Tea and Coffee Piazza

In 1979 the Italian design company Alessi invited prominent architects to participate in an experimental project to design a tea and coffee piazza. The idea for the project was devised by famed architect and designer Alessandro Mendini, who was artistic director of Alessi at the time, but the impetus originated with Alessi’s president, Alberto Alessi. He envisioned the company as an “applied arts research laboratory,” rather than a traditional factory, and sought to marry mass production with fine craftsmanship.1 The Tea and Coffee Piazza project participants were instructed to reevaluate the prototypical tea and coffee service and consider its architectural qualities. Within this brief, the participants were given complete freedom to design and were actively encouraged to experiment. Alessi intended for the designs to be mass produced but also offered the option to create limited-production handcrafted designs. Although many of the architects set out to design a tea and coffee piazza that could be mass manufactured, the final designs were too complex for factory production, so they were ultimately handcrafted in silver in limited editions of ninety-nine. This innovative project influenced a wave of new design as competitors responded to Alessi’s experiment with their own projects and architects became more frequently employed as product designers.2

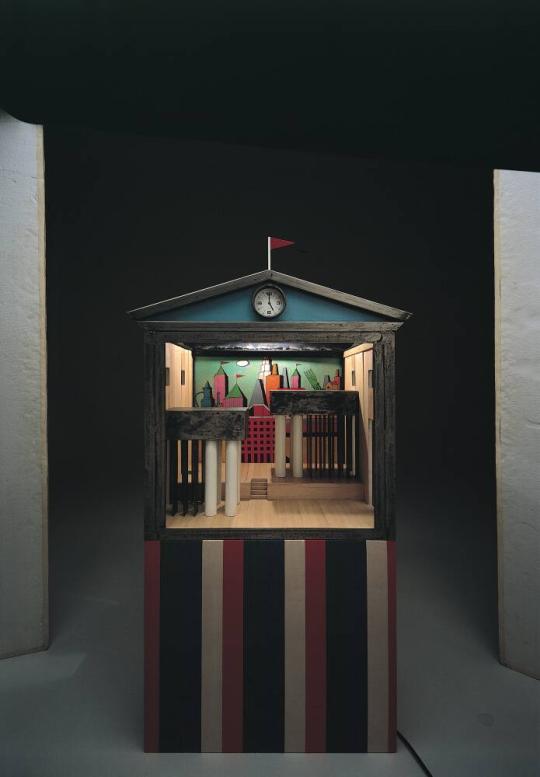

One of the participants in Alessi’s experimental Tea and Coffee Piazza project was the Italian architect and theoretician Aldo Rossi. The project was perfect for Rossi, who had already been grappling with concepts of scale and reimagining household objects as a form of domestic architecture.3 Rossi’s tea and coffee service is housed within a glass case. Its simple structure of four walls and a gabled roof demonstrates Rossi’s persistent interest in classical architecture. The case is surmounted by a pennant flag and a clock face set in the center of its light-blue pediment. The design closely relates to Rossi’s Teatrino scientifico (Little Scientific Theater), which he worked on one year prior to joining the Alessi project (fig. 45.1). Rossi described the Teatrino scientifico as “an object somewhere between a machine, a theater, and a toy: it represents the theatrical form par excellence, in its most basic design, creating a place for the scenery and action as well as for memory.”4 He viewed architecture as the theatrical backdrop upon which urban life plays out and used the Teatrino scientifico to experiment with concepts in miniature. Rossi’s Tea and Coffee Piazza embodies similar ideas. The glass case transforms into a theater, and the pieces of the service become players who perform the acts and social rituals of serving tea and coffee. The prominent place of the clock within the design signals the significance of time to Rossi’s theoretical understanding of architecture. In Teatrino scientifico, the clock is nonfunctional, calling attention to the fact that time in the theater does not abide by the same rules as our common understanding of time.5 Rossi was one of the leading proponents of Postmodernism and is renowned for his rejection of functionalism and the International Style. Many consider him to be the most influential architect of the second half of the twentieth century. Rossi was awarded the Pritzker Prize for architecture in 1990 and the Thomas Jefferson Medal in Public Architecture from the American Institute of Architects in 1991. —Sarah Marie Horne

Notes

1. Alberto Alessi as quoted in Fay Sweet, Alessi: Art and Poetry (London: Thames and Hudson, 1998), 7.

2. Thirteen architects were invited by Alessi, but only ten accepted the invitation and completed the project. The Tea and Coffee Piazza designers were Alessandro Mendini, Robert Venturi, Kazuma Yamashita, Charles Jencks, Aldo Rossi, Paolo Portoghesi, Michael Graves, Oscar Tusquets, Hans Hollein, Stanley Tigerman, and Richard Meier. Alberto Alessi, Alessi: The Design Factory (London: Academy Editions, 1994), 38–39; Alberto Alessi, The Dream Factory: Alessi since 1921 (New York: Rizzoli, 2017), 64–71; Sweet, Alessi, 24–28.

3. For an example, see Architettura domestica con monumento, 1974, pen and colored pencils on paper, private collection, as reproduced in Chiara Spangaro, Aldo Rossi: Design, Catalogue Raisonné, 1980–1997 (Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2022), 16.

4. As quoted in Spangaro, Aldo Rossi, 19; quoted from A. Ferlenga, ed., Aldo Rossi: Tutte le opera (Milan: Electa, 1999), 756.

Comparative Images

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has made every effort to contact all copyright holders for images and objects reproduced in this online catalogue. If proper acknowledgment has not been made, please contact the Museum.