Charles Louis, Elector Palatine

Frame: 51 11/16 × 45 in. (131.3 × 114.3 cm)

Alsteens, Stijn. “A Portraitist’s Progress.” In Van Dyck: The Anatomy of Portraiture, 1–38. New York: The Frick Collection, 2016.

Alsteens, Stijn, and Adam Eaker. Van Dyck: The Anatomy of Portraiture. New York: The Frick Collection, 2016.

Barnes, Susan J. “Van Dyck in Italy.” In Van Dyck: A Complete Catalog of the Paintings, 145–49. New Haven: Paul Mellon Center for Studies in British Art and Yale University Press, 2004.

Barnes, Susan J., Nora De Poorter, Oliver Millar, and Horst Vey. Van Dyck: A Complete Catalog of the Paintings, no. IV 70. New Haven: Paul Mellon Center for Studies in British Art and Yale University Press, 2004.

Clapham, J. H. “Charles Louis, Elector Palatine, 1617–1680: An Early Experiment in Liberalism.” Economica (New Series) 7, no. 28 (November 1940): 381–96.

Cust, Lionel. Anthony van Dyck: An Historical Study of His Life and Works. London: G. Bell and Sons, 1900.

Glück, Gustav. Van Dyck. Vol. 8 of Klassiker der Kunst series. Stuttgart, 1931, 514.

Gordenker, Emilie E. S. Van Dyck and the Representation of Dress in Seventeenth-Century Portraiture. Turnhout: Brepols, 2001.

Larsen, Erik. The Paintings of Anthony van Dyck. Vol. 2, no. 935. Freren: Luca Verlag, 1988.

Millar, Oliver. “Van Dyck in England.” In Van Dyck: A Complete Catalog of the Paintings, 419–28. New Haven: Paul Mellon Center for Studies in British Art and Yale University Press, 2004.

Millar, Oliver. Van Dyck in England. London: National Portrait Gallery, 1982.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Catalogue of the Edith A. and Percy S. Straus Collection. Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1945.

Luijten, Ger, and Robert Zijlma, eds. New Hollstein: German Engravings, Etchings, and Woodcuts. 29 vols. Rotterdam: Sound and Vision Interactive, 1996–1999.

Poorter, Nora De. “Van Dyck in Antwerp and London: The First Antwerp Period.” In Van Dyck: A Complete Catalog of the Paintings, 15–19. New Haven: Paul Mellon Center for Studies in British Art and Yale University Press, 2004.

Portrait of Charles Louis, Elector Palatine, by Sir Anthony van Dyck. London: Chiswick Press, n.d.

Smith, John. A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish and French Painters. Vol. 3. London: Smith and Son, 1829, 163.

Springell, Francis C. Connoisseur and Diplomat: the Earl of Arundel’s embassy to Germany in 1636 as recounted in William Crowne’s diary, the Earl’s letters and other contemporary sources with a catalogue of the topographical drawings made on the journey by Wenceslaus Hollar. London: Maggs Brothers, 1963.

Stephens, Frederic George. Van Dyck. London: H. Good and Son, Printers, 1886–1887.

Van Dyck and Britain. London: Tate Britain, 2009.

Vey, Horst. “Van Dyck in Antwerp and Brussels: The Second Antwerp Period.” In Van Dyck: A Complete Catalog of the Paintings, 240–245. New Haven: Paul Mellon Center for Studies in British Art and Yale University Press, 2004.

ProvenanceThomas Howard, Earl of Arundel (1586–1646); George Edmonstoune Cranstoun, Lord Corehouse (d. 1850); by descent to his great-great nephew Colonel Charles Edmonstoune-Cranstoun of Corehouse (d. 1950); [purchased by Robert Langton Douglas, London, December 24, 1930]; purchased by Percy S. Straus, New York, May 1931; bequeathed to MFAH, 1944.Anthony van Dyck, born in 1599, painted portraits and histories in his native Antwerp and in Italy before settling in England. He is best remembered for the casually refined poses and brilliant coloring that characterize his portraits of English aristocrats, including his many portraits of Charles I painted from 1632 to the artist’s death in 1641. The elegant style Van Dyck introduced would dominate English portraiture for two centuries after his death.1

