The Holy Family

Frame: 27 7/8 × 20 1/2 in. (70.8 × 52.1 cm)

Ainsworth, Maryan Wynn. “Underdrawings in Paintings by Joos van Cleve at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.” Dessin sous-jacent dans la peinture , colloque IV, 29–30–31 octobre 1981:Le problème de l’auteur de l’oeuvre de peinture; contribution de l’étude du dessin sous-jacent à la question des attributions , edited by Roger Van Schoute and Dominique Hollanders-Favart, 161–67. Louvain-la-Neuve: Collège Érasme, 1982.

Evans, Mark. “Joos van Cleve: Aachen.” Burlington Magazine 153, no. 1299 (2011):429–31.

Friedländer, Max. Die Niederla¨ndischen Meister. Berlin: J. Bard, 1930.

Friedländer, Max. Early Netherlandish Painting. Vol . 9a. New York: Praeger, 1972.

Hand, John Oliver. “Joos van Cleve: the Early and Mature Paintings.” PhD diss., Princeton University, 1978.

Hand, John Oliver. Joos van Cleve. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2004.

Heard, Kate, and Lucy Whitaker. The Northern Renaissance: Durer to Holbein. London: Royal Collection Publications, in association with Scala Publishers, 2013.

Jones, Susan Frances. Van Eyck to Gossaert: Towards a Nothern Renaissance. London: National Gallery, 2011. www.nationalgallery.org.uk/artists/joos-van-cleve

Leeflang, Micha. Joos van Cleve: A Sixteenth-Century Antwerp Artist and His Workshop. Turnhout: Brepols, 2015.

Leeflang, Micha and Peter Klein. “Dating Panel Paintings: The Workshop of Joos van Cleve ; a Dendrochronological and Art Historical Approach.” In Peinture ancienne et ses proce´de´s , edited by He´le`ne Verougstraete and Jacqueline Couvert. Leuven: Peeters, 2006.

Mensger, Ariane. “ Die exakte Kopie oder: die Geburt des Ku¨nstlers im Zeitalter seiner Reproduzierbarkeit.” Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek (NKJ) / Netherlands Yearbook for History of Art 59 (2009): 19–221 . Scailliérez, Cécile. Joos van Cleve au Louvre. Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1991.

Silver, Larry. “Leonardo in the Lowlands.” In Artistic Innovations and Cultural Zones, edited by Ingrid Ciulisova. Bratislava: VEDA; Frankfurt: M. Lang (2015): 8–39.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Catalogue of the Edith A. and Percy S. Straus Collection. Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1945.

Van den Brink, Peter, with Alice Taatgen and Heinrich Becker. Joos van Cleve: Leonardo des Nordens. Stuttgart: Belser Verlag, 2011.

Zanelli, Gianluca, Maria Clelia Galassi, Marie Luce Repetto, and Daniele Sanguineti. Joos van Cleve : il trittico di San Donato. Genoa: Sagep editori, 2016.

ProvenanceBaron Maurice de Rothschild, Paris; [Wildenstein & Co., Inc., New York, January 28, 1930]; Mr. Percy S. Straus,1930; bequeathed to MFAH, 1944.Joos van Cleve, who has been called the “Leonardo of the North” thanks to his remarkable technique and sensitive use of color, was a greatly influential Netherlandish artist active in the first half of the sixteenth century.1 His works were highly regarded during his lifetime, but his name slipped into anonymity after his death. Associated with two altarpieces from Cologne, he was long known only as “Master of the Death of the Virgin.” His works were misattributed, to Jan van Scorel and many others, until his true identity was discovered by Eduard Firmenich-Richartz in 1894.2 In his authoritative Early Netherlandish Painting, published between 1924 and 1937, Max Friedländer devoted an entire volume to the artist now known as Joos van Cleve. Thus, at the time when the Straus Collection was being formed, his newly reassessed works were once again very desirable.

