffen, he also permeated with a deep feeling of religious conviction.4

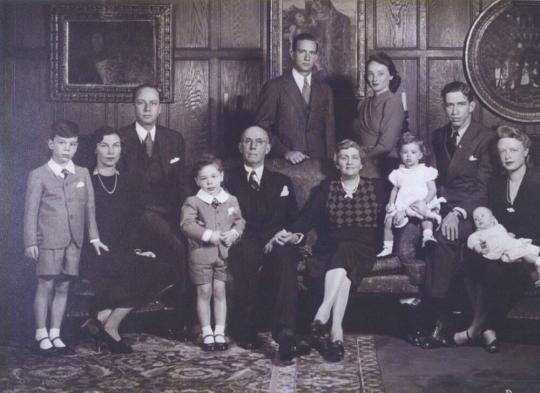

Percy S. Straus acquired this work through F. Mason Perkins from the Alvera collection, Bologna, in 1922. Straus sought the expertise of various scholars, as documented by letters now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, archives.5 Sadly, what must have been a prized possession (fig. 14.1) had sustained serious damage at an undetermined time. Parts of the Virgin’s face, her third and fourth finger, and large swaths of her mantle and dress, as well as the Christ Child’s left leg, had been lost due to insect tunnels.6 In the earliest photographs, dating from 1925, 1930, and 1931, the painting already appears heavily restored, probably by a nineteenth-century restorer. Nine years after its acquisition by Straus, Marcel J. Rougeron was commissioned to restore it again, but no conservation records have survived. The first conservation record dates from 1954, when Jack Flanagan treated the painting, removing most of the earlier restorations, especially in the Virgin’s mantle and dress, but leaving the nineteenth-century restoration of the face as it was.

In 1970, Gabriele Kopelman removed all earlier restorations and repainted the face in a manner that was never deemed very successful (fig. 14.2). The most recent campaign, undertaken by the Museum’s painting conservator Maite Leal, once more removed all earlier overpainting, which again included most of the Madonna’s mantle and dress. Leal restored the face, following the still visible underdrawing of the features. She also repainted the veil, whose existence was also still indicated by faint outlines. Interestingly, the figure of the Child had suffered the least over the course of the centuries. It was left mostly intact and required only a toning down of the underdrawing, which had become more visible over the centuries.7

The losses to the figures were evident at the time of Straus’s acquisition, but the remarkably beautiful and skillfully painted landscape background convinced many scholars of its authenticity. Indeed, Giovanni Bellini is credited with the innovation of placing the Madonna and Child in front of a landscape, and this feature speaks very much in favor of this painting having come from his brush. Yet the ensuing debate around its authenticity continued for decades, with a majority of art historians accepting the attribution to Bellini.8 Unfortunately, the various restorations, mentioned above, altered the appearance of the figures significantly, a fate this work shares with many other Madonna and Child panels by Bellini.9 Carolyn C. Wilson, who analyzed the painting thoroughly in her 1996 publication on the Italian paintings in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, left the door slightly ajar concerning the question of attribution, by assigning it to either Giovanni Bellini or a fifteenth-century Venetian follower.10 More recently, Anchise Tempestini, who judged the work on the basis of the restoration of 1970, attributed the work to the studio of Jacopo Bellini in his catalogue raisonné, published in 2000.11

Since, according to the latest findings, 46 percent of the original surface has been lost, it is extremely difficult to arrive at a definite and indisputable attribution. A close comparison with Bellini’s accepted works of this genre, however, can been revealing. Keith Christiansen, in his 2004 study of Bellini’s devotional paintings, points out that until 1479, when his brother Gentile left Venice for Constantinople, Giovanni had “worked almost exclusively as a painter of altarpieces and devotional images.”12 Thirty half-length images of the Madonna and Child are firmly ascribed to Bellini, but this number is increased to about eighty when taking into consideration the works deemed to have been produced by his workshop.13 Bellini and his assistants were able to accomplish this large number of images through the use of cartoons and other mechanical aids that allowed them to repeat the salient parts of a composition. Thus, two and sometimes three images clearly stem from one original, but are varied in their details, such as the Child’s stance, his garment, the position of the Madonna’s hands, the background, and the addition of saints and donors.14 In a few instances, telltale signs of pouncing or tracing are still extant beneath the paint layer, but none have been discovered on the Straus painting, despite investigation by X-ray and infrared reflectography.

