The Fall of Man

Frame: 13 1/16 × 10 3/4 in. (33.2 × 27.3 cm)

Ainsworth, Maryan W. and Joshua P. Waterman, with contributions by Timothy B. Husband and Karen E. Thomas. German Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1350–1600. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art; distributed by Yale University Press, 2013.

Brinkmann, Bodo, ed. Cranach. Frankfurt: Städel Museum in association with Hatje Cantz, 2007; London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2007.

Campbell, Caroline, ed., with Stephanie Buck, Susan Foister, Gunnar Heydenreich, and Anne Woollett. Temptation in Eden: Lucas Cranach’s “Adam and Eve.” London: Courtauld Institute of Art in association with Paul Holberton Publishing, 2007.

Enke, Roland, Katja Schneider, and Jutta Strehle. Lucas Cranach der Jüngere, Entdeckung eines Meisters. Munich: Hirmer, 2015.

Eissenhauer, Michael, Dirk Syndram, Bernhard Maaz, Jeffrey Chipps Smith, and Julien Chapuis. Renaissance & Reformation: German Art in the Age of Dürer and Cranach, transl. by Steven Lindberg. Munich: Prestel Verlag, 2016.

Friedländer, Max, and Jakob Rosenberg. Die Gemälde von Lucas Cranach. Berlin: Deutscher Verein für Kunstwissenschaft, 1932.

Grimm, Claus, Johannes Erichsen, and Evamarie Brockhoff. Lucas Cranach, Ein Maler-Unternehmer aus Franken. Regensburg: Friedrich Pustet, 1994.

Hand, John Oliver, with the assistance of Sally E. Mansfield. German Paintings of the Fifteenth through Seventeenth Centuries. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1993.

Heard, Kate, and Lucy Whitaker with contributions by Jennifer Scott et al. The Northern Renaissance: Dürer to Holbein. London: Royal Collection Publications in association with Scala Publishers, 2011.

Schade, Werner. Cranach: A Family of Master Painters. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1980.

Scharf, Alfred. “Eine Darstellung des Sündenfalls von Lucas Cranach dem Jüngeren.” Der Cicerone, vol. 21 (1929): 697–98.

Snyder, James. The Northern Renaissance: Painting, Sculpture, and the Graphic Arts from 1350 to 1575. New York: Abrams, 1985.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Catalogue of the Edith A. and Percy S. Straus Collection. Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1945.

Werner, Elke, Anne Eusterschulte, and Gunnar Heydenreich, ed. Lucas Cranach der Jüngere und die Reformation der Bilder. Munich: Hirmer, 2015.

Wilson, Carolyn C. “Lucas Cranach the Younger: the 1549 Adam and Eve and Related Drawings.” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte v. 62 no, 4 (1999): 534–40.

Art historical scholarship has sadly neglected Lucas Cranach the Younger, the second son of the renowned Lucas Cranach the Elder. His father’s fame as the court painter to the Electors of Saxony and as a close friend of Martin Luther, with whom he developed the canon of Reformation imagery, has overshadowed the son’s oeuvre. Even his eulogist concentrated on the achievements of the father, mentioning the deceased only at the end.1 Lucas the Younger has generally been regarded as a mere follower of his father, without individuality or innovative input in the production of the fabled Cranach workshop, while at the same time it has been acknowledged that the success of the workshop was based on the consistent quality of often reproduced images like The Fall of Man, which limited any deviating contributions. In fact, the homogeneity of the works produced in the workshop was so great that even the most recent scholarship, with the advantages of modern technology, has been challenged to clearly identify the various hands. Besides those of his sons, only about a dozen different names of artists who worked in Cranach’s long-active workshop have surfaced.2