Neither the exact date nor the birthplace of the artist, whose real name was Joos van der Beke, are known.3 It is assumed that he was born in Cleve (Kleve), a town on the Lower Rhine, sometime between 1485 and 1490. Early in his career, he worked with Jan Joest on the wings of an altarpiece, completed between 1505 and 1509, as evidenced by the unusual inclusion of a self-portrait.4 His earliest independent works, Adam and Eve, dated 1507 and today in the Musée du Louvre, are also wings of an altarpiece whose whereabouts is unfortunately unknown.5 Joos was documented to have been in Antwerp as of 1511, when he joined the Guild of Saint Luke as a vreymeester, a free master. He apparently operated a workshop as of 1516, since he repeatedly registered apprentices with the guild. From 1519, coincidentally the year of his marriage to Anna Vyts, he frequently held positions of responsibility in the guild. His son, Cornelius, who also became a painter, was born in 1520, followed by a daughter in 1522. Persistent confusion exists in the literature between the father and the son, who in later life became mentally unstable, an affliction not suffered by the father.6

Religious paintings represent the largest part of Joos van Cleve’s output, and he is best known for his magnificent altarpieces, such as Death of the Virgin (Alte Pinakothek, Munich), The Adoration of the Magi (Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden), and the Enthroned Virgin (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna). Working in the Northern tradition of such artists as Jan van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden, Albrecht Dürer, Jan Gossaert, Quinten Metsys, and Joachim Patinir, whose inventive landscapes he adapted in his own works, Joos also incorporated the innovations of his Italian contemporaries. Leonardo da Vinci’s painterly technique had an especially significant impact on both his religious paintings and his portraiture, which he practiced virtually exclusively between 1529 and 1535 while working at the court of the French king Francis I. From the time of Joos’s return to Antwerp in 1536 until his death, his workshop was extremely busy, turning out large numbers of devotional paintings for private use as well as many portraits.

The subject of the Holy Family was of crucial importance to Joos, whose innovations “reflect a change in religious sentiment and a response to the need for a new type of nonnarrative devotional image.”7 While the work in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (fig. 29.1), his earliest version of this subject, represents a compositional type that follows Jan van Eyck’s famous Lucca Madonna, in which the Christ Child is seated on the Virgin’s lap, a second type is documented by the Holy Family in the National Gallery, London (fig. 29.2), dated around 1520–25.8 Here, the child is standing on a ledge in the foreground, reaching for his mother’s breast, while Saint Joseph, seen behind a lectern, is reading. An infrared reflectography (IRR) examination has revealed a major compositional change. The Christ Child, originally held in the same position as in the Metropolitan’s work, was changed into a standing position (fig. 29.3). John Hand has argued that this type presupposes a familiarity with Italian models, in particular with the works of Bernardino Luini, a follower of Leonardo.9 This “modern” image of the Holy Family seems to have been eagerly accepted in the North, since Joos and his workshop produced a large number of paintings of the subject with varying details. Only four of the extant works—the Metropolitan Museum’s version (see fig. 29.1), the National Gallery’s painting (see fig. 29.2), the painting in the Currier Museum of Art, in which the Christ Child, held by the Virgin, faces to the left, and one work whose whereabouts is unknown—are believed to be entirely autograph, while thirteen are considered to have been produced by Joos’s workshop (some with the master’s input), and another thirteen to be copies.10

The work in the Straus Collection, which is believed to have been produced in Joos’s workshop, follows the example of the London painting in its overall composition, use of the uniformly green background, and emphasis of the Christ Child’s human need of nourishment. In both versions, Christ’s divinity is symbolized by the still life of emblematic fruits and flowers displayed on the ledge. However, the cherries found in the London version, representing the fruits of Paradise, have been replaced with a pink, a symbol of love and faithfulness, being offered by the Madonna, and the coral chain has been eliminated entirely. The change in Saint Joseph’s headgear is also remarkable: the straw hat has been substituted by a darker, softer hat that adds a greater measure of solemnity to the saint, whose popularity and veneration had been steeply on the rise since Pope Sixtus IV had introduced the first feast day in his name in 1479.11 Among all the versions of Joos’s Holy Family, the Straus painting is closest to the work in the Hermitage in Saint Petersburg, considered to be either from the workshop of Joos or a copy, from which it deviates mainly in its brocaded cloth of honor behind the Virgin.