The Straus panel is considered to be closely related to a work in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin, dated 1460–65 (fig. 14.3). This painting, firmly attributed to Bellini, is one of the earliest instances where he included a landscape and a naturalistic sky as background for the sacred figures, an important element that also distinguishes the Straus panel. Oskar Bätschmann has called this innovation Bellini’s most significant contribution to the images of the Virgin and Child.15 In both paintings, as in virtually all his paintings of the Madonna and Child, the Madonna is seen in half-length, the common size for Renaissance portraits, thus implying that the image of the Virgin is a portrait.16 She is usually seen behind a stone parapet at the picture’s edge on which the Child eithers sits or stands. This parapet not only separates the viewer from the sacred figures but also acts as a symbol of Christ’s tomb and his Passion at which Mary is present, and as a symbol of an altar on which the Eucharist is celebrated. By implication, the figures are apparitions that inhabit neither the viewer’s space nor the landscape, but are united with it through the light with which Bellini suffuses the entire picture space.17 The tender interaction between the figures, the Child gazing into his mother’s face while she inclines her head toward him, is an important element shared by the Berlin and Straus panels. The landscapes of both the Berlin and Straus paintings are painted on a smaller scale than the figures and share a number of elements, such as a river, a winding road, a mountainous outcropping, and buildings, but by comparison, the Straus landscape is even more finely rendered, particularly in the closely observed reflection of the bridge over the river.

There are important differences in the treatment and arrangement of the figures between the Straus and Berlin panels, particularly in regard to the Child. Instead of standing, as in the Berlin panel, he is sitting in the Straus panel with splayed legs on his mother’s right arm, his own right arm extended, while clutching a goldfinch in his left hand. Although Bellini often made use of symbolic attributes such as an apple, a pear, or a book, none of his other images of the Madonna and Child include a goldfinch, a bird traditionally associated with Christ’s Passion and often seen in Italian painting from the 1430s onward.18 Notably, the Child of the Straus panel is shown in the nude, while in the Berlin panel he is dressed in a tunic, a garment commonly found in earlier Byzantine and pre-Renaissance paintings. In virtually all of his later paintings, Bellini depicts the Child nude, reflecting a new theological emphasis on Christ’s incarnation, as a being both divine and human.

While the Berlin Madonna and Child of 1460–65 shares many similarities with the Straus panel, various scholars have considered the latter to be even closer to the painting from Santa Maria dell’Orto (fig. 14.4).19 Sadly, this painting was stolen in 1993 and is still missing, but it is documented in photographs, and a very close replica is in the Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth. The figures and the patterns on the cloth of honor of the dell’Orto panel are repeated almost exactly. Indeed, the incised contours of the figures in the gesso strongly suggest that the Kimbell version is a copy of the dell’Orto painting. In comparing these two works to the Straus panel, it is obvious that the pose of the Child is very similar, but not an exact copy. Variations are, of course, to be expected from an inventive artist like Bellini. The Child in the dell’Orto and Kimbell paintings is draped with a garment that is held together with a costly pin that leaves his arms, legs, and bottom free, but covers his genitals. The Child’s raised left arm in the Houston painting differs from the dell’Orto model, as do the placement of the Madonna’s hands and the inclination of her head, which are actually closer to those found in the Berlin version (see fig. 14.3). Remarkably, Bellini has returned to an earlier tradition by setting the figural group in front of a beautiful cloth of honor instead of positioning them before a landscape. This might be considered a step back, but can be attributed either to Bellini’s continuous search for different compositions or possibly to the patron who commissioned the painting. Although it is known that the dell’Orto painting was installed in a chapel in Santa Maria dell’Orto funded by Luca Navagero, there is no documented evidence of his having commissioned the painting.20 Proof of Bellini’s continued quest for new compositions is seen in a third version of the dell’Orto painting, also in the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin and dated slightly later. It corresponds very closely with the other two versions, but the cloth of honor is replaced by a rich red curtain.21 Another textile, the colorful and undoubtedly precious carpet draped across the stone parapet in the Straus panel, is an unusual feature in Bellini’s images of the Madonna and Child. The bare marble slab of the parapet is more easily understood as a reference to Christ’s tomb as well as a symbolic altar. Here, however, the insistence on precious materials probably harks back to the aesthetic embraced by his father, Jacopo, who was still rooted in the decorative International Gothic style.