As was customary, Hans (c. 1513–1537) and Lucas (1515–1586) were trained in their father’s workshop from an early age, certainly by the late 1520s. In 1535, when he was twenty, Lucas the Younger is listed as receiving payments for his work done in the castle at Torgau, an extensive commission carried out by the Cranach workshop. He received three times the amount of a mere apprentice, a clear indication of his higher qualifications.3 When his older brother died suddenly during a sojourn in Italy just two years later, Lucas was recognized as his father’s artistic heir, destined to take over the large and prosperous business.4 The changeover seems to have taken place when his father had followed his longtime patron, Johann Friedrich, Elector of Saxony, into exile, in 1550.5 The question of attribution therefore pertains particularly to the years between 1535 and 1550. Scholars today, no longer content to follow Max Friedländer’s and Jakob Rosenberg’s assumptions that all exceptionally good paintings should be assigned to the father, and all weaker works to the son,6 are still struggling to isolate the younger Cranach’s works. However, in the case of The Fall of Man, dated 1549, Friedländer, who authenticated this painting as one of the earliest works definitely by Lucas Cranach the Younger, was immediately convinced of its outstanding quality. He described it an “exceptionally delightful” work and recommended its purchase highly to Percy S. Straus.7

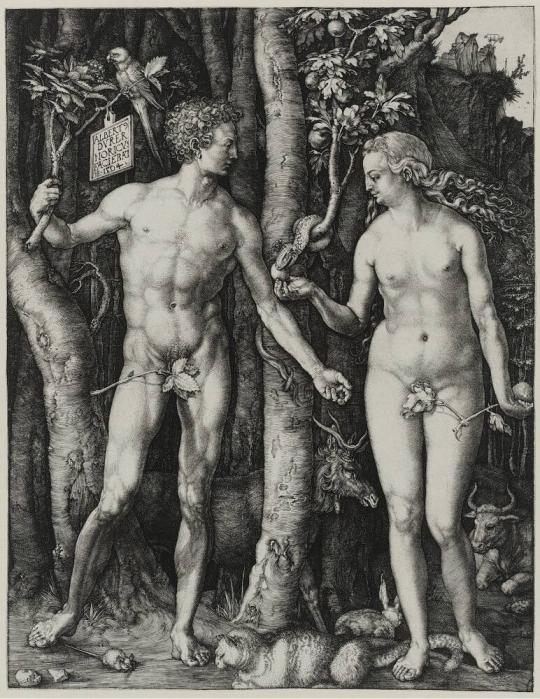

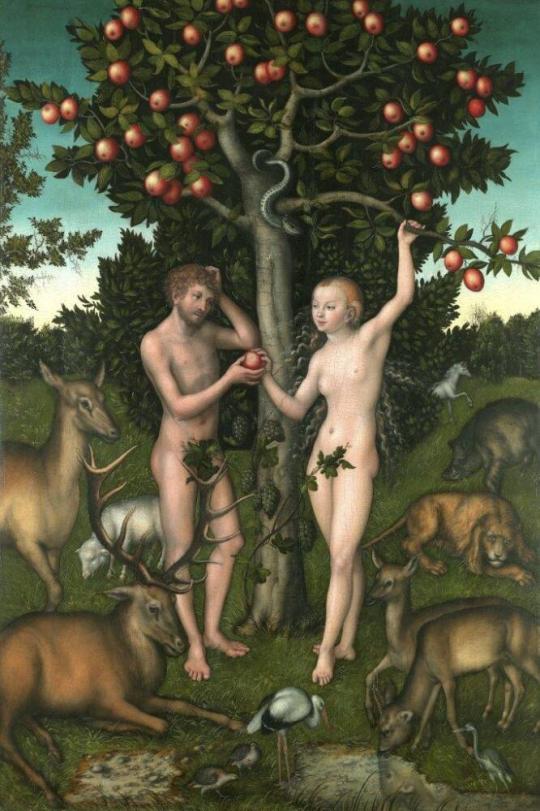

In this symmetrically balanced composition, Adam and Eve are depicted in the foreground of the Garden of Eden, standing to either side of the apple tree at the center. The trunk of the tree bears the Cranach signature—a winged snake—and the date 1549. Scholars have analyzed the different versions of this signature and have come to the conclusion that it was used as a hallmark of paintings produced by the workshop, used by different masters, including Lucas the Younger, rather than the personal signature of Lucas Cranach the Elder.8 The large snake wound around the trunk and lowest branch of the tree seems to be whispering to Eve, who is offering the apple with her right hand to Adam, his open left hand ready to receive it. Slender and blond, Adam displays an untroubled expression, and the equally beautiful, blond Eve wears a slight smile. The harmony of their expressions—still guilt-free before the fall—informs the open stance of their idealized bodies and is echoed in the paradisiacal landscape surrounding them. Cranach’s Garden of Eden is filled with an abundance of lively animals: deer are most numerous among them, but there are also a pair of wild boar, peacocks, swans, and rabbits, as well as an unusual pair of a fox and a cock in the far distance. Animal symbolism, long codified by Cranach’s time and easily legible by his contemporaries, adds another level of meaning to this well-known biblical scene. The horizon line is relatively low and—typical of the work of Cranach the Younger—the trees reaching up into the light sky are much more delicately painted than those making up the dense forests in his father’s depiction of the same subject. However, a comparison with the numerous versions of The Fall of Man produced in the Cranach workshop over the course of several decades makes the son’s dependence on these models manifest.

