The attribution of these two panels to Allegretto Nuzi was first proposed by Charles Perkins in 1922, was published as such by Lionello Venturi in 1931, and has been widely accepted by other leading scholars in the field of trecento Italian painting.1 Nuzi is believed to have been born in Fabriano, a town famous for its pulp paper production and located in the Ancona province of Italy, on the border with Tuscany. His signature “Allegritus de Fabriano,” found on a number of works, alludes to his birthplace, but in 1346 he registered with the Florentine guild of the Arte dei Medici e Speziali, which included painters, as “Allegrettus Nuccii de Senis.” This somewhat confusing designation as “of Siena” has been interpreted as referencing the city he resided in before coming to Florence.2

Indeed, his early style reveals a closeness to the Lorenzetti brothers of Siena, as well as to Bernardo Daddi and Maso di Banco.3 However, his earliest firmly datable work is the left lateral panel of a triptych today in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., of 1354, executed at a time when Nuzi was in frequent and prolonged contact with artists in Florence.4 Here, Andrea Orcagna and his followers exerted considerable influence on his work, as did Puccio di Simone, who later followed him to Fabriano.5 His continued presence in Fabriano is documented by his registration as a member of the Confraternity of Santa Maria del Mercato in 1348, 1350, and 1363, when he was elected prior. A handful of signed and dated works on panel all fall into the 1360s and early 1370s.6The two panels in the Straus Collection are from this period as well. Four rows of saints and angels are arranged in groups of twos and threes on each panel. The front row of the left panel includes Saint Mary Magdalen and Saint Lawrence, recognizable by their respective attributes of ointment jar and iron grill, the instrument of Saint Lawrence’s torture. In the center of the row above them, Saint Elizabeth of Hungary (or Thuringia) stands at the center, crowned but wearing a nun’s habit. She has gathered up her skirt to cradle the red and white roses, evidence of her famous Miracle of the Roses. She is flanked by an unidentified Franciscan monk (possibly Saint Anthony of Padua) and a female martyr carrying a palm frond, whose idealized female type recurs in the figures of the top two rows. Directly above Saint Elizabeth, a remarkably beautiful young woman, adorned with a large diadem, looks out directly toward the viewer. Neither she nor the other figures have so far been identified, although the habited woman may be Saint Clare of Assisi.7 On the right panel, the most outstanding figure is a man draped in a blue mantle adorned with golden fleurs-de-lis of the French king. His miter and bishop’s crook identify him as Louis of Anjou, Bishop of Toulouse, who had a claim on the French crown, but who chose the church instead.8 He, like his royal counterpart Saint Elizabeth on the opposite panel, was closely associated with the Third Order of Franciscans.9 The other identifiable saints on this panel are Saint Catherine, standing next to Saint Louis; Saint Paul, seen directly above Saint Louis; and possibly Saint Anthony Abbot, standing next to him and holding a book. Saint Jerome, wearing a cardinal’s hat with a pen in hand; Saint Dominic, with a lily; and Saint Ursula, with a banner, make up the third row. The paired figures at the very top of both panels, with large haloes like the saints below them but without any attributes, are believed to represent angels.10

The stylistic hallmarks of these panels are a remarkable rich presentation, dominated by the gold ground and the heavy, intricately pounced golden haloes. The richness extends to the sumptuous clothing, which is rendered with great attention to detail, revealing a love for luxurious materials that predates the ornate style of Gentile da Fabriano, one of the outstanding representatives of the International Style. The “intensity and intelligence” of the figures,11 as well as the delicate balance in their arrangement across the panels, testify to the mastery of Nuzi, who unites in his works stylistic elements of both Siena and Florence.

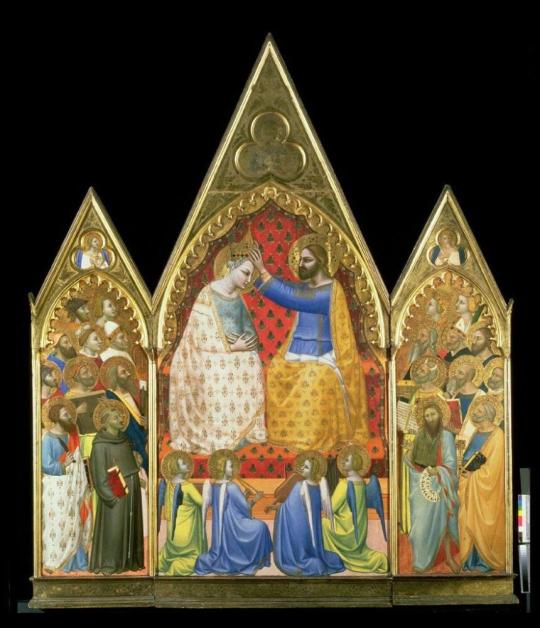

Lionello Venturi was the first to have proposed the connection of the Straus panels with an altarpiece in the Southampton City Art Gallery (fig. 5.1). He had attributed that triptych, whose central panel depicts the Coronation of the Virgin and whose later panels of saints and angels correspond compositionally and stylistically with the Straus panels, to Nuzi.12 Incontrovertible proof of their original connection is the part of Saint Lawrence’s grill, cut off on the Houston panel but continuing onto the left lateral panel of the Southampton altarpiece. When acquired by Percy Straus in 1922, the panels had the same molding around at the top as the Southampton panels, as documented by photographs, traces of which are still visible today. They had, however, been cut down by one-sixth of their height, probably due to damage of one or both panels.13 Neither the Southampton triptych nor the two Straus panels have yet undergone dendrochronological testing or pigment analysis to substantiate the scholarly assumption, but the visual evidence is indisputable.

