First premiering in 1882, Parsifal was the final opera written by the famous composer Richard Wagner. The story of Parsifal is related to the legends of King Arthur and the quest for the Holy Grail. Wagner created the opera specifically to fit the unique acoustics of the Festspielhaus in Bayreuth, Germany, which he designed with the architect Gottfried Semper. The design of the Festspielhaus sought to eliminate any distractions or barriers between the audience and the performance to create a fully immersive and captivating experience. In part, this was achieved by hiding the orchestra beneath the theater, which allowed direct visual access to the action on stage. The audience’s inability to see the source of the music in the theater also contributed to the mystical atmosphere of the performance. In addition, the seating of the audience was leveled to eliminate class distinctions within the theater. This silently communicated the importance of the stage as the site of the audience’s focus rather than their fellow attendees.1 These environmental conditions prescribed the audience’s experience of Parsifal. Therefore, Wagner demanded that it only be performed at the Festspielhaus to ensure the integrity of this architecturally specific composition. In accordance with his wishes, the opera was not seen outside of Bayreuth, with few exceptions, until 1914, when the ban was finally lifted and performances appeared in more than forty cities.

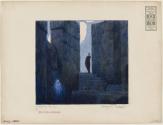

These three watercolors are scenic designs created by Heinrich Lefler for a performance of Parsifal held at the opera house in Frankfurt, Germany, in January of 1914, one of the first productions held outside of Bayreuth. Lefler designed all of the settings and costumes for the Frankfurt performance. Contemporary reviews discussed the difficultly of re-creating Wagner’s opera but praised Lefler for his fantastical use of color, clever lighting techniques, and the mesmerizing environments achieved by his scenic design, which captured something of the essence of the immersive productions in Bayreuth.2 Lefler’s scenic designs feature compositional arrangements that demonstrate the organizing design principles of the New Stagecraft. Devised in Europe, the New Stagecraft was a type of set design that prioritized line, volume, and color and utilized framing devices to make the scenery easier for the audience to visually digest.

Lefler began his career as a painter and illustrator. He was also a cofounder of the Hagenbund (1899–1938), an Austrian artist alliance, like the Vienna Secession, that rejected historicism and traditional ornament in favor of a new artistic style. However, Lefler is best known for his work with the Viennese architect and designer Joseph Urban, who was also his brother-in-law. Urban and Lefler were business partners and often worked collaboratively. Their joint projects included graphic design, illustration, scenic design, and interior design, as well as temporary architectural installations, such as the pavilions for Emperor Franz Josef I’s diamond jubilee in 1908. Their partnership ended when Urban immigrated to the United States in 1912.3 —Sarah Marie Horne

Notes

1. Lewis Kaye, “The Silenced Listener: Architectural Acoustics, the Concert Hall and the Conditions of Audience,” Leonardo Music Journal 22 (2012): 63–65, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23343812 (accessed October 16, 2023).

2. “Die Künstlerishe Inszenierung des Parsifal,” in Die Kunst XVII (Munich: F. Bruckmann, 1914), 457–64, and D. Sonne, “Wagners ‘Parsifal’ auf seiner Wanderung über die Opernbühnen des In und Auslandes,” Illustrirte Zeitung 3681, January 15, 1914, 118–20. Joseph Urban Papers, Columbia Rare Books and Manuscript Library.

3. Arnold Aronson, Derek E Ostergard, Joseph Urban, Derek E Ostergard, Matthew Wilson Smith, and Wallach Art Gallery, Architect of Dreams: The Theatrical Vision of Joseph Urban (New York: Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University, 2000), 27.