Van Dyck began his training at the age of ten in Antwerp as apprentice to Hendrik van Balen (1575–1632). His precocious talent and self-confidence are evident in his first dated painting, Portrait of an Elderly Man (1613), which the fourteen-year-old artist proudly inscribed with his own age, as well as that of the sitter.2 Van Dyck was running his own studio by the age of sixteen and was admitted to the Antwerp Guild of St. Luke, the painters’ guild, in 1618.3 During these years he also worked with the most successful and famous painter in Northern Europe at the time, Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640), assisting Rubens with numerous commissions and executing works according to Rubens’s designs.4

Van Dyck traveled to England briefly in 1620, followed by a stay in Italy from 1621–1627. In Venice he studied the works of Titian, whose heightened color palette would become a feature of Van Dyck’s portrait style, but found the greatest demand for his portraits in Genoa. Van Dyck returned to England in 1632, and within a short time of his arrival was named “Principalle Paynter in Ordinary to their Majesties at St. James’s.” A generous stipend in addition to payment for services, frequent gifts, luxurious lodgings, and the freedom to undertake dozens of private commissions kept Van Dyck in London until his death in 1641.

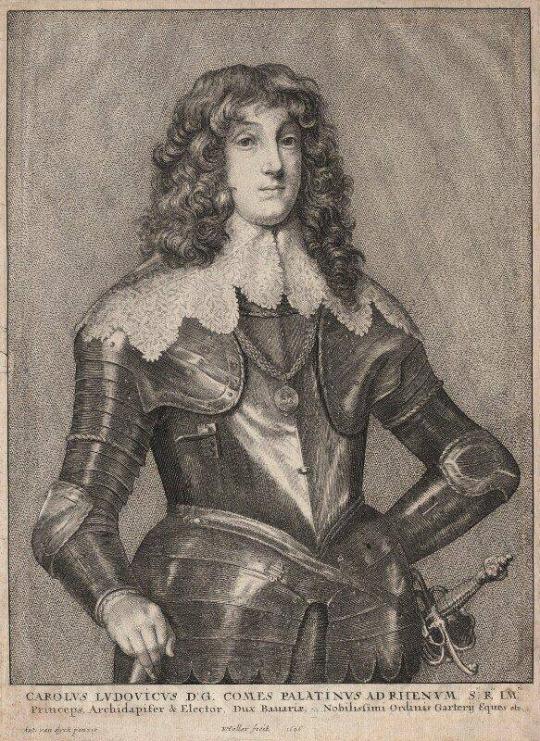

The Straus Collection portrait was painted during Van Dyck’s second and final stay in England. It depicts Charles Louis (or Karl I Ludwig Kurfürst von der Pfalz, 1617–1680), Elector Palatine, at the age of about nineteen. Charles Louis was the eldest surviving son of Frederik V, Elector Palatine, and Elizabeth of Bohemia, sister of the English King Charles I. Frederik accepted the crown of Bohemia in 1619, angering the Holy Roman Emperor and escalating the political tensions of the Thirty Years’ War. Frederik’s and Elizabeth’s reign lasted only a year and earned them the sobriquet “The Winter King and Queen.” They lost their territories in the Palatinate in the ensuing hostilities. Frederik died in 1632, leaving his fifteen-year-old son, Charles Louis, as heir.

Charles Louis and his mother spent much of the 1630s in England trying to garner the support of Charles I in their efforts to regain the Palatinate. With the future of his territories foremost in his mind, Charles Louis also developed close relationships with the King’s parliamentary opponents, whom he thought might be sympathetic to his cause. The relationship between uncle and nephew soured and Charles did not provide the help Charles Louis sought.5 While in England, Charles Louis spent much time with Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel, for whom it is believed Van Dyck painted this portrait. Howard was a close friend of Elizabeth of Bohemia and an advisor to both of her sons, Charles Louis and his younger brother Rupert (1619–1682), and in the 1630s urged Charles to take a strong stand against Spain and its Catholic allies in central Europe through military support of Charles Louis’s claims in the Palatinate.6