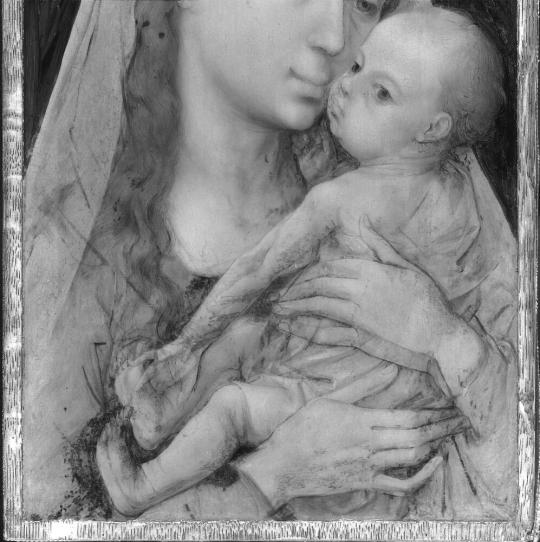

The attribution of the Straus Collection’s Holy Family to the workshop of Joos van Cleve was substantiated by IRR (fig. 29.4). It revealed a series of holes made by pricking through a cartoon to copy the outlines of a drawing onto the canvas. The underdrawing for the painting was then accomplished by connecting the dots to serve as the guideline for the application of paint. This widely used technique simplified a mass-production style of output by Joos’s workshop, which reached its largest number of assistants after the master’s return to Antwerp in 1535. He registered three apprentices with the guild between 1535 and 1536. Naturally, there are visible differences in the hands that executed the works, but to Joos’s great credit, the quality of the works that left his studio was consistently high.12 Although difficult to understand today, when the singularity and originality of a work of art are so highly prized, the workshop practice of creating multiple copies of the same composition was considered normal at a time when most patrons commissioned a copy, perhaps with individual variations, rather than an entirely new work. Running a large and productive workshop to meet the demand for works of art was a sign of success, and one that Joos enjoyed to a large degree.

—Helga Kessler Aurisch

Notes

1. Peter Van den Brink with Alice Taatgen and Heinrich Becker, Joos van Cleve: Leonardo des Nordens. exh. cat. (Stuttgart: Belser Verlag, 2011); John Oliver Hand, Joos van Cleve (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2004), 1.

2. Hand, Joos van Cleve, 9–11.

3. Max Friedländer, Early Netherlandish Painting, vol. 9a (New York: Praeger, 1972), 18.

4. Hand, Joos van Cleve, 5.

5. Cécile Scailliérez, Joos van Cleve au Louvre (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1991), 16–18.

6. Hand, Joos van Cleve, 5.

7. Hand, Joos van Cleve, 54.

8. “Joos van Cleve,” National Gallery, London, accessed March 22, 2017, www.nationalgallery.org.uk/artists/joos-van-cleve

9. Hand, Joos van Cleve, 54, ill. 53, Bernardino Luini, Virgin and Child with a Colombine, The Wallace Collection, London.

10. For full listings of the autograph, workshop, and copies of the Holy Family, compare Friedländer Early Netherlandish Painting, nos. 64–66, and Hand, Joos van Cleve, cats. 32–32.3, 33–33.15, 63–63.8.

11. Hand, Joos van Cleve, 54.

12. Micha Leeflang, Joos van Cleve: A Sixteenth-Century Antwerp Artist and His Workshop (Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2015), 71.

Comparative Images

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has made every effort to contact all copyright holders for images and objects reproduced in this online catalogue. If proper acknowledgment has not been made, please contact the Museum.