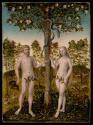

The earliest versions of this subject produced by his father’s workshop, two sets of panels today in Besançon and Warsaw, date to around 1510 and have always been regarded as Cranach the Elder’s reaction to Albrecht Dürer’s highly influential print of 1504 (fig. 32.1) and his monumental panels of 1507 (fig. 32.2).9 Whether there was any direct contact between these two luminaries of German painting is unclear, but Cranach certainly understood Dürer’s achievement of bringing the innovations of the Italian Renaissance to Northern Europe. Especially the nude bodies of Adam and Eve, idealized according to the canons of antiquity as rediscovered by the Italian Renaissance artists, constituted a watershed for Cranach and his Northern contemporaries.

While scholars continue to dispute the question whether Cranach had firsthand knowledge of the paintings,10 it is acknowledged that he and his workshop produced numerous panels showing the figures of Adam and Eve against a black background. According to the Cranach Digital Archive, there are fourteen versions altogether, painted between 1508/10 and 1546, that display an astonishing variety of positions and stances of the two figures.11 However, starting in 1526, as documented by the panel today in the Courtauld Institute (fig. 32.3), a new type of composition was introduced in which the figures are depicted in the Garden of Eden. Clearly harking back to Dürer’s print of 1504 (see fig. 32.1), which scholars firmly believe was known to him, Cranach the Elder went on to develop his own vision of the paradisiacal setting. During the following years, when Lucas the Younger was being trained and started to work in his father’s workshop, six other versions of this composition were produced there that display great diversity in the poses and gestures of the figures as well as in the landscape they inhabit.12

Although painted more than twenty years later, and despite several different versions having been produced in the meantime, the Straus painting depends heavily on the Courtauld panel (see fig. 32.3). Despite some striking differences, the overall compositions are extremely close. In the younger Cranach’s work in the Straus Collection, Adam and Eve are seen farther forward than in the father’s work, and the animals surrounding them are more numerous and smaller in scale. The dark thicket very typical of Cranach the Elder’s work has been replaced by delicately brushed trees that allow the sky, lighter in tonality than characteristic of the older painter, to shine through. The apple tree has been reduced in scope; the snake wrapped around its trunk, however, is proportionally larger in the later version.

The figures, although similar to those of the Courtauld panel, ultimately are an amalgamation of parts from several earlier versions. Eve’s elegant stance, with her left foot forward and her body turned slightly to her right, is first found on a panel at the Mainfränkische Museum, Würzburg, dated 1513–15, chronologically the direct precursor of the Courtauld version (see fig. 32.3), without, however, the motif of her raised left arm. The Straus Adam depends less on the Courtauld panel, but shares similarities with the Warsaw version, painted under the direct influence of the works by Dürer (see figs. 32.1, 32.2).