Federico Zeri has put forth the argument that because of the dominance of Franciscan saints found on the panels of the pentatych, it was most likely designated for the high altar of the Church of San Francesco in Nuzi’s native city of Fabriano.14 Unfortunately, the church was demolished in 1864, and the reconstruction of the high altar remains theoretical. Furthermore, this theory has not found universal support, since scholars have proposed widely divergent dates for the creation of the pentatych. Zeri argues for a date around 1370 and a collaboration with Francescuccio Ghissi, whereas earlier scholars like Alessandro Marabottini have pointed to its similarity with Bernardo Daddi and placed it in the early part of Allegretto’s career.15

—Helga Kessler Aurisch

Notes

1. Carolyn C. Wilson, Italian Paintings, XIV–XVI, Centuries in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in association with Rice University Press and Merrell Holberton, 1996), 58.

2. "Allegretto Nuzi Biography," National Gallery of Art, www.nga.gov/collection/artist-info.5525.html.

3 . Wilson, Italian Paintings, 52.

4 . "Allegretto Nuzi Biography," National Gallery of Art.

5 . "Allegretto Nuzi Biography," National Gallery of Art.

6 . Wilson, Italian Paintings, 52.

7 . Wilson, Italian Paintings, 56.

8 . Allen Banks Hinds, "Saint Louis of Toulouse,' A Garner of Saints, 1900, in CatholicSaints.Info, April 2017, catholicsaints.info/saint-louis-of-toulouse.

9 . These Brothers and Sisters of Penance, or tertiaries, were both vowed and lay people who wished to live according to the saint’s rule, but could not enter a convent or monastery because of marriage or other obligations. Bede Jarrett et al., “Third Orders,” in The Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. 14 (New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912),www.newadvent.org/cathen/14637b.htm .

1 0. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 56.

11 . Wilson, Italian Painting, 58.

1 2. Lionello Venturi, Pitture italiane in America, vol. 1 (Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1931); Venturi, Lionello. Italian Paintings in America, vol. 1 ( New York: E. Weyhe and Milan: U. Hoepli, 1933).

1 3. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 53.

1 4. Federico Zeri, “Un’ipotesi sui rapporti tra Allegretto Nuzi e Francescuccio Ghissi,” Antichità viva 14, no. 5 (1975): 51.

15. Wilson, Italian Paintings, 63.

Saints and Angels

Arts Council of Great Britain. More than a Glance: An Arts Council Exhibition Showing at Sheffield, Graves Art Gallery, 4 October to 2 November 1980, Cheltenham, Cheltenham Art Gallery and Museum, 8 November to 6 December 1980, Swansea, Glynn Vivian Art Gallery and Museum, 13 December to 24 January 1981, Southampton, Southampton Art Gallery, 7 February to 8 March 1981, Wakefield, the Elizabethan Exhibition Gallery, 14 March to 19 April 1981. London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1980.

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932.

Berenson, Bernard. The Italian Painters of the Renaissance, vol. 1. London: Phaidon, 1968.

Berenson, Bernard, and Emilio Cecchi. Pitture italiane del Rinascimento: catalogo dei principali artisti e delle loro opere con un indice dei luoghi. Milan: U. Hoepli, 1936.

Coletti, Luigi. I primitivi: I senesi e i giotteschi. Novara: Istituto geografico De Agostini, 1941–47.

Davies, Martin and Dillian Gordon. The National Gallery Catalogues: The Early Italian Schools before 1400, revised by Dillian Gordon. London: National Gallery Publications, 1988.

Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1972.

Lusanna, Enrica Neri. In Duecento e il Trecento, edited by Enrico Castelnuovo, et. al. Milan: Electa, 1986.

Marabottini, Alessandro. “Allegretto Nuzi.” Rivista d’arte, ser. 3: 2, no. 27, (1952): 23–53.

Offner, Richard. “The Straus Collection Goes to Texas.” Art News 44, no. 7 (May 15–31, 1945): 16–23.

Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. New York: The Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1930–58, vol. 3: 5 (1947).

Schrader, Jack. In The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston: A Guide to the Collection. Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1981, 23, cat. 40.

Skaug, Erling S. Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico, vol. 1. Oslo: IIC Nordic Group, The Norwegian section, 1994.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Catalogue of the Edith A. and Percy S. Straus Collection Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1945.

Van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting, vol. 3. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1924.

Van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting, vol. 5. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1925.

Venturi, Lionello. Pitture italiane in America, vol. 1. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1931.

Venturi, Lionello. Italian Paintings in America, vol. 1. New York: E. Weyhe and Milan: U. Hoepli, 1933.

Zeri, Federico. “Un’ipotesi sui rapporti tra Allegretto Nuzi e Francescuccio Ghissi,” Antichità viva 14, no. 5 (1975): 3–7, figs. 3, 4.

Wilson, Carolyn C. Italian Paintings, XIV–XVI Centuries, in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in association with Rice University Press and Merrell Holberton, 1996.

Comparative Images

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has made every effort to contact all copyright holders for images and objects reproduced in this online catalogue. If proper acknowledgment has not been made, please contact the Museum.