In conclusion, the overall composition and many details of the Straus panel are consistent with those of the Berlin and dell’Orto paintings. Some are holdovers from earlier traditions, such as the goldfinch and the carpet on the parapet, but others, especially the Child’s nudity and the landscape, are innovations developed by Giovanni Bellini. These factors may not be enough to make a decisive attribution. The much-abraded and poorly restored figures of the Straus panel have in the past been a major stumbling block in the attribution of this work, and they still remain problematic. It is, however, interesting to note that in works firmly attributed to Bellini, it was the figures—not the background—that were mechanically copied from one panel to another. Whether that was the case here must remain speculation. Tempestini’s findings that the Straus panel was the product of an unnamed artist—not his son Giovanni—in Jacopo Bellini’s workshop must be seen in this context. The most recent treatment should give a better impression of the artist’s original intentions. Together with the superb landscape that has remained pristine and unrestored, this latest attempt will hopefully suffice to sustain an attribution to a great master, most likely Giovanni Bellini, who, according to the practice of the times, probably worked with assistants.

—Helga Kessler Aurisch

Notes

1. Anchise Tempestini, Giovanni Bellini (Paris: Gallimard, 2000), 9.

2. Oskar Bätschmann, Giovanni Bellini (London: Reaktion Books, 2008), 79.

3. Keith Christiansen, Giovanni Bellini and the Art of Devotion (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2004), 9.

4. Rona Goffen, Giovanni Bellini (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1989), 23.

5. F. Mason Perkins to Percy S. Straus, 2 November 1922, 24 January 1923, 19 February 1923, 25 March 1923, and 23 April 1924, the Edith A. an Percy S. Straus Collection, MS15, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, archives, document Perkins’s efforts to substantiate the attribution by leading scholars like Detlev von Hadeln, as well as explaining the controversy that erupted among rival dealers like Agnew’s and Duveen.

6. Carolyn C. Wilson, Italian Paintings, XIV–XVI Centuries, in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in association with Rice University Press and Merrell Holberton, 1996), 202.

7. Maite Leal, unpublished condition report, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, conservation files.

8. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 209.

9. Goffen, Giovanni Bellini, 35.

10. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 201, 213.

11. Tempestini, Giovanni Bellini, 186, ill. 11.

12. Christiansen, Giovanni Bellini, 8.

13. Christiansen, Giovanni Bellini, 9.

14. Christiansen, Giovanni Bellini, 14.

15. Bätschmann, Giovanni Bellini, 79.

16. Goffen, Giovanni Bellini, 28.

17. Goffen, Giovanni Bellini, 31.

18. Friedmann, Herbert, The Symbolic Goldfinch (Washington, DC: The Bollingen Foundation, 1946), 10.

19. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 209.

20. Christiansen, Giovanni Bellini, 11.

21. “Maria mit dem Kind, Giovanni Bellini,” Gemäldegalerie der

Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin—Preußischer Kulturbesitz, inv. 10A, id.smb.museum/object/863126.

Comparative Images

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has made every effort to contact all copyright holders for images and objects reproduced in this online catalogue. If proper acknowledgment has not been made, please contact the Museum.