The portrait was likely painted early in 1637 before Charles Louis and Rupert left England.7 In that year Van Dyck also painted a double portrait of the brothers, which now hangs in the Louvre (fig. 36.1). He altered the elder brother’s pose slightly in the Louvre canvas, perhaps using a portrait painted for Thomas Howard from a year or two earlier as a model.8 In the Straus portrait, Charles Louis rests his right hand on a baton, his left arm cocked behind his hip. A broad linen lace collar tops his polished armor. He wears the “Lesser George,” the badge of the Order of the Garter, on a gold chain. A fashionable lovelock hangs over his left shoulder. The color palette in this canvas is more muted than those in Van Dyck’s English portraits that feature brilliant, jewel-toned silks. The darkly gleaming armor, however, suggests the “heroic virtue” appropriate to Charles Louis’s military and political aspirations.9

The portrait shows the lively handling of paint for which Van Dyck is known, especially in the right hand. Changes to the composition made in the course of painting are visible today. The position of the right arm was changed twice; pentimenti show its earlier, higher positions on the canvas. Wenceslaus Hollar’s 1646 engraving after the portrait reproduces the final pose (fig. 36.2).10 Van Dyck rarely created preparatory drawings before painting; indeed visitors to his studio remarked on the speed with which he executed a portrait directly onto the canvas without the aid of sketches, a practice known as fa presto that Van Dyck observed in Italian portraiture.11

Before Percy Straus purchased the portrait from R. Langton Douglas, the dealer assured him of its authenticity. In his letters to Straus, Langton Douglas warns his client to be wary of inexpensive portraits attributed to Van Dyck, as these are studio productions at most retouched by the master. Even though Langton Douglas offered Straus a low price (according to the dealer), he also provided Straus with hand-written assurances from Ludwig Burchard, the preeminent Rubens scholar of the day, and Gustav Glück, director of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, of the portrait’s authenticity. The portrait hung in the dining room of the New York apartment with other English portraits in the Straus collection.12 Since Burchard and Glück made their assessments in the 1930s, scholarly opinion on the painting has varied. Larsen judged the work to be autograph, although Millar deemed it a studio production only retouched in passages by the master himself.13 A commanding argument for Van Dyck’s authorship is the inscription on Hollar’s etching: “Ant. van Dyck pinxit / WHollar fecit.” Thomas Howard was an ardent collector, a true connoisseur, and Hollar’s employer. It is unlikely that he would have accepted a studio production from Van Dyck or that Hollar would have etched an assistant’s work. The remains of a later inscription can be seen in the lower left corner.14

—Michelle Packer

Notes

1. Erik Larsen, The Paintings of Anthony van Dyck (Freren: Luca Verlag, 1988); Susan J. Barnes, “Van Dyck in Italy,” in Van Dyck: A Complete Catalog of the Paintings (New Haven: Paul Mellon Center for Studies in British Art and Yale University Press, 2004), 145–49; and Van Dyck and Britain, (London: Tate Britain, 2009).

2. Anthony van Dyck, Portrait of an Elderly Man, 1613, oil on canvas, 24 3/4 x 17 1/8 in. (63 x 43.5 cm), signed and dated upper center: AETATIS. SVE. 70. ANNO. 1613. AD.F.AETA.SVE 14. Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels, inv. no. 6858.

3. Laws that prohibited painters from working without guild membership were not enforced in Antwerp, and thus Van Dyck was able to establish his own studio two years before becoming a member of the Guild of St. Luke; see Erik Larsen, The Paintings of Anthony van Dyck (Freren: Luca Verlag, 1988), 1:108–9.

4. Van Dyck was probably not apprenticed to Rubens, although some documents do refer to him as a “pupil.” He would not have worked as an apprentice while also running an independent studio. It is more likely that the younger Van Dyck recognized he could learn much from and make valuable contacts through Rubens, while the elder artist saw the opportunity to make use in his own busy studio of Van Dyck’s evident talent. Their personal relationship seems to have been quite close, and their working relationship to have evolved as needs demanded; see Larsen, The Paintings, vol I., 108–9; Nora De Poorter, “Van Dyck in Antwerp and London: The First Antwerp Period,” in Van Dyck: A Complete Catalog of the Paintings (New Haven: Paul Mellon Center for Studies in British Art and Yale University Press, 2004), 17–19; and Oliver Millar, “Van Dyck in England,” in Van Dyck: A Complete Catalog of the Paintings (New Haven: Paul Mellon Center for Studies in British Art and Yale University Press, 2004), 420.