From these observations we can surmise that Lucas the Younger had a thorough knowledge of the works produced in his father’s workshop from the period before his birth up to the moment he painted the Straus panel. It is entirely possible that he worked on some of these versions himself; others he may have known through preparatory drawings or drawings of the finished works that had been retained for future reference in the workshop. A very detailed colored preparatory drawing of the figure of Adam (fig. 32.4), allows us further insight into Lucas the Younger’s painting practice. He obviously relied on the vocabulary developed in his father’s workshop, but combined different features from several older versions for a newly conceived figure. Before picking up his brushes, he worked out Adam’s figure with painstaking exactitude on paper. He then transcribed it onto the panel with only minute differences. We may assume that he did the same for the figure of Eve, but sadly no such drawing has surfaced to date. Besides this preparatory drawing of Adam, a detailed drawing of the whole composition, probably made after the finished painting, exists. It is also part of the Straus Collection (see cat. 33) and helps to substantiate the attribution of the painting to Lucas Cranach the Younger.13

The Straus Collection’s The Fall of Man, although one of the last in the long series of paintings produced by the workshop over four decades, seems to have served as a model for further paintings as well. A figure that corresponds closely to that of the Straus Eve has recently been discovered in the underdrawing of a portrait of Philip Melanchthon.14 As outlined by Jørgen Wadum, the underdrawing clearly points to the Cranach workshop, and dendrochronology has been used to date the panel to 1560,15 but it has not been clarified by whom or even when the two superimposed images were painted. Perhaps technological tools as yet unknown will one day provide an answer to this and to the many remaining questions still confronting the Cranach scholarship.

—Helga Kessler Aurisch

Notes

1. Roland Enke, Katja Schneider, and Jutta Strehle, Lucas Cranach der Jüngere, Entdeckung eines Meister (Munich: Hirmer, 2015), 32.

2. Claus Grimm, Johannes Erichsen, and Evamarie Brockhoff, Lucas Cranach, Ein Maler-Unternehmer aus Franken (Regensburg: Friedrich Pustet, 1994), 174–75.

3. Enke, Schneider, and Strehle, Lucas Cranach der Jüngere, 149.

4. Enke, Schneider, and Strehle, Lucas Cranach der Jüngere, 140.

5. Bodo Brinkmann, ed., Cranach (Frankfurt: Städel Museum in association with Hatje Cantz, 2007; London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2007), 23–24.

6. Enke, Schneider, and Strehle, Lucas Cranach der Jüngere, 29.

7. Max Friedländer to Percy S. Straus, 16 April 1929, the Edith A. and Percy S. Straus Collection, MS 15, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, archives.

8. Grimm, Erichsen, and Brockhoff, Lucas Cranach, 184, 190.

9. Caroline Campbell, ed., with Stephanie Buck, Susan Foister, Gunnar Heydenreich, and Anne Woollett, Temptation in Eden: Lucas Cranach’s “Adam and Eve” (London: Courtauld Institute of Art in association with Paul Holberton Publishing, 2007), 21.

10. Campbell, Temptation in Eden, 7.

11. Stiftung Museum Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf / Cologne University of Applied Sciences, Cranach Digital Archive, accessed December 2, 2020, http://lucascranach.org.

12. Stiftung Museum Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf / Cologne University of Applied Sciences, Cranach Digital Archive, accessed December 2, 2020, http://lucascranach.org.

13. Enke, Schneider, and Strehle, Lucas Cranach der Jüngere, 272. The relationship of the drawing and the painting had been thoroughly discussed by Carolyn. C. Wilson, “Lucas Cranach the Younger: the 1549 Adam and Eve and Related Drawings,” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 62, no. 4 (1999): 534-40.

14. Elke Werner, Anne Eusterschulte, and Gunnar Heydenreich, eds., Lucas Cranach der Jüngere und die Reformation der Bilder (Munich: Hirmer, 2015), 197.

15. Werner, Eusterschulte, and Heydenreich, Lucas Cranach der Jüngere, 198.

Comparative Images

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has made every effort to contact all copyright holders for images and objects reproduced in this online catalogue. If proper acknowledgment has not been made, please contact the Museum.