Adjustable Table Lamp Model No. T-5-G

In May 1950, the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA), New York, in partnership with Heifetz Manufacturing Company, a producer of portable lighting, announced its first Lamp Design Competition, seeking entries for the design of table and floor lamps. Rene d’Harnoncourt, the museum’s director, described the genesis of the competition: “A lively controversy on the subject of good lamps for the home was in full swing . . . set off by a remark of the architect Marcel Breuer. As the designer of the Museum’s 1949 exhibition The House in the Museum’s Garden, he claimed that he had not found on the market one single satisfactory floor or table lamp for this house.”1 Breuer’s lament and the ensuing discussions inspired Heifetz to approach MOMA that same year about sponsoring a lamp competition, leading the two entities to join together to create a contest that would result in an exhibition, tour, and retail partnerships.

Previously, MOMA had experienced success with its International Competition for Low-Cost Furniture Design in 1948–49. The submission and jurying process established by the earlier competition was adopted with adjustments for the Lamp Design Competition. MOMA hoped that innovative but practical lamp designs that would be suitable for the small, modern American homes prevalent during the time would be submitted by both known and unknown designers. The prize winners would be exhibited at the museum, with Heifetz committing to producing up to three-quarters of the winning designs.

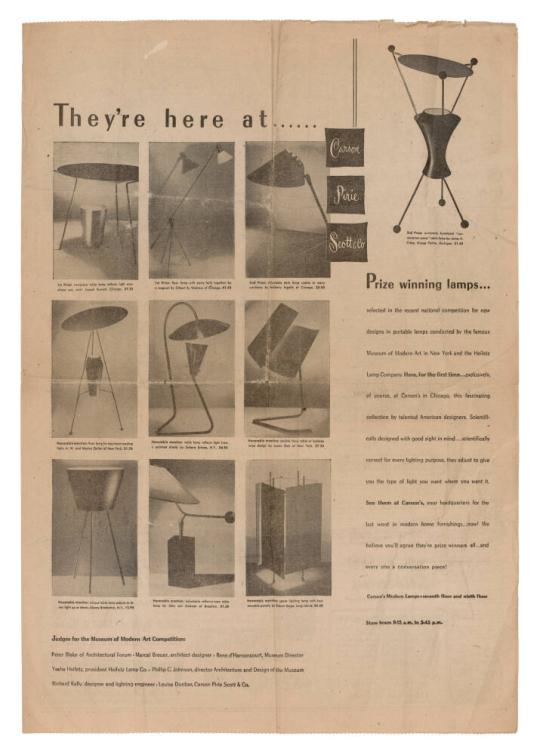

MOMA stated that it was holding the lighting competition “to encourage the design and production of good portable lamps of two types: table lamps and floor lamps. All lamps shall employ incandescent bulbs. However, there are no further restrictions concerning the materials used, so long as they prove reasonably suitable to a product of this type. While cost shall not be the decisive factor in the design . . . the competing designers shall attempt to keep the manufacturing cost within reasonable limits.”2 All designs were to be original and not previously manufactured or for sale. Ultimately, more than three thousand submissions by more than six hundred designers from forty-three states were reviewed by a jury of architecture and design luminaries that included Breuer; Philip C. Johnson, director of the department of architecture and design at MOMA; and Richard Kelly, a designer and lighting engineer. Yasha Heifetz, designer and president of Heifetz, and Louis Dunbar of Carson Pirie Scott & Co. also served as judges.

Of the fifteen lamps singled out by the jury, eight table lamps and two floor lamps were awarded prizes and placed into production. Honorable mention was awarded to Lester Geis’s T-5-G table lamp, with the jury noting that “this design offers an extremely practical solution. The two-piece shade, each part of which moves individually, allows for simultaneous light adjustment in two directions.”3 Geis, like the majority of the prize winners, was young and unknown, a fact that delighted the jury.4 Born in Chicago and having graduated with a degree in architecture from Carnegie Tech, Geis was an architect and inventor who had applied for patents for numerous industrial designs by the time he submitted his lamp design to MOMA. The museum’s press release announcing the winners of the competition also described him as the Eastern sales manager for an unnamed Chicago lighting equipment firm.5

Geis’s design spoke to the trends of the time with its linear and geometric shapes and strategic use of color, and by diffusing and directing of light through perforations and adjustable elements. The lamp’s functionality was emphasized in newspapers, magazines, and advertisements across the country. Geis’s lamp was given a retail price of $27.50, approximately three to five times the price of other table lamps from the period.

The chosen lamps and their original design presentations were exhibited in the New Lamps show at MOMA from March 28 through June 3, 1951. MOMA also organized a simultaneous presentation in April of the ten prize winners at museums nationwide, each of which was paired with sponsor and participating stores. The sponsoring stores received a ninety-day “exclusive franchise” and were mentioned in all of the publicity relating to the competition, while the participating stores were given a thirty-day exclusive in their region (fig. 21.1).6

The lamps received positive responses from consumers who saw local window and floor displays and newspaper advertisements, all of which offered some insight about how the lamps could be coordinated stylistically with customers’ existing home furniture.7 Retailers in the larger sponsoring cities reported an increase in traffic and some sales in the first weeks of the lamps’ availability.8 While these department and design stores were enthusiastic about the lamps, the lighting trade, which specialized only in lamps as opposed to other home furnishings, was less so, whether due to jealousy or other limiting perspectives regarding the style of the lamps.9

Sales, the arbiter of commercial success, were ultimately limited. It is unclear how many of each model were produced or sold, as Heifetz did not release statistics. Most likely, fewer than twenty of Geis’s lamps were produced, based on extant examples known today. —Cindi Strauss

Notes

1. Rene d’Harnoncourt, “Report of the Jury,” Museum of Modern Art Archives, MOMA Exhibitions, 473.5.

2. The Museum of Modern Art, Lamp Design Competition Entry Brochure (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1950), Hirsch Library Collection, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. I am grateful to Paul Galloway, collections manager in the department of architecture and design at the Museum of Modern Art, for providing a copy of the brochure for the Hirsch Library.

3. “Lester Geis, Honorable Mention,” Museum of Modern Art Archives, MOMA Exhibitions, 473.5.

4. D’Harnoncourt, “Report of the Jury.”

5. The Museum of Modern Art, “Prize-Winning Lamps on Exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art Go on Sale Here,” press release, March 1951.

6. Ibid.

7. “The Prize-Winners,” Retailing Daily, April 2, 1951, 15, 19.

8. Ibid.

9. Earl Lifshey, “Nothing Ventured . . . ,” Retailing Daily, Friday, May 25, 1951, cover.

Comparative Images

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has made every effort to contact all copyright holders for images and objects reproduced in this online catalogue. If proper acknowledgment has not been made, please contact the Museum.