5. The Elector left England in 1638 but returned in 1644 at the invitation of Parliament. He never reconciled with the King, who accused him of aspiring to take the English throne. Charles Louis left England shortly after the execution of his uncle. The end of the Thirty Years’ War restored him to most of his territories in present-day Germany and he focused his efforts from that point on post-war rebuilding; see J.H. Clapham, “Charles Louis, Elector Palatine, 1617–1680: An Early Experiment in Liberalism,” Economica (New Series) 7, no. 28 (November 1940): 387–96.

6. Francis C. Springell, Connoisseur and Diplomat: the Earl of Arundel’s embassy to Germany in 1636 as recounted in William Crowne’s diary, the Earl’s letters and other contemporary sources with a catalogue of the topographical drawings made on the journey by Wenceslaus Hollar (London: Maggs Brothers, 1963), 37.

7. The brothers left England together on June 25, 1637; see Oliver Millar, Van Dyck in England (London: National Portrait Gallery, 1982), 75.

8. Anthony van Dyck, Thomas Howard, 14th Earl of Arundel, with his Grandson, Thomas, later 5th Duke of Norfolk, c. 1635–36, oil on canvas, 57 x 48 in. (144.8 x 121.9 cm), West Sussex, The Duke of Norfolk, Arundel Castle.

9. For a discussion of military dress in Van Dyck’s portraits, see Emilie E.S. Gordenker, Van Dyck and the Representation of Dress in Seventeenth-Century Portraiture (Turnhout: Brepols, 2001), 21–22.

10. New Hollstein: German Engravings, Etchings, and Woodcuts, eds. Ger Luijten and Robert Zijlma, vol. III, (Rotterdam: Sound and Vision Interactive, 1996–1999), 122.

11. Fa presto literally means “work quickly.” Visitors to Van Dyck’s studio remarked on the speed with which he painted. The seventeenth-century biographer Gian Pietro Bellori reported that Van Dyck often painted two or more portraits per day, working from one or two sittings. For a discussion of Van Dyck’s working method, see Stijn Alsteens, “A Portraitist’s Progress,” in Van Dyck: The Anatomy of Portraiture (New York: The Frick Collection, 2016), 18–20; Susan J. Barnes, “Van Dyck in Italy,” in Van Dyck: A Complete Catalog of the Paintings (New Haven: Paul Mellon Center for Studies in British Art and Yale University Press, 2004), 146; Nora De Poorter, “Van Dyck in Antwerp and London: The First Antwerp Period,” in Van Dyck: A Complete Catalog of the Paintings (New Haven: Paul Mellon Center for Studies in British Art and Yale University Press, 2004), 16; Horst Vey, “Van Dyck in Antwerp and Brussels: The Second Antwerp Period,” in Van Dyck: A Complete Catalog of the Paintings (New Haven: Paul Mellon Center for Studies in British Art and Yale University Press, 2004), 242; and Erik Larsen, The Paintings of Anthony van Dyck (Freren: Luca Verlag, 1988), 1:355 et passim.

12. R. Langton Douglas to Percy S. Straus, the Edith A. Straus and Percy S. Straus Collection, MS 15, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, archives.

13. Oliver Millar, “Van Dyck in England,” in Van Dyck: A Complete Catalog of the Paintings (New Haven: Paul Mellon Center for Studies in British Art and Yale University Press, 2004), 486, judges the Straus portrait to be a copy with some retouching of the right arm and hand by Van Dyck. Erik Larsen, The Paintings of Anthony van Dyck (Freren: Luca Verlag, 1988), 2:366, calls the portrait “an authentic and very good portrait by Van Dyck.”

14. A copy of the portrait is at Chequers, the official country residence of the British Prime Minister.

Comparative Images

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has made every effort to contact all copyright holders for images and objects reproduced in this online catalogue. If proper acknowledgment has not been made, please contact the Museum.